Environment

The Surprising Reason We Don't Help and Why We Should Anyway

Research into what gives us a "warm glow" can help make us better people.

Posted April 28, 2014

Psychologists have known for a long time the emotional truth captured in Joseph Stalin’s chilling (reputed) observation, “One death is a tragedy. One million deaths is a statistic.” This apparent callousness to mass suffering is a version of "psychic numbing," in which the bigger the scope of the problem, the less impact you think you can have, so you care less, you donate less, and you help less, because against immense problems like mass murder or starvation, or climate change or other global environmental threats, helpless, ineffective, or powerless is precisely how you feel. This has been labeled the Drop in the Bucket Effect.

Studies have found that people will donate more to save two lives out of four potential victims, rather than save the same two lives if they are two of 1,700 possible victims. People donated more to provide clean water that would save 4,500 lives in a refugee camp of 11,000 people than they would give to save the same 4,500 lives if the camp held 250,000 people. But this is not just a matter of big numbers. It happens at even the smallest scale.

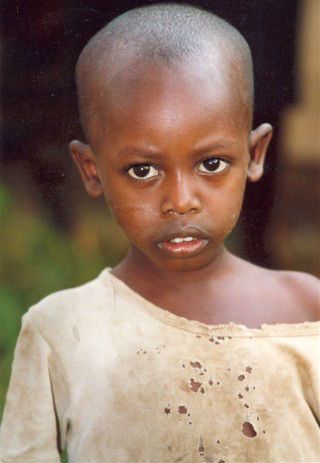

Imagine you are shown the picture and name of a child who needs your help to survive, and are then asked how much would donate to save that child:

Now imagine you are shown two children and told your donation can only save one of them:

Now how much do you give? These two scenarios are pretty close to identical. In both, your donation will save one child. But they don’t feel the same, do they?

Disturbing new research has found that people will donate more to save one child’s life if they see only that one child, and will donate less to save one child’s life if they are shown pictures of two children and told that their donation can only save one of them.

The good news is that this new piece of as-yet unpublished research—“Whoever Saves One Life Saves the World: Confronting the Challenge of Pseudoinefficacy”—has helped identify why this tragic irrationality occurs, an insight that might help us overcome the emotional drivers that dull our willingness to help others. What the research confirmed is what you might have assumed—that while helping feels good, knowing that you can’t help feels bad, and the bad feelings mute some of the good feelings that encourage you to help in the first place.

In a variety of scenarios, participants were asked how much they would give to save one child. They saw the child’s picture and name. Participants were also asked to rate, on a 0-100 scale, the "warm glow" they got from a donation—in other words, how good did giving make them feel? Sometimes they saw only the one child. Sometimes they saw two, or several, and were told that their giving could only help one. When they saw more than one kid, sometimes they were told specifically which kid would be saved and which wouldn’t. Sometimes they were only told that one kid out of the group would be saved, but not specifically which one.

In every case participants gave more to save one kid when they only saw one kid than when they also saw other kids who they would not be helping. And they gave themselves higher "warm glow" ratings when they donated to save one kid when they only saw one kid, than when they saved one kid out of two or more. It felt less good to save one kid when they knew there were others they could not help, than to save that same kid if he was the only kid the potential donors knew about.

This is both scary, and potentially encouraging: Scary, because when our subconscious feelings overpower a rational choice—to save one kid whether he’s one of one, or one of several—in real life that means that we aren’t helping others as much as we could. People we might be helping are suffering, or dying—and we are not doing the individual things we could to help address big problems like climate change—because of this foible in our cognitive make up.

But this research is potentially encouraging because, by understanding the emotional and psychological mechanisms that motivate us to give and help—or demotivate us from giving and helping—we can recognize how our feelings may be interfering with what makes sense, and at least try to avoid the mistake of not giving just because it feels like only a drop in the bucket. Focusing on the good we can do and trying to ignore the negative feelings from knowing what we can’t do everything, might encourage more of us give and help—and benefit more people and save more lives.

Aid organizations can use this research to frame their requests for our help in ways that are more likely to trigger the "warm glow" of helping, while avoiding anything that might trigger the negative feelings of not being able to help. In fact, one of the several studies within this research project tried just that, telling a group of participants that while their donations could only save only one kid out of the several they were shown, other people's donations would help save the others. When people learned that though their own donations couldn’t save everyone, that that didn’t necessarily mean the other kids would get no help, donations and self-described "warm glow" ratings went up.

The introduction of the research paper quotes a scene from the movie Schindler’s List. Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist who has saved hundreds of Jews from death in the Holocaust, takes off his lapel pin and says, “This pin. Two people. This is gold. Two more people. He would have given me two for it, at least one. One more person…and I didn’t! And I…I didn’t." That is the Drop in the Bucket feeling of not being able to help enough. But it didn’t keep him from helping. As the movie closes, Schindler is given a gold ring by the 1,100 people he did save, inscribed with the saying from the Jewish Talmud, "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.”

So, do you want to do a little good? Tweet or Facebook or Share this post. Or maybe just tell a friend about what you just learned—that we might do far more good in the world if we just try to fight back against the bad feelings we get from feeling helpless about what we can’t do, and stay aware of and enjoy the warm glow feelings we get from the good we can do.

Just sharing this little lesson could do a world of good.