Parenting

Beth Kephart: Our House Is Still our Son's Home

Children move out, but the memories remain in our homes and hearts.

Posted January 30, 2014

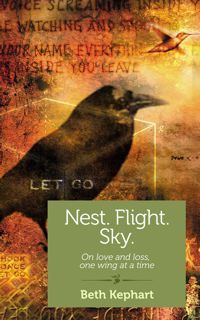

Contributed by Beth Kephart, author of the mini memoir, Nests. Flight. Sky., available on Shebooks.

This old house on this leafy street is quantifiable—a museum of animating things. A gesso wing. A palm-sized table. An envelope of watercolors. A few frames of funny men who wear their eyeballs on their sleeves. Bisqued faces, glazed vessels, pots in ancient earth tones. Like sun on water, like pink in clouds, like an egg in the nest of the tree, they hang, they sit, they wait, they tremble.

They are.

The books slouch triple thick on shelves, or tall in corner stacks, or quiet and aware in dark, underneath places. The photographs are the ones we took, or that others took—Salvadoran landscapes, a cratered lake, Venice in winter, Florence in autumn, Spoleto in the heat, Seville in the earliest parts of day, a gorgeous dark-haired son who grows up (there he is) frame upon frame.

There are glass apples on the windowsill, and a girl built of sticks with a bird on her head, and a sleek wooden giraffe that stands by the window looking out, and also two fine spinning wheels, a cluster of dried lotus pods, a closet full of faded baseball caps, a high school jacket on a hanger.

There is a hummingbird’s nest in a plastic bag and the tip of a tail of a baby lamb and a pair of glass fox eyes and the skull of a pine marten, and (in an adjacent place) a self-portrait built of crayon wax.

In the kitchen: jars of powdered chocolate and spices, a bag of saffron, recipes for the cookies he liked best until my father gave me my mother’s recipe book and I learned how to make her brownies.

In the window: papier-mache girls in flowered dresses hanging from transparent strings. Girls in flowered dresses beneath the shelter of balloons and kites.

In the bowl: a ripening pear.

Outside the wind chimes cling to a gnarly place in the trumpet vine, and the garden is an archipelago that blooms and suffers, and along the back of the house the bulbs of daffodils and gladioli do their inevitable things, and there is a soccer net that hasn’t been used for years, beneath the awning of trees.

This is the house.

This is what remains when the child who grew up frame by frame moves on—still dark-haired, now tall. “Love you,” his text comes in. Or, “Just saw Mike Tyson get out of a car.” Or, “Taking a walk by the river. Beautiful.” Or, “Figured out the start of my next story.” Or, “Work is good. Got a new account.” Flash nonfictions. News from the other side. Reports from the son who has a brilliant life of his own, in a city of his own, in a room of his own.

His own house.

His own things.

“You won’t believe what I just heard,” he texts.

“I think it’s going to snow,” he texts.

“Just saw Jason Stratham while eating dinner.”

Our children move on, their lives accelerate, their worlds are as big and as glorious as they make them, and that, of course, is what we want best and most, what gives us peace. Throughout it all, the old house stays where it was on the leafy street with the rather random garden and the leftover goal and the excess of baseball caps and the perfect crayon portrait.

The light changes. The quality of silence. There are shifts in the meaning of things. Background migrates toward foreground. Time takes on a gentle ping.

So that we sit for a longer time with the book of snapshots on our laps. He was so small, we were so young, we danced like that. So that we stand beside the giraffe, looking out on the street—two sentinels watching and remembering. So that we suddenly recall why we bought the glass eyes in the first place, and why we could not leave Asheville without that girl with the bird on her head, and why it was that we came to collect the nearly weightless girls that hang from their transparent strings, in their many flowered dresses.

In the absence of the children that we will always fiercely love, we have these things, these vessels, these funny faces, these eyes on sleeves, these ancient tones and buckling photographs, these places where our memories live. We have what we made, what we bought, what we read, what we saved, what we could offer, what we knew how to be.

We have what we became.

It’s all here, nearer, somehow, than it used to be.

Beth Kephart is the author of seventeen books. Her new book,

Beth Kephart is the author of seventeen books. Her new book,