Maybe you don’t think of statistics as sexy. But Christian Rudder might very well change your mind about that. Rudder was a math major at Harvard. Instead of applying his quantitative skills to financial markets or engineering, though, he put them to use developing a computer dating service (called OKCupid). Now, you might not think of a dating service as a serious scientific endeavor, but Rudder has managed to mine the information from millions and millions of lonely hearts to reveal some surprising patterns of human choice. And given that sexual reproduction is at the center of biological evolution, those patterns really matter to anyone who wants to understand human nature.

Some of what Rudder has uncovered is simply amusing. As I discussed a while back, Rudder’s data-mining revealed that the single question that best predicts whether a woman will sleep with a fellow on the first date is not where she stands on the religious or political spectrum, but instead whether she says “yes” to the question: “Do you like the taste of beer.” (see What's the one best question to predict casual sex?)

Big Data as a Window into our Secret Sentiments

In a new book, called Dataclysm, Rudder advances a very interesting argument: If you want hard scientific facts about what people really want, and what they really feel, you couldn’t do much better than examining which keys people punch on dating websites, and how fast they punch them. Those millions of keypunches can inform us how people behave when they think no one is looking. Online data services are just one form of what is now called “Big Data” – a term for the same sort of massive information crunching that allows amazon.com to make a decent guess about which new books or kitchen products you might want to purchase next, or that helps iTunes predict which new bands you might want to add to the collection on your iPod, iPhone, or iPad.

In Rudder’s book, he notes a number of interesting findings he’s been able to cull from which photos men and women click on when they are looking for dates. For example, he can answer the question: Who is more racially selective in their choices: Asians, blacks, Latinos, or whites? And within each group, are the women or the men more racially biased? When psychologists study stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination in the laboratory, they face several obstacles. For one thing, the college students who participate in most lab experiments know that discrimination is un-American and generally frowned upon. For another, college students may be unrepresentative of the broader population in the world, so there may be insufficient numbers of certain racial groups to draw conclusions. But Rudder was able to get data from 3 dating websites that included 20 million men and women from the major racial and ethnic groups that make up the United States population. So, he could answer that question in a way that psychologists can’t. You can find the details in his book, but in general, men are a lot less selective (or biased) in their choices.

Are 60-year-old men really interested in 23-year-old women?

I was particularly fascinated by the findings Rudder presents in one of his chapters – which presented data suggesting not only that men and women differ in the age of potential partners they most prefer, but that the sex difference is much greater than you might have guessed. The question of age preferences in desired mates is not a trivial issue: It raises important scientific questions, about the evolution of human mating patterns, and it has practical implications, since the sex discrepancy leaves a lot of older women, and very young guys, facing suboptimal prospects if they are looking for a life partner. My colleagues and I have delved into this question in several scientific papers. In one paper in the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Rich Keefe and I presented an extensive series of studies from marriages in the Philippines and the United States, marriage advertisements in India, singles ads in the Netherlands and Germany, as well as analyses of U.N. data on marriage ages in remote regions around the globe. In other papers, we have teamed up with Bram Buunk of the University of Groningen and other colleagues, to report survey results from samples ranging from teenagers in New Mexico to senior citizens in the Netherlands. Other researchers have responded to our arguments with data from South America and Africa. I describe a lot of this research in Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life. Despite all that prior work, though, Rudder’s “Big Data” is able to throw a new spin on the topic, strongly corroborating some of the central assumptions of the existing work, and even contributing some new insights to what we already knew.

Several decades ago, researchers interested in mate choice realized that there was a goldmine of easily accessible data on mate preferences in so-called “single’s advertisements.” Newspaper advertisments were becoming an increasingly popular way of connecting with members of the opposite sex (or with your own sex, if your preferences leaned that way). In a singles ad, people had to pay by the word to describe themselves and what they wanted in a partner, a practice that rewarded concise ads, as in: “Single white male age 35 seeking athletic outdoorsy woman age 25 to 35. Non-smokers preferred.” Social scientists during the 1970s and 1980s found those ads useful in a couple of ways: First, unlike questionnaires in a laboratory, they gave a closer approximation of what people really wanted in a mate. Second, the people who took out those advertisements were not just 20 year-old college students, but ranged in ages, occupations, and so on. An additional nicety is that they were anonymous and available by the thousands, without the time and inconvenience involved in bringing subjects into the laboratory, having them fill out informed consent forms, and wondering whether the very act of being observed might be changing what they said.

The first researchers who analyzed these singles’ ads observed something that, at first blush, seemed obvious and uninteresting: The average young man advertised for a woman who was, on average, one or two years younger than himself, and the average young woman advertised for a guy who was a year or two older than herself. That average age difference was frequently attributed to something about the “norms of American society” which (as the story went) stipulated that a woman “should be” younger, shorter, and less educated, so that she could “look up to” her male partner.

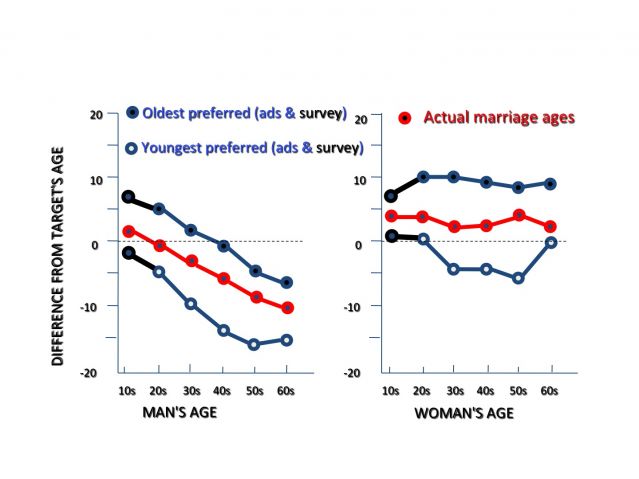

We took another look at data from singles’ ads in the U.S., and compared them to actual marriages around the world, and found that, when one looked more carefully, the standard explanation didn’t quite work out. For one thing, young men are not especially attracted to younger women. In fact, teenage boys violate the supposed norm by being attracted to older, college-age, women (despite a full awareness that their interests were not reciprocated). For another, gray-haired men were not interested in women one or two years younger, but instead interested in women ten or twelve years younger. Why the complications? We speculated older men’s interest in younger women was linked to the fact that women go through menopause and are no longer fertile, and conversely for fourteen-year-olds lack of interest in eleven and twelve-year-olds (who are not yet fertile). Figure 1 shows some of the results of our research.

Results from Behavioral & Brain Sciences and Developmental Psychology

But if men are, in theory, seeking a fertile partner, why don’t sixty-year-old men advertise for twenty-two-year old women?

There are several possible answers to that question. For one thing, mate choice is reciprocal, and maybe the average aging fellow realizes that those twenty-two year old women are not going to be interested in him, unless he has a lot of wealth to make up for the fact that he is not only less physically fit than the younger guys who are also courting her, but also less likely to live long enough to help her take care of her children. Both sexes might also guess that it is harder to establish a comfortable relationship when one partner has old-fashioned values and a collection of Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett records, whereas the other is a modern progressive who doesn’t know what a “record player” is, and only listens to digital recordings of Jay Z, Rihanna, and Kanye West. Another possibility is that older men’s taste in women matures as they do, so that a 60-year-old man actually prefers the appearance of a nicely dressed 45 or 50-year-old woman over that of some young girl with a nose-ring, a tattoo, and her hair dyed pink.

Enter those millions of anonymous mouse-clicks on online dating services. Unlike old fashioned newspaper ads, online dating involves photos, more info, and tracks the actual dynamics of people checking one another out.

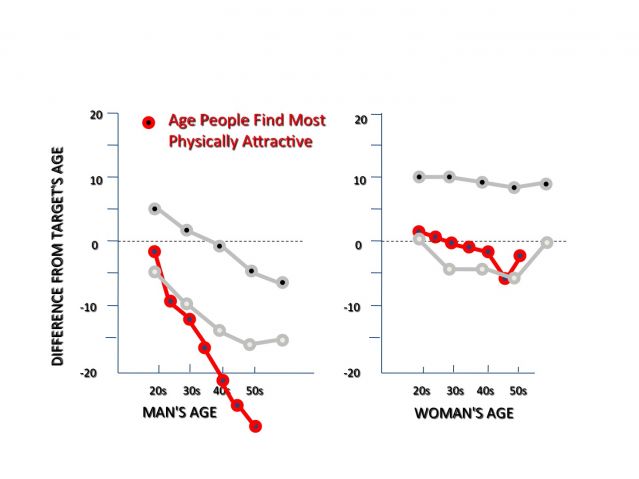

Here is a graph from Rudder’s book showing the ages of the men whose photos women click on. What you see if you look at the red line on the right is that women’s tastes in men map reasonably well onto the ages of the men they are likely to advertise for, and to marry (the gray bars are from our earlier data).

Rudder's Big Data reveals extreme preferences in men

But now take a look at the men’s clicks (the red line on the left). Regardless of the man’s age, he is most likely to click on the profiles of women between the ages of 20 and 24. So, a 20-year-old guy and his 65-year-old grandfather are in fact attracted to women of the same age!

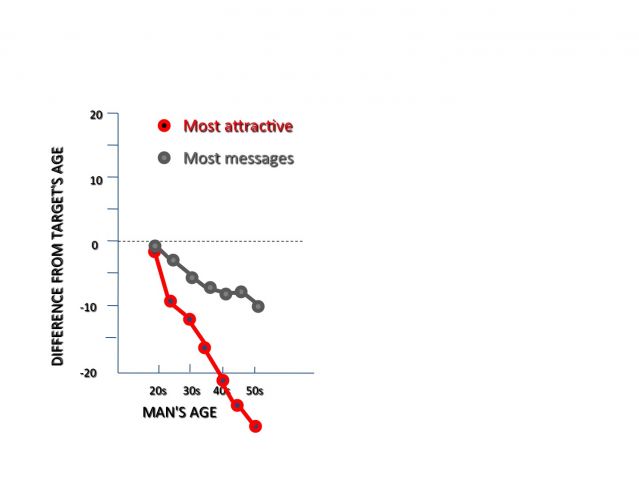

However, Rudder points out that there is another interesting wrinkle in the Big Data set. Although older men spend a lot of time looking at those very young women, they are much more likely to attempt to contact women whose age is somewhere between their own ripe-old age, and the nubile young women to whom their eyes seem to be drawn.

Men's messages do not map onto their attractiveness ratings

Rudder comments that the old men are making a “pathetic compromise” between “what men imagine they’re supposed to desire, versus what they actually do (desire).” But I think that he is being overly derisive in his assessment, and not quite right about what is being compromised. In fact, some of my colleagues and I collected some “Small Data” in the Netherlands in which we asked respondents to tell us the ideal age of a romantic partner. We found that the answer differed greatly depending on whether they were talking about a partner for a casual sexual affair or a long-term marital relationship. For sexual partners, men of all ages preferred much younger women. But for marital partners, they preferred women somewhere in between their own age and the age of maximum fertility. Women made a similar, but less extreme, distinction: they preferred men their own age for marital partners, but for sexual partners, they were open to a wider range of ages (from around their age to somewhat younger men).

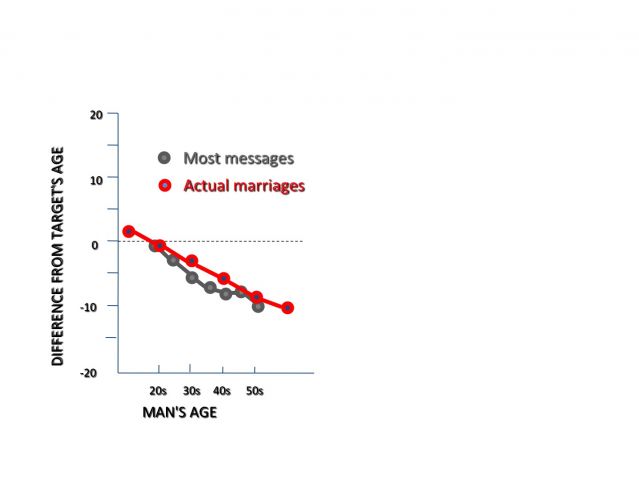

So, older men are perfectly willing to admit an interest in much younger sexual partners, just as their teenage grandsons are willing to admit an interest in college-age women. Neither group expects to be getting much sexual interest back from those 22-year-old women, incidentally. Thus, when men say their ideal marital partner is a bit closer to their own age, it is a compromise, of a sort. But biologists who study the life histories of different animals note that all living organisms are always making compromises, less derisively known as "trade-offs." You can’t maximize everything, and if you are investing in finding a new mate you must use time and energy you could use to take care of your existing offspring or to rebuild your own body. Older men may feel sexual attraction toward very young women, but most of them do not want to pay the price of sacrificing the chance for a mutually satisfying long-term relationship (with a partner who could help them survive and take care of their grandchildren, even if she’d be less fun at a wet t-shirt party). Indeed, as you can see in Figure 4, Rudder's results for who men actually talk to maps quite nicely onto our earlier data for who they actually marry (from Figure 1).

Figure 4: Men's online messages compared to actual marriages

A half-informed book review

Should you buy Rudder’s Dataclysm? Since I am only halfway through the book, I am not really qualified to write an official “book review.” Nevertheless, I can say that the book is engaging, thought-provoking, and interesting. Although Rudder is not himself a social scientist, he is a keen observer with a great sense of how to use Big Data to reveal intrinsically interesting aspects of human nature. And he’s an entertaining writer, who actually manages to make statistics sexy.

Douglas Kenrick is author of The rational animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think. and of Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life:A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature.

Related blogs

What's the one best question to predict casual sex?

The mind as a coloring book: Universal mechanisms reveal surprising cultural diversity.

The mind as a coloring book: Why cultural diversity does mean a blank slate mind.

Never tell a woman you love her (unless...)

Young girls and seductive older men: An education, about male and female psychology.

References

Buunk, B.P., Dijkstra, P., Fetchenhauer, D., & Kenrick, D.T. (2002). Age and gender differences in mate selection criteria for various involvement levels. Personal Relationships, 9, 271-278.

Buunk, B.P., Dijstra, P., Kenrick, D.T., & Warntjes, A. (2001). Age Differences in Preferences for Mates are related to gender, own age, and involvement level. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22, 241-250.

Kenrick, D.T. (2011). Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature. New York: Basic.

Kenrick, D.T., Gabrielidis, C., Keefe, R.C., & Cornelius, J. (1996). Adolescents' age preferences for dating partners: Support for an evolutionary model of life-history strategies. Child Development, 67, 1499-1511.

Kenrick, D.T., & Keefe, R.C. (1992). Age preferences in mates reflect sex differences in mating strategies. (target article) Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 15, 75- 91.

Rudder, C. (2014). Dataclysm: Who We Are (when we think no one's looking). New York: Crown.