Chronic Pain

Is Impaired Neuroplasticity Linked to Chronic Pain?

New research links chronic pain with impaired neuroplasticity of the brain.

Posted March 13, 2014

Neuroscientists have made breakthrough discoveries on how neuroplasticity varies in people with chronic pain. These studies shed new light on how the brain processes pain and could lead to better treatments for chronic pain.

Chronic pain is common throughout the world. More than 100 million Americans are believed to be affected by chronic pain. Approximately 20 percent of adults suffer moderate to severe chronic pain.

Neuroplasticity is the term used to describe the brain's ability to change structurally and functionally based on personal experience and use. One of the fundamental principles of how neuroplasticity functions is linked to the concept of synaptic pruning.

Neural pruning is based on the fact that individual connections within the brain are constantly being reconnected or reshaped, based on how much they are used and deemed important, or unnecessary. The brain likes to stay streamlined, but sometimes this process goes haywire—as may be the case with chronic pain.

The basic concept of neuroplasticity is based on the idea that, "neurons that fire together, wire together" and "neurons that fire apart, wire apart." If there are two neurons that work together and often produce an impulse simultaneously, their cortical maps will become a neural network.

This idea also works in the opposite way—neurons that do not work together or regularly produce simultaneous impulses will form different connections and stop communicating. This is the key to neuroplasticity, neural pruning and brain connectivity.

Impaired Neuroplasticity Linked to Chronic Pain

"Neuroplasticity underlies our learning and memory, making it vital during early childhood development and important for continuous learning throughout life," says Dr. Ann-Maree Vallence, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the University of Adelaide's Robinson Institute in Australia.

Dr. Vallence conducted a study on patients with chronic tension-type headache (CTTH), a common chronic pain disorder. CTTH is characterized by a dull, constant feeling of pressure or tightening that usually affects both sides of the head, occurring for 15 days or more per month. Other symptoms include poor sleep, irritability, disturbed memory and concentration and depression and anxiety.

"The mechanisms responsible for the development of chronic pain are poorly understood. While most research focuses on changes in the spinal cord, this research investigates the role of brain plasticity in the development of chronic pain." Dr. Vallence will present her findings at the March 2014 European Winter Conference on Brain Research in France.

"People living with chronic headache and other forms of chronic pain may experience reduced quality of life, as the pain often prevents them from working, amongst other things. It is therefore imperative that we understand the causes of chronic pain, not just attempt to treat the symptoms with medication," Dr. Vallence says.

In this study, participants undertook a motor training task consisting of moving their thumb as quickly as possible in a specific direction. The change in performance (or learning) on the task was tracked by recording how quickly subjects moved their thumb. A non-invasive brain stimulation technique was also used to obtain a measure of the participants' neuroplasticity.

"Typically, when individuals undertake a motor training task such as this, their performance improves over time and this is linked with a neuroplastic change in the brain," Dr. Vallence says. "The people with no history of chronic pain got better at the task with training, and we observed an associated neuroplastic change in their brains. However, our chronic headache patients did not get better at the task and there were no associated changes in the brain, suggesting impaired neuroplasticity.”

"These results provide a novel and important insight into the cause of chronic pain, and could eventually help in the development of a more targeted treatment for CTTH and other chronic pain conditions," she concluded.

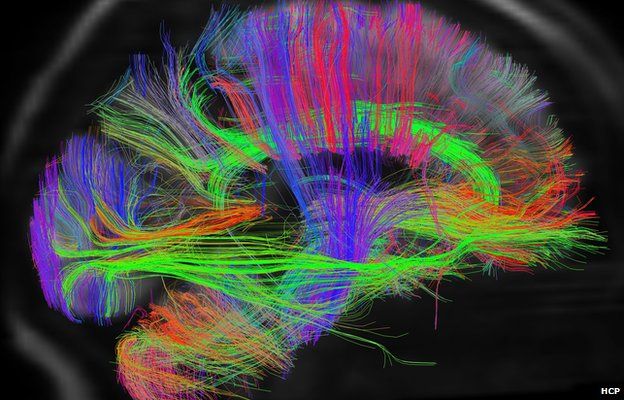

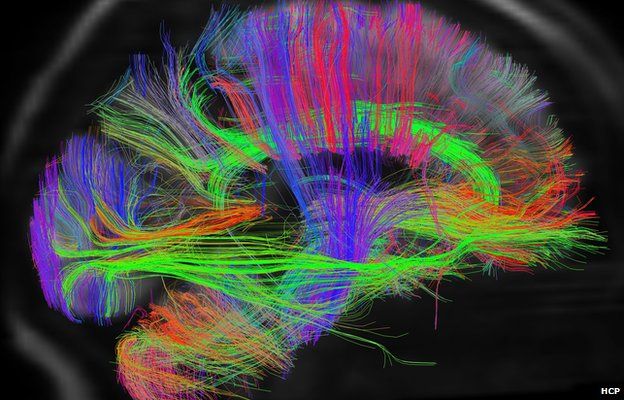

Altered Connectivity of the Default Mode Network Linked to Chronic Pain

In another recent study on neuroplasticity and chronic pain, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston focused on a specific network of brain regions called the Default Mode Network (DMN). The researchers found that the DMN exhibited dramatic neuroplastic changes in neural connectivity when a patient with chronic pain moved in a way that increased back pain. The study appears in the January 2013 print edition of the journal Pain.

Brain connectivity in the DMN linked to chronic pain.

During acute pain regions within the DMN (such as the medial prefrontal cortex) became less connected with the rest of the network, whereas regions outside the network (such as the insula) became more strongly connected with this network. Some of these observations have been noted in previous studies of fibromyalgia patients, which suggests these changes in brain connectivity might reflect a general feature of chronic pain.

I wrote about the role of the insula in both physical and social pain in a recent Psychology Today blog post titled, "The Neuroscience of Social Pain," if you'd like to read more on this topic.

"We showed that specific brain patterns appear to track the severity of pain reported by patients, and can predict who is more likely to experience a worsening of chronic back pain while performing maneuvers designed to induce pain," said Marco Loggia, PhD, the lead author of the study and a researcher in the Pain Management Center at BWH and the Department of Radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Loggia said, “While we need to be cautious in the interpretation of our results, this has the potential to be an exciting discovery for anyone who suffers from chronic pain. We don't really understand exactly what is behind all this, any interpretation is pure speculation at this point, but what we see is that the pain exacerbation induces a temporary disruption in the connectivity pattern."

While the findings suggest that the brain can compensate and adapt to pain, it is not clear whether overall brain function might be compromised in some way.

Dr. Loggia concluded, "We cannot make too many inferences based on a single study but one possibility is that the increased connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and DMN that we see at baseline might be some compensatory mechanism, as if maybe the patients raise their baseline connectivity in order to somehow brace for the next pain episode which, as our data suggest, will disrupt the connectivity."

Conclusion: More Research on Neuroplasticity and Chronic Pain Is Needed

The fact that the brain's response to pain can be objectively identified and quantified using brain imaging could lead to improved monitoring and better treatments from chronic pain in the future. Hopefully, these types of findings will lead to more clinic trials and research.

Catherine Bushnell, PhD, president of the Canadian Pain Society in Montreal, Quebec, commented, "This exciting study adds to the growing literature indicating that chronic pain alters the brain. Showing changes in connectivity between brain regions important for mood and cognitive function could help explain why pain patients frequently develop anxiety disorders and have problems with memory and decision making."

Bushnell concludes that, “studies of brain function and structure in a wide variety of chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, arthritis, and neuropathic pain, are now showing changes in the brain suggesting that chronic pain is more than just a symptom. Because of these types of studies, many doctors are beginning to think of chronic pain as a disease in itself."

If you’d like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Eight Habits that Improve Cognitive Function”

- “Chronic Stress Can Alter Brain Structure and Connectivity”

- "The Neuroscience of Social Pain"

- "The Secret to Better Decision Making"

- "Neuroscientists Discover How Practice Makes Perfect”

- "The Size and Connectivity of the Amygdala Predicts Anxiety”

- “The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure”

- ”How Does Meditation Reduce Anxiety At a Neural Level?”

- "What Is the Connectome Project? Why Should You Care?"

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.