Beauty

It's An Acquired Taste: How Knowledge Drives Aesthetics

What we like is largely determined by cultural and personal knowledge.

Posted May 12, 2014

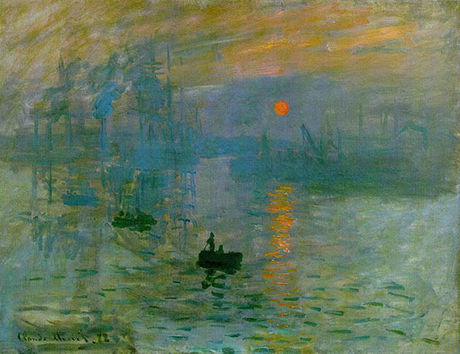

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise

Bebop, abstract art, sushi…people often say that it takes time to appreciate such things—that they are acquired tastes. Psychologically speaking, what does it mean for something to be uninteresting or even distasteful at first but then with time, gain in appreciation? In art, many styles when first encountered looked so perverse that their very status as "art" was questioned. Incredibly, this sentiment was true for Impressionist paintings as many 19th century beholders thought such works were ugly and crude. Even its namesake was based on a sarcastic review by Louis Leroy, a critic who in 1874 saw Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise and remarked: "Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape."

From our perspective, such sentiments seem so utterly off base as we now see beauty and grace in the same works. Yet these days it is not uncommon to hear at a contemporary gallery a visitor say to another, "Is that really art?" Clearly, what we know—from our cultural background and personal experiences—determines what we like. Thus, new works can appear odd and distasteful at first because we cannot easily incorporate them into our knowledge base. In music, bebop jazz, with its complex harmonic structures and syncopated rhythms, was a far cry from the traditional sounds of big band jazz and many found, and still find, the style too different or novel to be fully appreciated. With familiarity, new styles can acquire an attraction and may even become immensely pleasurable. With respect to musical trends—such as bebop, rock, and rap—one generation's "noise" is another's anthem to life.

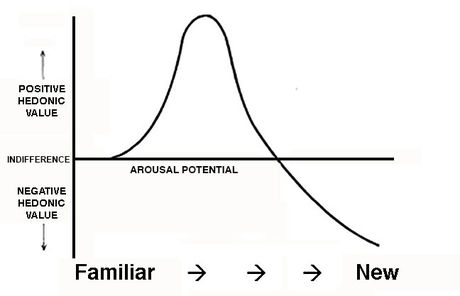

Daniel Berlyne, the prominent psychologist of aesthetics, argued that our art experience is driven by novelty, surprise, and incongruity, all of which increases arousal. He considered the Wundt curve, which was originally used to describe how increases in stimulus intensity, such as sweetness, is pleasurable up to a point but as intensity moves beyond that point our enjoyment drops and can even become negative.

The Wundt Curve

Berlyne argued that we find pleasure (i.e., positive hedonic value) when an artwork arouses our sense of novelty, surprise, or incongruity, but as the Wundt curve describes, when arousal moves past an optimal point it leads to a negative response. Importantly, the flip side of novelty is familiarity, and thus what appears new or surprising is a moving window, as the more you know, the more things become familiar and the greater chance a new work will lie in your "sweet spot" of optimal hedonic value.

In many ways, our own art experience recapitulates art history. Consider the mid-19th century beholder who had only seen the kind of realistic paintings displayed in parlors and salons at the time. Impressionist paintings may have been too surprising and too incongruous that they were judged negatively. With our 21st century eyes, we've experienced colorful abstractions not only in modern art museums but also in countless television and magazine ads. These days, Impressionist paintings may fall in our sweet spot of pleasurable experiences, as they appear as subtle abstractions of realistic scenes, but not so odd as to create discomfort. Further experience with modern art may garner a taste for such artists as Kandinsky, Pollock, and Martin. In 1906, Picasso painted a portrait of Gertrude Stein, the early collector of his works and those by Cezanne, Matisse, and Gauguin.

Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein

Earlier portraits by Picasso demonstrated his exquisite skill in painting naturalistic figures, but of course in 1906 he was keenly interested in experimenting with the visual form. One can see in this portrait the beginnings of his fascination with African masks. He seemed to be aware that knowledge is a vital feature of our art experience. A visitor, when confronted with the portrait said that Stein did not really look like that, Picasso replied, "She will."