Child Development

5 Ways to Read Aloud to Babies and Reap Later School Success

Pediatricians want you to read aloud—but how?

Posted July 17, 2014

The American Academy of Pediatrics just announced a new policy: Read aloud to infants from birth! Now every time the baby visits the office 62,000 pediatricians across the country will prescribe reading aloud. [1] But will reading aloud to your preschooler carry over to academic success in school? The answer is “yes,” especially if you use five research-based reading aloud strategies.

The new policy is being advanced by brain science which shows that the baby-reading brain is capable of laying down circuitry in the first three years of life. [2] For example, support circuitry for reading—developing word knowledge, sound and language development, even motivation to read—gear up beginning in infancy. [3] White matter for word reading can be in place as early as nine months of age. [4]

But research shows that most adults don’t know how to read aloud to preschoolers. [5] Here are five research-based strategies:

5 Research-Based Strategies for Reading Aloud to Preschoolers

1. Talk to Your Baby When You Read Aloud

When you read aloud to babies and toddlers, be conversational. Talk to them to explain things or focus their attention. Repeated readings of favorite books allow you to create a conversation around the reading with lots of opportunities to pause, reflect, point out, and comment.

Speak normally when reading aloud and avoid nonsense “baby talk.” Babies respond well to a high-pitched, highly intonated, singsong style of speech called “motherese” which is slower and slightly louder than ordinary speech offering more contrast between syllables and words. Motherese comes naturally to most parents; fathers should use it too. [6]

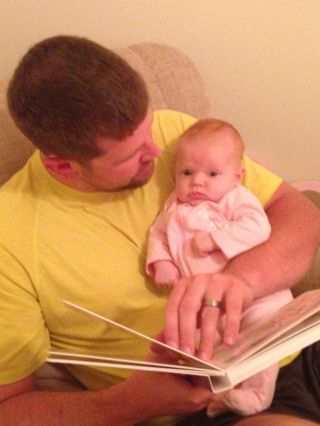

Dad reads to Baby Ruby

“More talk” to babies is supported by research. In a classic study children who interacted with a greater volume of conversation in the first three years of life had higher IQ’s and became better readers, writers, and spellers in third grade. [7]

2. Be Positive—Make it Fun

Your baby likes your attention. This is where motivation to read begins. Books and reading aloud become associated with good feelings and help create a bond of comfort and love. Choose books that are simple, clear, and happy. Make it fun by using animal noises, exaggerated expression and actions when appropriate. Stop when your baby seems uninterested and try again later.

3. Give Your Toddler a High Dose of Print Knowledge

Whenever you read aloud and make references to letters and sounds or show left-to-right directionality of print in English, and when you track words in print with your finger or ask questions using print related terminology such as “what is a word” or “how do you spell … so and so,” you are helping your child develop “print knowledge.”

A recent ground breaking study, Shayne Piasta and fellow developmental psychologists at The Ohio State University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Toledo tracked the print knowledge development of 550 four year olds in 85 classrooms. They found that children who received moderate and high doses of print knowledge during reading aloud were better readers and spellers two years later in school. The study showed that making references to print when reading aloud actually caused kids to do better later in school.

So in order to help your child read, comprehend, and speak better in school, read aloud with high doses of “print knowledge” during the preschool years. Interestingly, the study revealed that parents, teachers, and day-care providers did not routinely make print references when reading aloud so it’s a procedure that needs to be developed consciously. [8]

4. Say It and Point to It

Piasta and her fellow researchers highlight two ways to increase your child’s attention to print during storybook reading: 1) talk about print knowledge from time to time or 2) point it out. There were advantages to calling attention to letters, letter features, sounds, or other aspects of print both verbally and by pointing. [9]

5. Read Aloud Often

The new American Academy of Pediatrics policy recommends that parents engage in “reading together as a daily fun family activity” beginning in babyhood. In the Piasta study with preschool teachers a “high dose” of explicit print references consisted of four reading sessions per week for 30 weeks. [10] A bedtime reading routine works well. In general, it’s recommended that parents read a few minutes at least twice a day for at least five or ten minutes. That’s about the amount of time it takes to share an easy book. [11]

When it comes to reading aloud to babies and toddlers follow these five research-based strategies and remember, “more is more!”

For a look at The Top 10 Reasons to Teach Your Baby or Toddler to Read go to http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/raising-readers-writers-and-spellers/201107/the-top-10-reasons-teach-your-baby-or-toddler-read

[1.] Rich, M. (June 24, 2014). Pediatrics group to recommend reading aloud to children from birth The New York Times, p. A14.

[2] Eliot, L. (1999) What’s Going on in There? How the Brain and Mind Develop in the First Five Years of Life. New York: Bantam Books.

[3] Gentry, R. (2010) Raising Confident Readers: How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write—from Baby to Age 7. New York: Lifelong Books.

[4] Patricia Kuhl, “Cracking the Speech Code: Language and the Infant Brain” Pinkel Lecture, Institute for Research in Cognitive Science, University of Pennsylvania. April 16, 2010. For the full lecture go to http://www.ircs.upenn.edu/pinkel/lectures/kuhl/index.shtml.

[5] Piasta, S. B., Justice, L.M., McGinty, A.S., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2012) Increasing young children’s contact with print during shared reading: Longitudinal effects on literacy achievement. Child Development, 83, 3, 810–820.

[6] Gentry, R. (2010) Raising Confident Readers: How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write—from Baby to Age 7. New York: Lifelong Books.

[7] Hart, Betty, and Todd Risley. (1996) Meaningful Differences in everyday Experiences of Young American Children, Baltimore: Brookes.

[8] Piasta, S. B., Justice, L.M., McGinty, A.S., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2012) Increasing young children’s contact with print during shared reading: Longitudinal effects on literacy achievement. Child Development, 83, 3, 810–820.

[9] Piasta, S. B., Justice, L.M., McGinty, A.S., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2012) Increasing young children’s contact with print during shared reading: Longitudinal effects on literacy achievement. Child Development, 83, 3, 810–820.

[10] Piasta, S. B., Justice, L.M., McGinty, A.S., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2012) Increasing young children’s contact with print during shared reading: Longitudinal effects on literacy achievement. Child Development, 83, 3, 810–820.

[11] Gentry, R. (2010) Raising Confident Readers: How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write—from Baby to Age 7. New York: Lifelong Books.

(Dr. Gentry is the author of Raising Confident Readers, How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write--from Baby to Age 7. Available on Amazon.com. Follow Dr. Gentry on Facebook and on Twitter.)