Transgender

In the Early Morning Rain

A transgender woman holds her life in her hands, and decides to live.

Posted February 19, 2013

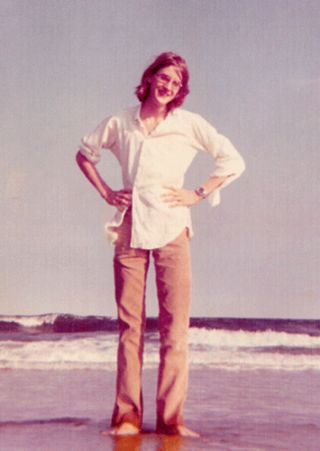

Jennifer Boylan, during her young years as James.

When I was young there was a time when I figured, the hell with it. I’d never even said the word transgender out loud. I couldn’t imagine saying it, ever. I mean, please.

So instead, one day a few years after I got out of college, I loaded all my things into the Volkswagen and started driving. I wasn’t sure where I was going, but I knew I wanted to get away from the Maryland spring, with its cherry blossoms and its bursting tulips and all its bullshit. I figured I’d keep driving father and farther north until there weren’t any people. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do then, but I was certain something would occur to me that would end this transgender business once and for all.

I set my sights on Nova Scotia. I drove to Maine and took a ferry out of Bar Harbor. I drove onto the S.S. Bluenose and stood on the deck and watched America drift away behind me, which as far as I was concerned was just fine.

There was someone walking around in a rabbit costume on the ship. He’d pose with you and they’d snap your picture and an hour or so later you could purchase the photo of yourself with the rabbit as a memento of your trip to Nova Scotia. I purchased mine. It showed a sad looking boy——I think that’s a boy—-- with long hair reading a book of poetry as a motheaten rabbit bends over him.

In Nova Scotia I drove the car east and north for a few days. When dusk came, I’d eat in a diner, and then I’d sleep either in the car or in a small tent that I had in the back. There were scattered patches of snow up there, even in May. I kept going north until I got to Cape Breton, which is about as far away as you can get from Baltimore and still be on dry land.

In Cape Breton I hiked around the cliffs, looked at the ocean. At night I lay in my sleeping bag by the sea as breezes shook the tent. I wrote in my journal, or read the poetry of Robert Frost, or grazed around in the Modern Library’s Great Tales of Horror and the Supernatural. I read one up there called Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.

The author in 2008, twenty years after standing at the edge of a cliff in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

In the car I listened to the Warlocks sing In the Early Morning Rain on the tape deck. I thought about this girl I knew, Grace Finney. I thought about my parents. I thought about the clear, inescapable fact that I was female in spirit and how, in order to be whole, I would have to give up on every dream I’d had, save one.

I stayed in a motel one night that was officially closed for the season, but which the operator let me stay in for half price. I opened my suitcase and put on my bra and some jeans and a blue knit top. I combed my hair out and looked in the mirror and saw a perfectly normal looking young woman. This is so wrong? I said to myself in the mirror. This is the cause of all the trouble?

I thought about settling in one of the little villages around here, just starting life over as a woman. I’d tell everyone I was Canadian.

Then I lay on my back and sobbed. Nobody would ever believe I was Canadian.

The next morning I climbed a mountain at the far northern edge of Cape Breton Island. I climbed up to the top, trying to clear my head, but it wouldn’t clear. I kept going up and up, past the tree line, past the shrub line, until at last there was just moss.

There I stood, looking out at the cold ocean, a thousand miles below me, totally cut off from the world.

A fierce wind blew in from the Atlantic. I leaned into it. I saw the waves crashing against the cliff below. I stood right at the edge. My heart pounded.

I leaned over the edge of the precipice, but the gale blowing into my body kept me from falling. When the wind died down, I’d start to fall, then it would blow me back up again. I played a little game with the wind, leaning a little further over the edge each time.

Then I leaned off the edge of the cliff at a sharp angle, my arms held outward like wings, my body sustained only by the fierce wind, and I thought, well all right. Is this what you came here to do?

Let’s do it then.

Then a huge blast of wind blew me backwards and I landed on the moss. It was soft. I stared straight up at the blue sky, and I felt a presence.

Are you all right, Son? said the voice. You’re going to be all right. You’re going to be all right.

Looking back now, I am still not sure whose voice that was. My guardian angel? The ghost of my father? I don’t know. Does it really change things all that much, to give a name to the spirits that are watching out for us?

Still, from this vantage point—over twenty-five years later –my heart tells me that was the voice of my future self, the woman that I eventually became, a woman who, all these years later, looks more or less like the one I saw in the mirror in the motel. Looking back on the sad, desperate young man I was, I am trying to tell him something. It will get better. It will not always hurt the way it hurts now. The thing that right now you feel is your greatest curse will someday, against all odds, turn out to be your greatest gift.

It’s hard to be gay, or lesbian. To be trans can be even harder. There have been plenty of times when I’ve lost hope.

But in the years since I heard that voice—Are you all right, Son? You’re going to be all right—I’ve found, to my surprise, that most people have treated me with love. Some of the people I most expected to lose, when I came out as trans, turned out to be loving, and compassionate, and kind.

I can’t tell you how to get here from there. You have to figure that out for yourself. But I do know that instead of going off that cliff, I walked back down the mountain that morning and instead began the long, long journey toward home.

(This essay appeared in different form, in She's Not There: a Life in Two Genders, published by Broadway/Random House in 2003; an updated, 10th anniversary edition of the memoir is forthcoming in April of 2013, and will feature a new chapter by the author, bringing the story up to date, along with an epilogue by the author's wife Deedie, who is called "Grace" in the book. Another version of this story was published in It Gets Better, edited by Dan Savage and )