Freudian Psychology

Totem and Taboo: The Life and Thought of Sigmund Freud

Freud in a nutshell.

Posted April 15, 2012

[Article updated 6 September 2017]

Understanding neurosis

People with a high level of anxiety have historically been referred to as ‘neurotic’. The term ‘neurosis’ derives from the Ancient Greek neuron (‘nerve’), and loosely means ‘disease of the nerves’. The core feature of neurosis is a high level of ‘background’ anxiety, but neurosis can also manifest in the form of other symptoms such as phobias, panic attacks, irritability, perfectionism, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Although very common in some form or other, neurosis can prevent us from living in the moment, adapting usefully to our environment, and developing a richer, more complex, and more fulfilling outlook on life.

Early years

The most original, influential, and polemical theory of the origins of neurosis is that of Sigmund Freud. Freud studied medicine at the University of Vienna from 1873 to 1881, and, after some time, decided to specialize in neurology. In 1885-86, he spent the best part of a year in Paris, and returned to Vienna inspired by neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot’s use of hypnosis in the treatment of ‘hysteria’, an outdated construct involving the conversion of anxiety into physical and psychological symptoms. Freud opened a private practice for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders, but eventually abandoned hypnosis for ‘free association’, which involves asking the patient to relax on a couch and say whatever comes into her mind (Freud’s patients were mostly women).

Later life

In 1895, inspired by the case of a patient called Bertha Pappenheim (‘Anna O.’), Freud published the seminal Studies on Hysteria with his friend and colleague Josef Breuer. Following the public successes of The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), he obtained a professorship at the University of Vienna and began to gather a devoted following. He remained a prolific writer throughout his life. Some of his most important works include Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Totem and Taboo (1913), and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). Following the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938, he fled to London, where, in the following year, he died of cancer of the jaw.

Birth of psychoanalysis

In Studies on Hysteria, Freud and Breuer formulated the psychoanalytic theory according to which neuroses have their origins in deeply traumatic and consequently repressed experiences. Treatment requires the patient to recall these repressed experiences into consciousness and to confront them once and for all, leading to a sudden and dramatic outpouring of emotion (‘catharsis’) and the gaining of insight. Such outcomes can be achieved through the methods of free association and dream interpretation, and by a sort of passivity on the part of the psychoanalyst. This passivity transforms the analyst into a blank canvas onto which the patient can unconsciously project her thoughts and feelings (‘transference’). At the same time, the analyst should guard against projecting his own thoughts and feelings, such as his disappointment in his own wife or daughter, onto the patient (‘counter-transference’). In the course of analysis, the patient is likely to display ‘resistance’ in the form of changing the topic, blanking out, falling asleep, arriving late, or missing appointments. Such behaviour is only to be expected, and indicates that the patient is close to recalling repressed material but afraid of doing so.

Aside from free association and dream interpretation, Freud recognized two further routes into the unconscious: parapraxes and jokes. Parapraxes, or slips of the tongue (‘Freudian slips’), are essentially ‘faulty actions’ that occur when unconscious thoughts and desires suddenly parallel and then override conscious thoughts and intentions, for instance, calling a partner by the name of an ex-partner, substituting one word for another that rhymes or sounds similar (‘I would like to thank/spank you’), or combining two words into a single one (‘He is a very lustrous (illustrious/lustful) man’). Parapraxes often manifest in our speech, but can also manifest, among others, in our writing, misreadings, mishearings, and mislaying of objects and belongings. Freud reportedly ‘joked’ that ‘there is no such thing as an accident’.

Models of the mind

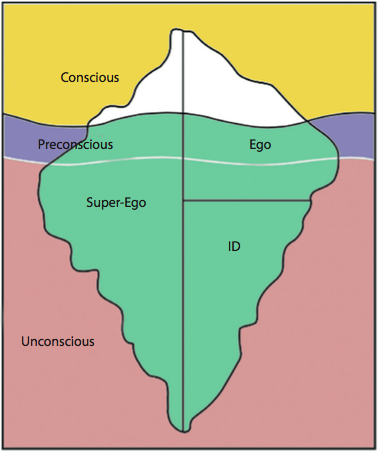

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud developed his ‘topographical model’ of the mind, describing the conscious, the unconscious, and an intermediary layer called the preconscious, which, although not conscious, could readily be accessed by the conscious. He later became dissatisfied with the topographical model and replaced it with the ‘structural model’, according to which the mind is split into the id, ego, and superego (see figure). The wholly unconscious id contains our drives and repressed emotions. The id is driven by the ‘pleasure principle’ and seeks out immediate gratification. But in this it is opposed by the mostly unconscious superego, a sort of moral judge that arises from the internalization of parental figures, and, by extension, of society itself. Caught in the middle is the ego, which, in contrast to the id and superego, is mostly conscious. The function of the ego is to reconcile the id and superego, and thereby to enable the person to engage successfully with reality.

For Freud, neurotic anxiety and other ego defences arise when the ego is overwhelmed by the demands of the id, the superego, and reality. To cope with these demands, the ego deploys defence mechanisms to block or distort impulses from the id, thereby making them seem more acceptable and less threatening or subversive. A broad range of ego defence mechanisms have since been identified and described, not least by Freud’s daughter, psychoanalyst Anna Freud (1895-1982).

Psychosexual development

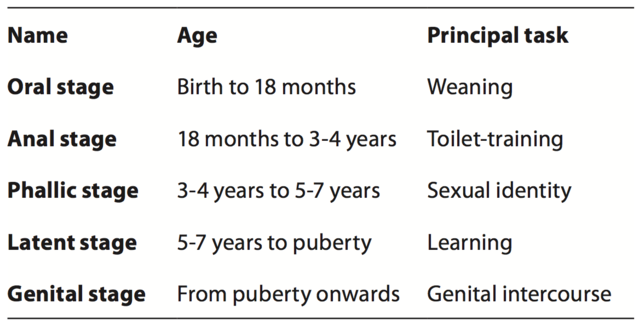

For Freud, the drives or instincts that motivate human behaviour (‘life instinct’) are primarily driven by the sex drive or ‘libido’ (Latin, I desire). This life-instinct is counterbalanced by the ‘death instinct’, the unconscious desire to be dead and at peace (the ‘Nirvana principle’). Even in children the libido is the primary motivating force, and children must progress through various stages of psychosexual development before they can reach psychosexual maturity. Each one of these stages of psychosexual development (except the latent stage) is focused on the erogenous zone—the mouth, the anus, the phallus, or the genitals—that provides the greatest pleasure at that stage. For Freud, neuroses ultimately arise from frustrations encountered during a stage of psychosexual development, and are therefore sexual in nature. Freud’s stages of psychosexual development are summarized in the table below.

The Oedipus complex

The Oedipus or Electra complex is arguably the most controversial of Freud’s theories, and can be interpreted either literally (as Freud intended it to be) or metaphorically. According to Freud, the phallic stage gives rise to the Oedipus complex, Oedipus being a mythological King of Thebes who inadvertently killed his father and married his mother. In the Oedipus complex, a boy sees his mother as a love-object, and feels the need to compete with his father for her attention. His father becomes a threat to him and so he begins to fear for his penis (‘castration anxiety’). As his father is stronger than he is, he has no choice but to displace his feelings for his mother onto other girls and to begin identifying with his father/aggressor—thereby becoming a man like him. Girls do not go through the Oedipus complex but through the Electra complex, Electra being a mythological Princess of Mycenae who wanted her brother Orestes to avenge their father’s death by killing their mother. In the Electra complex, a girl this time sees her father as a love-object, because she feels the need to have a baby as a substitute for the penis that she is lacking. As she discovers that her father is not available to her as a love-object, she displaces her feelings for him onto other boys and begins to identify with her mother—thereby becoming a woman like her. In either case, the main task in the phallic stage is the establishment of sexual identity.

Final words

Although much derided in his time and still derided today, Freud is unquestionably one of the deepest and most original thinkers of the 20th century. Despite the disdain in which doctors often hold him, he is, ironically, the most famous of all doctors and the only one to have become a household name. He is credited with discovering the unconscious and inventing psychoanalysis, and had a colossal impact not only on his field of psychiatry but also on art, literature, and the humanities. He may have been thinking of himself (he often did) when he noted that, ‘the voice of intelligence is soft, but it does not die until it has made itself heard.’

Neel Burton is author of The Meaning of Madness, The Art of Failure: The Anti Self-Help Guide, Hide and Seek: The Psychology of Self-Deception, and other books.

Find Neel Burton on Twitter and Facebook