Altruism

The Evolutionary Biology of Altruism

Compassion, cooperation, and community are key to our survival.

Posted December 25, 2012

Would you rather give than receive? Do you believe that anyone ever acts with pure, selfless altruism? Do humans always “give” to “get” a little something in return whether it be an actual ‘tit-for-tat’ reward, or a warm feeling of having been magnanimous?

I have been thinking a lot about these questions this Christmas Day and filtering my observations through the lens of all the exciting scientific research about the evolutionary biology of altruism reported this year.

Practicing love and kindness to others actually benefits you, your family, your social network, and your community at large. Even if you are feeling ‘selfish’, behaving selflessly may be the wisest ‘self-serving’ thing to do. If you want to have a competitive advantage in the long-run, science confirms that altruism, compassion and cooperation are all key ingredients for your success.

2012 was a hallmark year for scientific progress in understanding the evolutionary biology behind altruism, compassion and the importance of community. Neuroscientists have made huge progress in understanding our “social brain” which consists of structures and circuits that help us understand one anothers' intentions, beliefs, desires, and how to behave appropriately.

In this entry, I will connect the dots between all of this research and create a timeline that will hopefully be a resource as we try to find ways to create more loving-kindness in our society and less violence and bloodshed.

Christmas Day 2012

I woke up early this Christmas morning. While I was waiting for the water to boil I noticed a book called “Essays of E.B. White” on the kitchen table and started flipping through it. I stumbled on an essay called Unity which E.B. White wrote in 1960. I had been reading a lot of science articles about the evolutionary importance of community, cooperation, and empathy lately and the words from his essay hit home:

“Most people think of peace as a state of Nothing Bad Happening, or Nothing Much Happening. Yet if peace is to overtake us and make us the gift of serenity and well being, it will have to be the state of Something Good Happening. What is this good thing? I think it is the evolution of community.”

My mom has a December 24th tradition of spending the day with her good friend and next-door-neighbor at "The Haven” which is a local food bank. They distribute food to individuals and families in the community who are in need. Last night she came home with heartwarming (and heartbreaking) stories of various people who had come to the food bank that day. My mom doesn’t consider working at The Haven “volunteering”, or a sacrifice. Not because she’s saintly, or more altruistic than most....My mom realized a long time ago that it made her feel better around the holidays to connect with other people in the community from all walks of life than to sit at home all day by the fire with family, indulging. Scientists continue to confirm that her empirical findings and intuitions can be backed up in a laboratory or clinical studies.

The Evolutionary Biology of Altruism

In 1975, Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson published Sociobiology, which was viewed by most people at the time to be the most important evolutionary theory since On the Origin of Species. Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection and the “survival of the fittest” implied a machiavellian world in which individuals clawed their way to the top. Wilson offered a new perspective which was that certain types of social behaviors— including altruism—are often genetically programmed into a species to help them survive.

In the context of Darwin’s theory of 'every man for himself' Natural Selection, this kind of selflessness or altruism did not compute. E.O. Wilson resolved the paradox with a ‘one for all and all for one’ theory called “kin selection”.

According to the kin selection theory, altruistic individuals would prevail because the genes that they shared with kin would be passed on. Since the whole clan is included in the genetic victory of a few, the phenomenon of beneficial altruism came to be known as “inclusive fitness.” By the 1990s this had become a core concept of biology, sociology, even pop psychology.

As a gay person who came out in the 1980s, I always felt a very close ‘familial’ connection with my peers. The LGBT community was my clan and I was loyal to any member of my group who had the courage to come out. In the mid-80s I wrote a college paper about Sociobiology and Homosexuality. I always had a problem with E.O. Wilson's ideas of kin selection and altruism based on genetics. This was reconfirmed when I joined ACT-UP in the late 80s and witnessed fierce altruism in action with no genetic ties as we formed a coalition and took to the streets.

In 2010, E.O. Wilson announced that he no longer endorsed the kin selection theory he had developed for decades. This caused a big stir in evolutionary biologist circles. He acknowledged that according to kin theory, that altruism arises when the "giver" has a genetic stake in the game. But after a mathematical assessment of the natural world, Wilson and his colleagues at Harvard University decided that altruism evolved for the good of the community rather than for the good of individual genes. As Wilson put it, cooperating groups dominate groups who do not cooperate.

Wilson’s new research indicates that self-sacrifice to protect a relation’s genes does not drive evolution. In human terms, family is not so important after all; altruism emerges to protect social groups whether they are kin or not. I think this is important for all of us to remember as we try to unite and bridge our differences. One caveat here, sticking too much with the group can be a bad thing, too...

When people compete against one other they are selfish, but when group selection becomes important, then the altruism characteristic of human societies kicks in, Wilson says. “We may be the only species intelligent enough to strike a balance between individual and group-level selection, but we are far from perfect at it. The conflict between the different levels may produce the great dramas of our species: the alliances, the love affairs, and the wars.”

Scientists confirm that we must cooperate to survive.

In November of 2012, Wilson’s theory was backed up by Michael Tomasello and researchers in the Department of Developmental and Comparative Psychology at the The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Their research, published by Current Anthropology offers an explanation why humans are much more inclined to cooperate than are their closest evolutionary relatives.

The prevailing wisdom about why this is true has long been focused on the idea of altruism: we go out of our way to do nice things for other people, sometimes even sacrificing personal success for the good of others. Modern theories of cooperative behavior suggest that acting selflessly in the moment provides a selective advantage to the altruist in the form of some kind of return benefit.

The authors of the study argue that humans developed cooperative skills because it was in their mutual interest to work well with others—practical circumstances often forced them to cooperate with others to obtain food. In other words, altruism isn't the reason we cooperate; we must cooperate in order to survive, and we are altruistic to others because we need them for our survival.

Previous theories located the origin of cooperation in either small group settings or large, sophisticated societies. Based on results from cognitive and psychological experiments and research on human development, this study provides a comprehensive account of the evolution of cooperation as a two-step process, which begins in small hunter-gatherer groups and becomes more complex and culturally inscribed in larger societies later on.

The authors premise their theory of mutualistic cooperation on the principle of interdependence. They speculate that at some point in our evolution, it became necessary for humans to forage together, which meant that each individual had a direct stake in the welfare of his or her partners. Individuals who were able to coordinate well with their fellow foragers, and would pull their weight in the group, were more likely to succeed.

In this context of interdependence, humans evolved special cooperative abilities that other apes do not possess, including dividing the spoils fairly, communicating goals and strategies, and understanding one's role in the joint activity as equivalent to another's.

As societies grew in size and complexity, their members became even more dependent on one another. In what the authors of this study define as a second evolutionary step, these collaborative skills and impulses were developed on a larger scale as humans faced competition from other groups. People became more "group-minded," identifying with others in their society even if they did not know them personally. This new sense of belonging brought about cultural conventions, norms, and institutions that incentivized and structured feelings of social responsibility.

Our "Social Brain" may have a specific region hard-wired to share.

Research appearing in the December 24, 2012 journal Nature Neuroscience found that although a monkey would probably never agree that it is better to give than to receive, they do get some reward in a specific brain region from giving to another monkey.

The experiment consisted of a task in which rhesus macaques had control over whether they, or another monkey, would receive a squirt of fruit juice. Three distinct areas of the brain were found to be involved in weighing benefits to oneself against benefits to the other, according to a new research study by the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences and the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience. This research, led by Michael Platt, is another piece of the puzzle as neuroscientists search for the roots of charity, altruism and other social behaviors in our species and others.

There have been two schools of thought about how the social reward system is set up, Platt said. "One holds that there is generic circuitry for rewards that has been adapted to our social behavior because it helped humans and other social animals like monkeys thrive. Another school holds that social behavior is so important to humans and other highly social animals like monkeys that there may be some special circuits for it." This research is part of a new field of study into what neuroscientists are calling the Social Brain.

Using a computer screen to allocate juice rewards, the monkeys preferred to reward themselves first and foremost. But, they also chose to reward the other monkey if it meant no juice for either of them. Also, monkeys were more likely to give the reward to a monkey they knew over one they didn't. Interestingly, they preferred to give juice to lower status than higher status monkeys. And lastly, they had almost no interest in giving the juice to an inanimate object.

The team used sensitive electrodes to detect the activity of individual neurons as the animals weighed different scenarios, such as whether to reward themselves, the other monkey, or nobody at all. Three areas of the brain were seen to weigh the problem differently depending on the social context of the reward. When given the option either to drink juice from a tube themselves or to give the juice away to a neighbor, the test monkeys would mostly keep the drink. But when the choice was between giving the juice to the neighbor or neither monkey receiving it, the choosing monkey would frequently opt to give the drink to the other monkey.

Through the development of the specific part of the brain that experiences the reward of others, social decisions and empathy-like processes may have been favored during evolution in primates to allow altruistic behaviour. “This may have evolved originally to promote being nice to family, since they share genes, and later friends, for reciprocal benefits,” says Michael Platt.

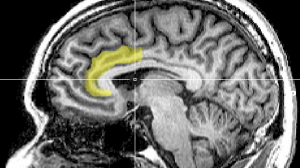

Anterior cingulate gyrate (ACCg) in yellow

His team found that in two out of the three brain areas being recorded, appeared "divorced from social context," Platt said. But a third area, the anterior cingulate gyrus (ACCg), seemed to "care a lot about what happened to the other monkey," Platt said. ACCg has emerged as an important nexus for the computation of shared experience and social reward.

The authors suggest that the intricate balance between the signalling of neurons in these three brain regions may be crucial for normal social behavior in humans, and that disruption may contribute to various psychiatric conditions, including autistic spectrum disorders.

“This is the first time that we have had quite such a complete picture of the neuronal activity underlying a key aspect of social cognition. It is definitely a major achievement,” says Matthew Rushworth, a neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK.

Neuroscientists have discovered the seat of human compassion.

In September of 2012, an international team led by researchers at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York published research in the journal Brain declaring that: “one area of the brain, called the anterior insular cortex, is the activity center of human empathy, whereas other areas of the brain are not.” The insula is a hidden region folded and tucked away deep in the brain. It is an island within the cortex.

This most recent study firmly establishes that the anterior insular cortex is where feelings of empathy originate. "Now that we know the specific brain mechanisms associated with empathy, we can translate these findings into disease categories and learn why these empathic responses are deficient in neuropsychiatric illnesses, such as autism," said Patrick R. Hof, MD, a co-author of the study. "This will help direct neuropathologic investigations aiming to define the specific abnormalities in identifiable neuronal circuits in these conditions, bringing us one step closer to developing better models and eventually preventive or protective strategies."

According to Dr. Gu, another researcher on this study, this provides the first evidence suggesting that the empathy deficits in patients with brain damage to the anterior insular cortex are surprisingly similar to the empathy deficits found in several psychiatric diseases, including autism spectrum disorders, borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, and conduct disorders, suggesting potentially common neural deficits in those psychiatric populations.

"Our findings provide strong evidence that empathy is mediated in a specific area of the brain," said Dr. Gu, who now works at University College London. "The findings have implications for a wide range of neuropsychiatric illnesses, such as autism and some forms of dementia, which are characterized by prominent deficits in higher-level social functioning."

This study suggests that behavioral and cognitive therapies can be developed to compensate for deficits in the anterior insular cortex and its related functions such as empathy in patients. These findings can also inform future research evaluating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying complex social functions in the anterior insular cortex and develop possible pharmacological treatments for patients.

Conclusion

We’re all in this together. We have not evolved for millennia to be isolated behind digital screens, connected only via text message and social media, or to grow up playing violent video games in windowless basements.

Science proves that our genes and our brains have evolved to be compassionate, to cooperate, and to foster community. This is common sense. Hopefully, the science presented here reinforces what we already know intuitively. Being altruistic and kind to one another benefits us all.