Suicide

Suicide and Compassion

It seems wise to avoid judging the self-destructive actions of others.

Posted November 18, 2013

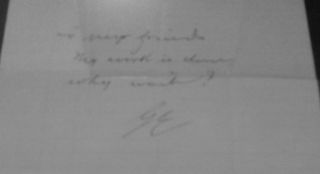

“To my friends, my work is done... Why wait?”

George Eastman House, Rochester, NY

This was the suicide note of inventor and philanthropist, George Eastman, best known for Kodak, the photography company he started. He was 77 when he died, on 14th March 1932, having suffered a painful and debilitating back condition for some years.

On that last day, the ageing bachelor signed final papers allocating his estate to various beneficiaries. As they were descending the staircase, about to leave Eastman’s magnificent house, his lawyers heard a loud bang. Eastman had shot himself in the heart.

This was a determined and clearly premeditated act of suicide. However, although Eastman asked that final question, ‘Why wait?’, he did not give anyone time to answer. There may be plenty of reasons to wait, even after we consider our work finished, and even if we are weak and in pain. Eastman, for example, might have come up with at least one more helpful invention. Who can say?

We are wise, though, to approach his and every suicide with understanding and compassion. It is not for us to judge either George Eastman or any other person who takes his or her own life. Who knows how each of us might behave in similar circumstances?

Over many years of practising psychiatry, I have known a number of people who took their own lives while suffering from severe and enduring forms of mental illness; mostly depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Fortunately, there were not that many, and I can remember something about each of them. Their illnesses were among the most severe and treatment-resistant that I came across. Each was predicted to be at high risk of eventual suicide, but the timing of the suicidal act could not be predicted. In any case, one patient under constant observation still managed to evade supervision for long enough to leave the hospital and find a high place to leap to her death.

Eastman's final note

None of these patients was particularly young. All had been unwell since their teens or early twenties. My own experience in each case was sadness, and regret that we did not have more effective treatments. As I recall these separate individuals now, I am aware how much they each suffered, and how tempted I might have been to follow their suicidal example if I had been in a similar predicament. Some might have been responding to delusions and hallucinations, hearing voices telling them to kill themselves, for example, but in the cases I recall it seems more likely that, like George Eastman maybe, they were making clear-minded choices to put an end to their loneliness and emotional pain.

Rather than ‘committing’ suicide, as if it were an anti-social or criminal act, I prefer to think that they ‘died by suicide’ as a consequence of their illnesses and the unremitting accompanying psychological distress. A better term than ‘suicide’ might therefore be ‘auto-euthanasia’; release by their own hands, in other words, from an incurable disease.

The staircase at George Eastman House

One of my patients who died by suicide, an elderly woman, was married. She had no children. The others were solitary people. In most cases the severity of their illnesses had prevented them from forming and maintaining lasting relationships. They had no mourners, apart from those of us working with them who had grown to look upon them with a degree of affection. This really happened because, when the illness was not overpowering them, they were all straightforward, likeable people.

Suicide often leaves surviving family members and carers with powerful negative feelings. As well as sadness at the loss, because it is usually so hard for survivors to comprehend, a suicide in the family often results in a strong feeling of shame. So, it would be good to rid suicide of its stigma, to free survivors from the sense of humiliation and public disgrace. Let me repeat, then, that ‘carrying out auto-euthanasia’ offers a better description than ‘committing suicide’.

Also, remembering George Eastman, as well as my patients, let me again recommend understanding and compassion in every case.

Copyright Larry Culliford

Larry’s books include ‘The Psychology of Spirituality’, ‘Love, Healing & Happiness’ and (as Patrick Whiteside) ‘The Little Book of Happiness’ and ‘Happiness: The 30 Day Guide’ (personally endorsed by HH The Dalai Lama).

See Larry interview J C Mac about 'spiritual emergence' on You Tube (5 min).

Listen to Larry's Keynote Address to the British Psychological Society's Transpersonal Section via You Tube (1 hr 12 min)