Anger

Logical Fallacies and Games Without End: Countermoves

Illogical worst case scenarios, personal attacks, unending games: how to respond

Posted September 3, 2013

This post is Part 7 of my continuing series, How to Talk to Relatives about Family Dysfunction. In Part 1, I discussed why family members hate to discuss their chronic interpersonal difficulties with each other (metacommunication), and what usually happens when they try. I discussed the most common avoidance strategy — merely changing the subject (strategy #1)—as well as suggesting effective countermoves to keep a constructive conversation on track. In Part 2, I discussed the avoidance strategies of nitpicking (#2) and accusations of over-generalizing (#3). In Part 3, I discussed attempts to change the subject by getting into the blame game, and taking a shifting stance as to who exactly is to blame for a given family problem (#4). In Part 4, I discussed strategy #5, the use of fatalism to derail metacommunication, and strategy #6, the use of Non-sequiturs. In Part 5, I discussed #7, the fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc, and the use of Non-sequiturs. In Part 6, I discussed #8, the fallacy of begging the question.

To repeat: the goal of metacommunication is effective and empathic problem solving. As with all counter-strategies, maintaining empathy for the Other and persistence are key. I again repeat the strong caution: Please be advised that sticking to the counterstrategies that I describe may be extremely difficult, so the services of a therapist who knows about these patterns are often necessary. For families in which violence and/or shattering invalidation of people who speak up is common, a therapist who can coach you in effectively employing the techniques is essential. Also, the advice in my posts is designed for adults dealing with other adults. It is not meant for metacommunciation with children and teens.

Today’s post will describe two last logical fallacies, arguing from worst case scenarios (Strategy #9), and ad hominem or personal attacks (#10). I will describe the strategy for countering communications based on logical fallacies in general, as well as how to counter the game without end.

Strategy #9. An argument is often made that a particular course of action is ill-advised because of difficulties that might arise in a worst-case scenario. In other words, one asks the question, "If I did so and so, what would be the consequences if everything possible went wrong?"

Posing a worst-case scenario does not always mean that the poser is engaged in an illogical maneuver. Indeed, for certain questions, such as whether to build a nuclear reactor near an earthquake fault, looking at worst-case scenarios can be a matter of life and death. Residents of Fukushima, Japan, will know exactly what I am talking about.

Posing a worst-case scenario does not always mean that the poser is engaged in an illogical maneuver. Indeed, for certain questions, such as whether to build a nuclear reactor near an earthquake fault, looking at worst-case scenarios can be a matter of life and death. Residents of Fukushima, Japan, will know exactly what I am talking about.

The worst-case argument becomes logically suspect if it is being used as an excuse to avoid some action when either of two conditions is present. The first is when the worst case is so unlikely to occur as to be almost meaningless. The second is when the worst case is preventable.

The most common usage of the maneuver in psychotherapy cases occurs when patients attempt to suppress some aspect of themselves by frightening themselves with the thought of dreadful consequences should the characteristic of self ever be expressed. One of the most often seen examples of this involves the question of whether or not to express anger.

I once was the therapist for a group where every single member was in complete agreement that anger should be kept to oneself. They all painted a most shocking picture of the dire consequences that might ensue if their anger were ever to be unleashed. The anger would be destructive to the nth degree.

Everyone present said they had so much anger inside that if some of it got out, a dam would burst and a flood of violent fury would come pouring out. They might murder all of their loved ones and bomb government buildings. They might tear the objects of their rage limb from limb and end up on death row.

If thoughts like that did not scare them into keeping their anger quiet, nothing would.

The worst-case scenario that was proposed by the group members is illogical for several reasons. First, it is based on the non sequitur "If I let out some of my anger, I'll let it all out." How did they come to the conclusion that they would have more difficulty restraining themselves once some of the anger had emerged than before the process started? In fact, they were each masters at self-restraint.

While it is often true that people who have been stuffing their anger for a long time may suddenly explode when there is a "last straw," this usually occurs in the heat of the moment, not when one is planning how to bring up for discussion anger-provoking behavior. For this reason, the situation is not really analogous to the Dutch boy with his finger in the dike. One can always catch oneself.

Indeed, the extra guilt these people probably would feel for having exhibited angry feelings might make it even easier for them to restrain themselves in the future. This worst case, in which all of a limitless amount of anger would come out in a deluge is a highly unlikely worst case. Furthermore, this worse case is preventable.

Acting out the anger is hardly the only way to express it. One can talk to the anger-provoking person in a constructive attempt to get them to knock off the provocations.

The use of terrifying imagery to scare oneself out of a course of action is a very clear example of what I mean by mortification. In this case, an aspect of self, the emotion of anger, is suppressed by frightening oneself with worries about horrific consequences. Cognitive therapists may get upset with me for saying this, but irrational thoughts can serve the same function as defense mechanisms.

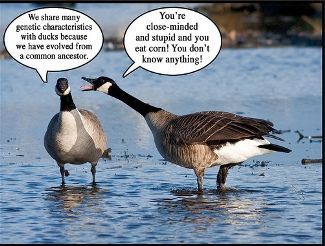

Strategy #10. Ad hominem translates from the Latin as "to the man." This fallacy is based on the non sequitur, "if a person is reprehensible in some respect, then everything that person has to say is incorrect." This fallacy is frequently encountered outside the metacommunicative realm in the area of politics. Just because Fidel Castro is a Communist autocrat and lies a lot, for example, one could not conclude that he is always lying whenever he made accusations against the United States government.

In metacommunication, family members will frequently discount an idea because of the alleged motivation of the person making it, without addressing the actual merits of the idea. The metacommunicator might be accused of being insincere or having some sort of ulterior motive for making an observation while the target completely ignores the merits of the observation itself.

Invalidation is a form of an ad hominem attack. The person bringing up a past event is accused of distorting it, or even making it up. This situation usually leads to a fight-or-flight response on the part of the metacommunicator, which stops the effort to solve interpersonal problems in its tracks.

And now at long last, what does the metacommunicator do when faced with a person who uses illogical arguments to avoid dealing with an uncomfortable interpersonal issue?

Columbo The basic response is what many therapists refer to as the

Columbo

The basic response is what many therapists refer to as the

He would never act as if he believed that the suspect were purposely misleading him, although he obviously knew that was often really the case. The suspect would then try to “help out” the hapless cop by clarifying the apparent discrepancy, much to his own detriment.

In metacommunication, the object of this strategy is of course not to make the other person incriminate himself or herself, but to get past a block in order to proceed with appropriate, metacommunicative problem solving.

In response to a logical fallacy, the metacommunicator tactfully expresses confusion about what the target is saying, or points out seeming contradictions or illogical statements. This is done in an almost apologetic fashion. Rather than accusing the other of purposely being misleading or confusing, metacommuncators try to indicate that they themselves are taking responsibility for any lack of interpersonal understanding.

In addition to decreasing the target’s need to become defensive, this counterstrategy often leads the target to feel obliged to clear up the metacommunicator's confusion. In order to do so, he or she must drop the logical fallacy. When this happens, it is important that the metacommunicator seem grateful for the new clarity, and not have a kind of “I just knew you were irrational” attitude.

Now maintaining this bemused, self-effacing sort of style is often particularly difficult to do, especially if there is an ad hominem component to the target’s irrational argument. When confronted with irrational arguments, it can often be the metacommunicator who becomes defensive, and who is the one who derails the effort at problem solving. In this case, giving the other person the benefit of the doubt and acknowledging one’s own contribution to the problematic past interactions come in very handy.

Now for the antidote to the game without end. To briefly review a former post, people in a family system will almost invariably "test" any new, requested rule change in an annoying or insincere manner. They do it this way in order to give the person who is requesting the rule an "out" - just in case he or she really is uncomfortable with the change. Through their actions, they also take the blame themselves for any failure at changing the family rules Family members are so generous that way.

In order for the countermove to work, it is important for individuals requesting the change to freely admit that they are not completely comfortable with the changes, but only because they were raised to follow the old set of rules. They now see the error of the former ways, but it will take some time before they get comfortable with the changes.

When another family member then does the requested behavior in a half-baked or obnoxious way, the person requesting the change should first praise the person for trying to do what was asked for. Then and only then should the requester quibble with the way that the task had been performed.

For example, to the husband from the previous post who finally helped with the dishes but put them away in all the wrong cupboards, the wife should respond: "Thanks for doing the dishes, honey, I really appreciate it. But if you are going to move things around, please tell me so I know where everything is."

Another example from the previous post: a wife had been encouraging her husband to be more honest about his true feelings and not so closed off. Consequently, he began to express himself, but in an abrasive fashion- and in front of her boss. The wife here should wait until she is no longer furious with the husband for doing that, and then say, in private of course, "I'm really glad that you're being more open about your feelings, but I really wish you wouldn't do that in front of my boss."

Point, game, match.

In an upcoming series of posts about keeping efforts to metacommunicate on track, I will discuss the countermoves to far more aggressive, frightening, and/or frustrating responses – those often associated with individuals exhibiting traits consistent with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.