Cognition

The Rise of Simplistic Language

Bilingualism is changing the world, and it's changing language too.

Posted August 20, 2014

Language structure and change are marvelous things. Consider the origins of the English word 'have'. Where could such a word have come from? As it turns out, this rather abstract verb comes from the Proto-Indo-European root 'kap', which meant 'to seize'. You can still see some remnants of this in words like 'capture' and 'captive'. Even more interesting is the fact that, historically, 'k' and 'p' sounds are notorious for changing into 'h' and 'f' sounds—like the change from 'pater' to 'father' and from 'nacht' to 'night'.

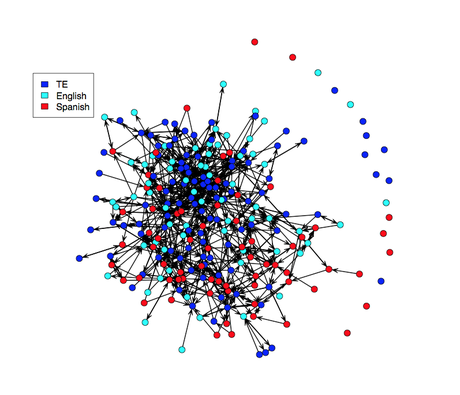

A semantic network of words form a Spanish-English bilingual. TEs are translational equivalents

Languages are changing all the time and they even change despite us. Samuel Johnson authored A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755 in an effort to iron out things like spelling and grammar. You can suppose that worked to a degree, but you can also chalk up many of your spelling errors to the fact that he simply made a lot of it up (you could do that then). Because of the movement at the time to fawn over Latin and Greek as perfect languages, he chose to spell things in ways that he incorrectly thought reflected Latin and Greek spelling—thus turning English into a kind of lexical frankenstein. For example he preferred the spelling 'ache' to 'ake' because he incorrectly thought it came from the Greek 'achos'; he also was inconsistent, keeping the 'p' in 'receipt' but leaving it out of 'deceit'. Of course, his writing these things down had the annoying consequence of making them pseudo-permanent and this in turn led to the conspiracy of 'Standard English'. Arguably, Standard English makes certain things more efficient—you wouldn't want to have to decipher a different version of the 'ACHECEIPT' sign every time you wanted to find your way out of burning building. However, it has also allowed us to discriminate against people who simply don’t know 'the language'—as if someone owned that definition.

Language is also influenced by our capacity to learn it. With some colleagues, I recently did some research on the influence between languages in early bilinguals. Using something similar to social network analyses, we looked at the semantic structure of over 500 children's early vocabularies. What we found was that bilingual children tend to overlearn words that are semantically synonomous in both languages (i.e., translational equivalents), like 'dog' and the German 'Hund', or 'ball' and the Spanish 'pelota'. This is surprisingly opposite of what one would predict from theory based on monolinguals, where children are commonly observed to avoid learning two words for the same concept.

So what might be the implications of this? Well, for one it may mean that the better you know your own language, the easier it is to learn another. It may however also mean that bilinguals tend to learn—at least when they're young—slightly different versions of languages than comparable monolinguals. If you scale this up, it could change the world. Here's how.

A recent study by Lupyan and Dale found that, among a group of more than 2000 languages, languages spoken by larger populations tended to be morphologically simpler. That is, instead of having five different obligatory ways to use the past tense depending on how far back in time something happened—like Yagua, a language of Peru with about 5000 speakers—languages with more speakers, like English, tend to just say 'was'. Lupyan and Dale argue this is because languages with more speakers tend to be under the influence of a great deal more second language learning, which means the languages have to be more learnable. UNESCO recently made the claim that more than half of the world's population is bilingual, and this number appears to be growing. So a toast to the inevitable rise in simplicity—and, in the meantime, you can do your part by learning another language.

Lupyan, G., and Dale, R. Language structure is partly determined by social structure. PloS one 5.1 (2010): e8559.

Bilson, S., Yoshida, H, & Hills, T. Language acquisition of bilingual children: a network analyis. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2014.

You can follow Thomas on twitter here.