If you are reading this, then lucky you; you’re alive. And not only that, but you live in the most you-centered age in history: the age of iTunes, iCloud, iPhones, iPads, and yes—even iCarly. Your customized world seems almost too good to be true, perfectly tailored to your own unique interests, passions and beliefs.

Exciting times, right?

Not so fast. A self-centered iCulture comes with some warning signs: Empathy among young people is on the decline. Americans are generally worse at taking other people’s perspectives. And as evidenced by our increasingly polarized political sphere, social narrow-mindedness is starting to have serious cultural consequences.

Social psychologists and the general public alike have long known that people prefer to be with others who are similar to them. Likewise, classic psychological research shows that people are "motivated reasoners," selfishly seeking to confirm what they already believe. In so doing, people go so far as to ignore or dismiss those inconvenient bits of information that might not jibe with their existing perspective (global warming being a prime example).

But these tendencies seem to have reached new levels in recent years. The Facebook “friends” we surround ourselves with are alarmingly similar to us in their pursuits, backgrounds, and worldviews. We disproportionately retweet politically like-minded people on Twitter. On TV, we tune into either MSNBC or Fox News, so that we hear what’s going on in the world in the way that we want. Even college—a traditional bastion of exposure to people of different backgrounds—threatens to become increasingly insulated, as more courses are offered online.

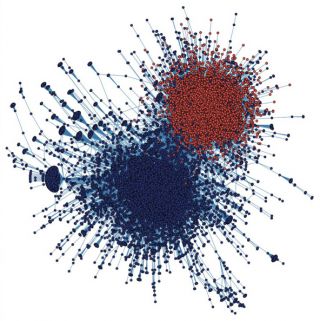

Political polarization on Twitter (Conover et al., 2011).

How did we get so myopically me-focused? There’s certainly no shortage of proposed explanations. Perhaps it’s "narcissistic" Generation Y’s fault, or "spoiled" Generation X’s. Maybe it’s the subtle cues we get from increasingly first-person-centric song lyrics. Or perhaps we should just blame the likes of Snooki.

Most likely, there isn’t any one particular explanation. Nevertheless, with businesses across the board increasingly personalizing their services, we are likely to continue glorifying who we already are. But if we buy the mounting evidence that creativity and ingenuity come from chance encounters and varying experiences (as discussed in Jonah Lehrer's bestselling Imagine and elsewhere), these are alarming trends. The potential for stumbling upon alternate viewpoints and broadening one’s own—on both sides of the political spectrum—seems unlikely in an ever-insulated social world.

This is not to say that people don’t theoretically value the ability to take others’ perspectives. President Obama might not have been elected if not for his hopeful pledge to foster compromise between political parties. And as evidenced by the plethora of how-to books on innovation, original, divergent thought appears to be a hot commodity.

But how can we think outside the box if we’re constantly sealing the lid shut? And how are we to negotiate with the other side when we increasingly don’t understand it?