Leadership

Management by Discovery

Sometimes we have to give up our original goals.

Posted October 12, 2014

If you don’t understand your destination, there’s no telling where you might wind up. And since time is short and resources are limited, there’s not much margin for wasted effort. Business leaders may have ambitious plans, but once the plans get the go-ahead, the program and project managers have to deliver within budget and schedule.

The standard game plan is to rely on some version of Management by Objectives: Define the desired end state, then work backwards to identify the necessary tasks, work out the schedule for each task, assign responsibilities to the team members, and get started.

If only the world was so cooperative. Unexpected events can throw even the most carefully defined plan into confusion. Skilled managers have to be able to adapt and perform tradeoffs between different goals and constraints.

And then there is the challenge of wicked problems: goals and objectives that cannot be carefully defined in advance. Problems for which there is no “right” answer. Fixing the healthcare system in the U.S. is an example of a wicked problem because different stakeholders have competing needs and would argue about the merits and drawbacks of any proposed solution. Wicked problems can arise because not enough is known at the outset to specify all features of the goal, or because there is no optimal solution, or because of different stakeholder communities, or because a rapidly changing context is likely to render the original goals irrelevant.

Lower-level managers are usually given straightforward projects with clearly defined goals, but as they move to positions of greater authority, they are more likely to have to wrestle with wicked problems. Unfortunately, their previous success in tenaciously pursuing the initial goals may now get in their way because wicked problems demand that we revise, not our plans and tasks, but the goals themselves. Research has shown that most mid-level managers cling to their original goals even after it is clear to them that those goals are obsolete.

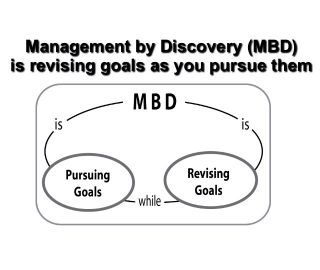

Here is where Management by Discovery comes into play. If the project or program is sufficiently important, the managers will have to start work even with goals that are somewhat vague. They are more likely to achieve an acceptable outcome if they can modify the goals along the way, making discoveries rather than rigidly clinging to the initial objectives

The concept of Management by Discovery is that adaptive leaders and managers try to learn more about the goals even as they are pursuing them. Wicked problems won’t clarify themselves. The only way to make progress is to gain insights about the goals by struggling, learning and adapting. (Clayton Christensen refers to this as discovery-based planning, in "The Innovator's Dilemma.") If the premise of Management by Discovery makes conventional managers uncomfortable, they should consider the software industry. After many years of cost overruns and rejected products, software firms pioneered techniques for rapid review and revision cycles to accommodate the discovery process. But other industries can’t seem to break free from the traditional planning mindset. They rely on practices such as tying payments to the initial schedule and conducting progress reviews to measure cost and expenditures as specified in the original plan. These practices fit well-ordered tasks, but they become barriers to the insights and discoveries needed when facing wicked problems. I have described Management by Discovery in more detail in my book Streetlights and Shadows: Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision Making. And in the Triple Path model of insights, the outcomes of an insight is to change what we understand, what actions we can take, what we see, what we feel and what we desire. Management by Discovery hits on this last component, gaining insights about what we desire.