Relationships

What Do People Really Think of Alternative Relationships?

New studies open a window onto perceptions of a growing trend.

Posted June 17, 2014

bokan/Shutterstock

The last few years have seen a marked increase in media coverage of openly non-monogamous relationships. From swinging, to polyamory, to monogamish arrangements, more and more people are becoming aware of the alternatives to complete monogamy.

But has this awareness translated into greater acceptance? Or are openly nonmonogamous relationships, and the people who engage in them, still perceived as "worse" than their monogamous counterparts?

A series of recent studies by a research team at the University of Michigan, now published in Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, suggests that, in the minds of most people, consensual nonmonogamy (CNM) remains far inferior to monogamy.

In an initial study, psychologists Terri Conley, Amy C. Moors, and their colleagues recruited 1,101 participants (mean age 24 years, 65 percent female, 28 percent non-white, and 31 percent college students) for an online study by posting links to the survey on volunteer sections of classified advertisement sites like craigslist.org. Half the sample was randomly assigned to read a description of monogamy (“Two people agree to have a sexual and romantic relationship only with one another”) and the other half a description of consensual nonmonogamy (“People agree to have sexual and/or romantic relationships with more than one person, and the partners involved are aware that multiple relationships are occurring”). Then, participants rated the relationship they read about based on the extent to which they believed it provided various relationship benefits.

As you can see from the graph, monogamy was perceived as better than consensual nonmonogamy on 20 out of 22 measures of perceived relationship benefits—everything from sexual/physical health to closeness/trust/romance to financial benefits and moral superiority. These differences were not only statistically significant, they were large—larger than most effects ever seen in psychological studies. Just look at the "prevents STIs" difference: It is full four points on a seven-point scale. What's more, CNM was rated as far below the mid-point of the scale on most relationship benefits. The only two benefits more often credited to CNM than to monogamy were preventing boredom and allowing independence.

Funnily enough, in a phenomenon known as the “halo effect,” this negativity toward nonmonogamy extended to traits and behaviors that have nothing to do with relationships. For example, monogamous relationships were perceived to be better at encouraging paying taxes on time, daily dog walking, taking multivitamins, and daily teeth flossing.

Because they had such a big sample, the researchers could test whether these perceptions were shared by various subpopulations. The findings were virtually identical for college students and noncollege adults, for both women and men, across all ethnic groups—and for heterosexual, lesbian, gay, and bisexual participants. All agreed that monogamy was better. Perhaps more surprisingly, the findings were similar even for the 4.3 percent of the sample who reported currently being in a CNM relationship! Even nonmonogamous people themselves actually supported the institution of monogamy—something akin to internalized homophobia sometimes experienced among LGB people.

In a second sample, the team investigated whether these negative views would extend to specific monogamous or CNM romantic relationships, rather than the general category of (non)monogamy. So they again recruited people through Facebook and Craigslist—a smaller and older sample this time (132 participants with a mean age of 35)—and had them read a description of a couple (Sara and Dan) who’ve been together for five years, enjoy each other’s company, and hope to get married some day. But one half of participants also read that Sara and Dan “have been monogamous for their entire relationship, are finding themselves to be happy with this arrangement, and plan to continue to be monogamous," while the other half read that “they were monogamous for the first four years of their relationship, then, a year ago, both mutually agreed that it would be okay if they have other sexual partners. For about a year, they have been engaging in relationships with other partners. They are finding themselves happy with this arrangement and plan to continue to be nonmonogamous.” The participants then rated Dan and Sara’s relationship on a number of characteristics.

Similar to the general category of consensual nonmonogamy, this specific nonmonogamous relationship was rated as worse for sexual health, moral acceptability, relationship quality, loneliness, sexual satisfaction, and arbitrary benefits.

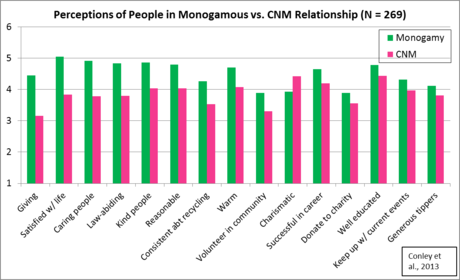

A fourth online sample (269 people with a mean age of 34) confirmed that this negativity extends to other relationship benefits not assessed previously, including having shared interests, good communication, being equals, or arguing rarely. As the graph below illustrates, the perception also extends to individual personality characteristics that shouldn’t be related to relational processes, from being generous and caring, to being successful and educated, to being law abiding and charitable. The only perceived redeeming characteristic of nonmonogamous people was being more charismatic.

You may already be convinced, but the researchers didn’t stop here: In a follow-up paper, they further clarified the reach of nonmonogamy stigma. Across three large online samples (ranging from 460 to 720 participants each) recruited using social media, CNM relationships and people were rated worse than monogamous ones...:

- When the CNM couple had been nonmonogamous right from the beginning (as opposed to starting monogamous then opening up four years later, as in the initial study);

- When people rated Dan and Sara (i.e., the male and the female target of the couple) individually. Except for sexual satisfaction, nonmonogamous men were not perceived as any better—or worse—than nonmonogamous women, but both were viewed more negatively than a monogamous man or woman, respectively.

- When people evaluated lesbian or gay couples (as opposed to a heterosexual couple). As it happens, CNM gay and lesbian couples were viewed slightly more positively than CNM heterosexual couples, but both were viewed more negatively than a monogamous couple of their respective sexual orientation.

This impressive body of work undoubtedly points to the conclusion that even among relatively young, social media-connected people, stigma against consensual nonmonogamy and the people who engage in it is strong, robust, and pervasive, stretching across virtually all personality and relationship characteristics, and all demographic groups (including nonmonogamous people themselves).

If nonmonogamous lifestyles are here to stay, we have a long way to go to make these people feel welcome.

Have a casual sex story to share with the world? Or want to read other people's hookup experiences? That's what The Casual Sex Project and @CasualSexProj are for.

Follow me on Twitter @DrZhana for daily updates on the latest in sex research, check out my website or my Facebook page for more information about me, or sign up for my monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all my sex research-related activities.

References

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2013). The fewer the merrier?: Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13, 1-30. doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2012.01286.x

Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., Rubin, J. D. , & Conley, T. D. (2013). Stigma toward individuals engaged in consensual nonmonogamy: Robust and worthy of additional research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13, 52-69. doi:10.1111/asap.12020