Fear

Why I Voted for a Frack Free Denton

Despite a mega, pro-industry PR blitz the citizens-based movement won the vote.

Posted November 26, 2014

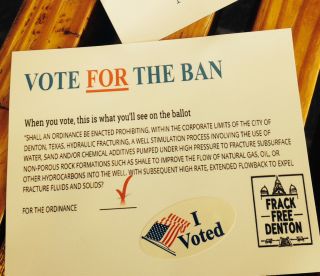

Postcard About the Fracking Ban in Denton, Texas

On November 4th, I joined Texas "Dentonites" to enact an ordinance prohibiting hydraulic fracturing within our city limits. I voted for a Frack Free Denton.

After the votes came in, Denton became the first city in The Lone Star state to put a legal limit on what it will permit the gas and oil industry to do within its borders. Despite a mega, pro-industry PR blitz that outspent the citizens-based movement ten to one and involved high-profile mouthpieces, huge printed billboards, mailings, phone calls, and door-to-door haranguing, the ban passed with 59 percent of the vote.

The Texas General Land Office and the Texas Oil & Gas Association already sought separate injunctions to keep the ban from being enforced. According to a lawsuit filed in county court, Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson called the ban a violation of the Texas constitution, with the state alone, not the city dwellers, controlling land use. The Texas Oil & Gas Association filed a separate suit claiming the opposite, that the ban robbed landowners of their property rights. Propaganda about why Denton constituents acted so recklessly to support the ban was full of castigation from officials who claimed that they/we “fell prey to scare tactics and mischaracterizations of the truth." In other words, fear mongering.

I've studied fear mongering -- the use of fear to influence the opinions and actions of others towards some specific end, often involving exaggeration of the feared object or subject, along with repetition to reinforce the intended effects of the tactic. Fear mongering is frequently used in public service and awareness campaigns.

In the months leading up to the election, it was actually the fracking industry itself and its supporters that used fear mongering extensively in an attempt to deter Denton citizens from voting for the ban. From diffusing anxieties about jeopardizing American security to irresponsibly affecting the financial health of our schools, fear was used strategically to engender a visceral response, all the while distracting attention from lax regulation, threats to human health, potential drop in property values, contamination of air, soil, and water, and the other concerns Denton citizens had been raising for years.

As a sociologist, the phenomenon was fascinating. As a citizen and resident, it was scary to see a politically supported industry focus its attention so squarely on putting the kibosh on informed enfranchisement.

Pro-fracking Propaganda

Are Citizens' Concerns About Fracking Well-Founded?

Within the last decade, the combination of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) with horizontal drilling has initiated large-scale drilling for natural gas across the United States. The fracking process begins with well construction, drilled into geologic formations that may contain large quantities of oil or gas, and then stimulates the release of these and other substances to the surface. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the process is as follows:

"Fluids, commonly made up of water and chemical additives, are pumped into a geologic formation at high pressure during hydraulic fracturing. When the pressure exceeds the rock strength, the fluids open or enlarge fractures that can extend several hundred feet away from the well. After the fractures are created, a propping agent is pumped into the fractures to keep them from closing when the pumping pressure is released. After fracturing is completed, the internal pressure of the geologic formation cause the injected fracturing fluids to rise to the surface where it may be stored in tanks or pits prior to disposal or recycling. Recovered fracturing fluids are referred to as flowback. Disposal options for flowback include discharge into surface water or underground injection."

The EPA's textbook definition of fracking is simple and straightforward. Implementation of the fracking process is not.

For example, a comprehensive and externally reviewed study of water use and waste generation from from Marcellus Shale fracking operations in West Virginia and Pennsylvania conducted by San Jose University and environmental consulting firm Down Stream Strategies found that a large proportion of the water injected to fracking wells comes from rivers and streams, and never returns to the surface. It is permanently removed from the water cycle, and the natural water sources used for fracking are not likely to sustain the industry going forward especially in times of drought. Additionally, the volume of waste generated in Pennsylvania went up 70 percent between 2010 and 2011 alone, of which 12 percent was shipped to waste sites in other states. High levels of contaminants identified in the flowback in these sites included bromide, barium, sodium, and iron. The researchers concluded that that even at the lowest levels of contamination, it would take one hundred times more water to dilute the polluted water enough to return to normal levels.

When the EPA evaluated the safety of fracking in 2004, it did so by reviewing information on 11 major U.S. coal basins to determine if the direct injection of fracturing fluids specifically threatened underground sources of drinking water (USDWs). The agency concluded that the risk posed to those underground sources of drinking water would be:

"Reduced significantly by groundwater production and injected fluid recovery, combined with the mitigating effects of dilution and dispersion, adsorption, and potentially biodegradation...Because EPA found that diesel fuel, which may pose some environmental concerns, was sometimes used in fluids for hydraulic fracturing...EPA reached an agreement with the major service companies to voluntarily eliminate diesel fuel from hydraulic fracturing fluids that are injected directly into USDWs for coalbed methane production."

Seeing little to no threat posed by this particular area of fracking (coal basin) on one specific resource (underground sources of drinking water) under precise conditions (groundwater protection, fluid recovery, mitigation measures, and the voluntary cessation of diesel fuel use), the EPA saw no reason to investigate the matter further. To protect the environment from potentially toxic fracking waste anyway, the EPA created a category of disposal wells specifically for the gas and oil industry. These Class II Wells were designed to pump "produced water" — a salty brine that may contain toxic metals and radioactive substances — back into the earth for eternal, safe storage. They are similar to Class I Wells earmarked for hazardous or non-hazardous industrial, municipal, or radioactive waste, but without the same regulation.

According to an investigative report by ProPublica (2012), the EPA's central data gathering system to obtain information on injection wells (launched in 2007) has been used by “less than half of the state and local regulatory agencies.” Few regulators supply information and only a small number of the nation’s deep, toxic-waste injection wells have complete data. Apparently, the EPA frequently accepts reports from state regulators that are "partly blank, contain conflicting figures or are missing key details.” In an EPA progress report (2012), the agency acknowledged that it had very limited information on the concentrations of chemicals being used in hydraulic fracturing.

With loose regulation and special dispensation regarding disposal, the fracking industry moved full speed ahead to new regions of the country. However, information surfaced about problems with the industry's waste disposal techniques, too many drilling accidents, a lack of full and consistent disclosures, excessive and wasteful water use, noise pollution, damage to urban and rural infrastructures, contamination of air, water and soil, and other issues.

In response to mounting public outrage in 2009, the EPA announced in March 2010 its intentions to conduct a study to investigate the potential impacts of hydraulic fracturing on drinking water resources. That is, specifically, what is the impact of large-scale water acquisition, well injection, surface spills of fracking fluids or flowback fluids on or near well pads, and inadequate wastewater treatment and disposal on drinking water sources? The study is ongoing.

Fracking processes clearly impact more than drinking water, but the EPA study is not designed to look at the potential effects of fracking on air, soil, ecosystems, wildlife, or health related factors. Nor will it consider regulation, reporting, disaster preparedness or remediation, or any of the other issues scientists and advocates continue to raise. Because the EPA does not have access to a complete listing of fracking wells, the study relies on self reported data from the nine major companies that comprise the fracking industry.

In 1988, the federal government changed its legal definition of hazardous waste to exclude elements resulting from oil and gas drilling, regardless of content or toxicity. This was a boon to the industry. But there is a strong desire for all sectors of society to take responsibility for safeguarding the environments in which people live and work regardless of energy demands and so-called threats to American security. Individuals and organizations are taking it upon themselves to investigate the impact of environmental changes on communities and public health; to learn about the regulations and industries that affect them; to look for big picture alternatives to toxic consumption; to advocate for policies and practices that will significantly improve public health and sustainability.

And when necessary, to ban industry altogether.

Dr. Gayle Sulik is the author of Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women's Health. More information is available on her website.

© 2014 Gayle Sulik, PhD ♦ Pink Ribbon Blues on Psychology Today