Adoption

Carcinoma: What's in a Name?

Experts suggest reclassifying some "cancers" to reduce overtreatment.

Posted July 31, 2013

As part of a National Cancer Institute working group, Dr. Laura J. Esserman MD, MBA of Mt Zion Carol Franc Buck Breast Cancer Center along with colleagues Ian Thompson MD of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and Brian Reid MD, PhD of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, wrote an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association explaining the working group’s recommendations to reclassify some of the conditions currently called “cancer.” They argue on behalf of the working group that the term “cancer” should only be used to describe conditions that have a “reasonable likelihood of lethal progression if left untreated.” That is, “cancer” has the capacity to spread (i.e., metastasize) to vital organs eventually causing death. A lesion (i.e., abnormal tissue) that does not spread and lead to death, or one that does not cause harm during a person’s lifetime, is by definition “not cancer."

The working group’s consensus that certain conditions currently called “cancer” should be reclassified comes after years of considerable discussion in the scientific and medical communities. The term “cancer” or “carcinoma” carries a negative and fearful connotation that does not accurately describe indolent conditions. As a result, the classification itself contributes to overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Overdiagnosis is the detection of cancers that, if left unattended, would not become clinically apparent or cause death, also called “indolent” tumors. Overdiagnosis occurs more frequently with cancer screening and is common in breast, lung, prostate, and thyroid cancer. Overdiagnosis frequently leads to the treatment of indolent conditions that would otherwise cause no harm (i.e., overtreatment). If an abnormality does not cause symptoms and is not likely to progress to cancer, the inherent risks associated with surgery, radiation, and/or hormone therapy such as side effects, anxiety and ongoing surveillance, increased medical costs, and a potential decline in overall health, may not be warranted, especially if the interventions fail to reduce the overall number of deaths. Treating an indolent condition that does not have the capacity to spread is a very different scenario from treating a localized cancer that does.

Although increased screening has led to an emphasis on early detection as the way to reduce cancer deaths, the detection and treatment of the earliest cancers of all – the indolent/precancerous lesions — have not, for breast and prostate cancers in particular, translated into a reduction in the number of invasive cancers (i.e., the types that have the capacity to spread and cause death). Instead, screening appears to detect more lesions that are potentially “clinically insignificant.” Increased screening of the general population increases the number of cases of indolent tumors found, thereby inflating overall incidence rates with little to no effect on mortality for the smaller population of more aggressive tumors. The steady mortality rates for those with aggressive cancers remains hidden beneath distorted survival statistics since the numbers include the indolent conditions.

Background: Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

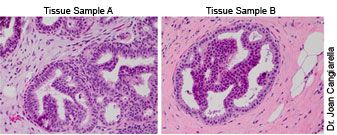

Sample A, low-grade DCIS; Sample B, atypical ductal hyperplasia

The indolent lesion at issue in breast cancer is ductal carcinoma in situ, DCIS, which is a proliferation of abnormal cells within the milk ducts of the breast. The widespread adoption of screening mammography in the US resulted in a substantial increase in DCIS diagnoses. In 1983, there were nearly 5,000 cases; in 1997, more than 36,000 cases; in 2010, 54,000 cases; today, about one in five new breast cancer cases are DCIS. A significant number of cases are borderline and subject to varying interpretation, such as the confusion between core biopsies that, upon further investigation, may be classified as either a collection of non-malignant abnormal cells or as low-grade DCIS. The cells in DCIS appear cancerous but because the cells have not invaded nearby tissue, DCIS is still not considered to be an invasive breast cancer. That is, as long as it remains DCIS, it cannot spread and is not life threatening.

DCIS is however a risk factor for the development of an invasive breast cancer. The problem is that it has not been possible to predict with any certainty which cases of DCIS would lead to the development of an invasive cancer and which would not. For this reason, DCIS is now almost always treated like a localized breast cancer. But the goal of treatment is to reduce the risk of recurrence or the development of an invasive breast cancer in the future. Because the biology of DCIS and its invasive tendency is poorly understood, and there is a sea of uncertainty surrounding which biological characteristics are most likely to indicate invasive potential, it is not clear whether all people treated for DCIS actually benefit from the interventions. The long-term, disease-free survival is 96-98 percent. High survival rates coupled with the noninvasive tendencies of the condition make treatment controversial.

What is the impact of treatment versus no treatment on patient outcomes? Should those diagnosed with this indolent condition be treated for breast cancer, or should they be considered at increased risk? Although these questions are part of the research agenda, they currently remain unanswered.

Yet there is enough data for the the National Cancer Institute’s working group to argue that, “An ideal screening intervention focuses on detection of disease that will ultimately cause harm, that is more likely to be cured if detected early, and for which curative treatments are more effective in early-stage disease.” Thus, they call for the removal of the “cancer” label for precancerous conditions such as ductal carcinoma in situ and others, along with the validation and adoption of molecular diagnostic tools to identify indolent or low-risk lesions and observational registries to monitor them over time. The goal is to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment, tailor treatment for “consequential cancers,” optimize screening programs, and provide patients and physicians with data to help them choose, with confidence, less invasive interventions. This level of agreement has been more than a decade in the making. Consistent with the data driven focus of evidence based medicine, it may indeed be the time for a change.

---

Dr. Gayle Sulik is the author of Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women's Health. More information is available on the author's website.

© 2013 Gayle Sulik, PhD ♦ Pink Ribbon Blues on Psychology Today