Marriage

What If Barack Obama’s Mother Had Had A Different Life?

What if Barack Obama’s mother had come of age during the sexual revolution?

Posted April 15, 2014

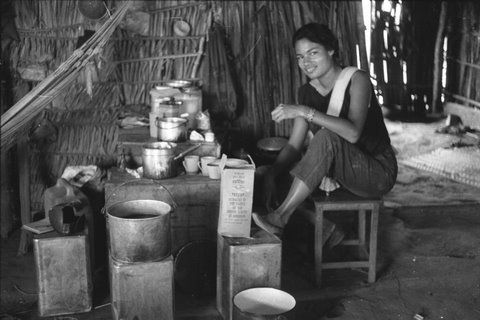

Ann Dunham with a villager in Lombok, Indonesia

Ever since I first read Dreams From My Father, I’ve been struck by similarities between my family and the one that Barack Obama grew up in. However, the parallels are between my wife and me and Obama’s parents—really just his mother, since his father was pretty much absent from his upbringing.

So my real curiosity was about Stanley Ann Dunham, Barack Obama’s mother; and when it was published I was eager to read Janny Scott’s appropriately titled biography, A Singular Woman. I wanted to learn more about Dunham, was interested in finding out how deep the similarities went, and wondered what lessons might be drawn from her life. (This essay has been lying dormant in my computer since the biography’s publication; and I recently decided to share it with my Psychology Today readers.)

In some ways, what I initially knew of the brief marriage of Ann Dunham (as she preferred to be called) to Barack Obama Sr., the birth of her son, and her career path, seemed as if someone had taken aspects of my marriage, jumbled them up, and rearranged them. I have written in my book, The Myth of Race about the effects on children of growing up in such families. In brief, the similarities are of American inter-racial families of anthropologist women who specialized in material culture, married social scientists, and gave their children atypical names and experiences of life in other cultures and with other languages.

Ann Dunham had a difficult life because she married early, was a single mom, and had to work very hard raising two children, earning a living to support them, studying, and doing research for her PhD dissertation. As I read about her adventurous, multifaceted and too-short life, I couldn’t help wondering whether, if she had made a few different choices, she might have had a personal and family life that turned out more like my wife’s and mine.

***

Ann Dunham, born two days after me, grew up in several white communities, during the Wonder Bread and Jell-O period of post-War anti-Communist witch-hunts and Jim Crow. As a bright and intellectual nonconformist, neither of whose parents had a college degree, she lacked access to a cosmopolitan milieu where she could develop her natural inclinations. Her glad-handing and less-than-successful father sought out job prospects in the new state of Hawaii, and he brought his hardworking and competent wife and high school graduate daughter with him. Ann enrolled at the University of Hawaii, where the new East-West Center provided her with the kind of intellectual stimulation she was looking for.

And not just intellectual stimulation. Ann met both of her husbands there—Barack Obama, Sr., a Kenyan, and Lolo Soetoro, an Indonesian. She arrived at the University in 1960 at the age of 17, and met and fell in love with Barack Obama, Sr., 23. She was impregnated by him before her 18th birthday, married him shortly thereafter, and through it all was unaware that he had another wife and child in Kenya. When she was 19, he graduated and went off to Harvard for graduate study in economics (where my wife, a year younger than he, was already a graduate student in anthropology); and the couple divorced when she was 21. During Obama Sr.’s absence and the failure of their marriage, she met Lolo Soetoro, and her second marriage took place shortly after her divorce.

1960 was before the pill, before the easy availability of and acceptance of contraception, before the sexual revolution, and before the civil rights and women’s movements. It was a time of back alley abortions and shotgun marriages, and it was not unusual for freshman women to marry. Given women’s limited job prospects and accompanying lack of career aspirations, college attendance was often seen as a luxury. Many were said to be “studying for their MRS degree.” That is, they viewed college as a place where they could meet and marry a fellow student, following which they might drop out of school to help support him and eventually start a family.

So Ann Dunham’s pregnancy and marriage during her freshman year weren’t all that unusual at the time. What was unusual was her husband. From all reports, Barack Obama, Sr. was a brilliant and charismatic man. It is not surprising that his attentions swept the teenager off her feet. Because he had already lived in Hawaii for a year, he doubtless understood American marriage customs, while Ann’s combination of youthful innocence and cross-cultural innocence prevented her from asking the right questions. She might never have imagined that a brilliant and charismatic man could be two-faced, or that polygyny could be an acceptable Luo practice.

Gender inequality is much greater in the Developing World than in the West. As a result, the issues facing Western women marrying someone from Asia, Africa, or Latin America are quite different from those facing men. For American men such marriages can be a win-win proposition. Their wives accept more homemaking responsibilities—cooking, childcare, and so forth—than American women might, and in exchange the American husbands treat them more equally and give them more personal freedom than they might have had at home.

For American women, such marriages tend to be a lose-lose proposition—especially when the wives go to live in their husbands’ countries of origin—as Ann Dunham did with Lolo Soetoro. The husbands—and the husbands’ families—may expect more deference and homemaking services than seem fair or acceptable to the wives; and the husbands may feel disillusioned or angered by their wives’ inappropriate behavior, desire for autonomy, and unwillingness to subordinate their needs to those of their husbands and the husbands’ families of origin.

For women from the Developing World, settling in the United States with their American husbands may seem like an attractive option, while for the men the best options may be returning home (with or without an American wife) or importing a wife—perhaps through a marriage arranged back home.

***

Dolores Newton at home in the Krikati village in the interior of the state of Maranhão, Brazil

Ann Dunham’s PhD dissertation, Peasant Blacksmithing in Indonesia: Surviving against All Odds, was in the small specialty area of anthropology known as material culture. Material culture provides a route to understanding a society through the study of its physical objects, the technologies associated with making them, and the ways they articulate with larger social contexts. It is a data-heavy area of investigation that is in some ways like an archaeology of living peoples. However, in addition to information about the artifacts themselves, there is a wealth of accompanying information to be gathered about: who made them and how; with what materials and processes (all in native language terms, with translations where possible); how the objects fit into the economy; who uses them, and how, and to what ends; aesthetic, religious, social, and utilitarian criteria for understanding and evaluating them; and so forth.

Because she had lived in Indonesia for so long and had so much data, it is understandable that Ann Dunham’s dissertation could have grown to 1,043 pages, and that it took her nearly 20 years to complete her PhD. It is understandable, but it is not acceptable. Janny Scott speaks glowingly, and no doubt deservedly so, about Alice Dewey--Ann’s dissertation mentor--as a professor, researcher, and human being. From my point of view, however, as a mentor, Dewey fell down on the job. A PhD dissertation can be an acceptable piece of research, or it can be an outstanding piece of research. But it cannot be and should not be a life’s work. Dewey did in the end make Dunham limit the scope of her dissertation, but I believe that she should have done so more radically and years earlier. (Because material culture is such a small specialty area, it is also possible that Dr. Dewey lacked the familiarity with the subject matter to know how to reshape the project into a more focused one.)

Perhaps as psychology professor I have a different view of the mentor’s role in dissertation research from that of anthropology professors. Psychologists aim at predicting and controlling behavior—a more activist perspective than anthropologists’ focus on observing and describing it. My wife, Dolores Newton, studied the material culture of a group of Timbira tribes, especially the Krikati, in the interior of Brazil; and her mentor, like Dewey, followed a hands-off policy. From early in our relationship, I struggled with Dolores to limit the scope of her dissertation. She finally reduced it from all of Timbira material culture (a project that remained unfinished at the end of her academic career) to Timbira cotton technology. As a result, her dissertation was “only” 357 pages long, and it took her “only” 13 years to complete her PhD.

If Ann Dunham had written a dissertation a third as long, with a more limited scope, and had finished it years earlier, her life would have been much easier. She could then have presented her additional data—including that omitted from her magnum opus—in a series of articles, monographs, and/or books over the course of her subsequent career as an anthropologist.

***

Here is one possible alternative life history for Ann Dunham—and one which might even have been likely, had she been born a few years later and come of age during the sexual revolution. Instead of marrying Barack Obama, Sr. she has an affair with him, during which the couple scrupulously practice birth control. The affair ends when he goes off to Harvard. She graduates on time and continues in the Anthropology PhD program at the University of Hawaii. She meets Lolo Soetoro during her graduate studies and has an affair with him, but the couple doesn’t marry because of her commitment to her studies. In addition, because she isn’t busy with childrearing responsibilities, she pays more attention to the news and learns of the political turmoil in Indonesia. As a result, she decides that Indonesia would be a fascinating place to study but not a place to spend her life. She marries another social scientist—perhaps an economist, sociologist, political scientist, psychologist, or anthropologist who is also interested in Indonesia, or perhaps an American-born son or grandson of Indonesian immigrants. By her mid 30s she (like my wife) completes her PhD with a dissertation of reasonable length, gives birth to her first child, and begins a career either in academia, or with an NGO focusing on peasant industry and women’s issues in Indonesia. She has a much easier and more rewarding life, though it is spent primarily in the United States rather than in Indonesia. Because she has adequate health insurance and health care, her cancer is nipped in the bud and she (like my wife and me) is alive today.

On the other hand, neither Barack Jr. nor Maya is born, and the country has a different 44th president.

Image Sources

Ann Dunham with a villager in Lombok, Indonesia (from Ann Dunham's Field Work Collection)

Dolores Newton at home in the Krikati village in the interior of the state of Maranhão, Brazil (from Dolores Newton's Field Work Collection)

Check out my most recent book, The Myth of Race, which debunks common misconceptions, as well as my other books at http://amazon.com/Jefferson-M.-Fish/e/B001H6NFUI

The Myth of Race is available on Amazon http://amzn.to/10ykaRU and Barnes & Noble http://bit.ly/XPbB6E

Friend/Like me on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/JeffersonFishAuthor

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@jeffersonfish

Visit my website: www.jeffersonfish.com