Sport and Competition

The Olympics: 5 Things You Can Learn About Talent & Practice

Talent and practice are what make some athletes great.

Posted February 10, 2014

Guest post written by Michael Joyner, Professor of Anesthesiology at Mayo Clinic and blogger at Human Limits.

Elite sports competition generates a lot of discussion and debate. Much is bar stool yapping about who was the best ever but some is more serious about topics that include the role of talent and practice in elite performance. So, here are a few thoughts about talent and practice that you might ponder during the Olympics. They are gleaned from a longer e-mail discussion I had with Jon, David Epstein, Terry Laughlin, and Amby Burfoot.

1. More Than 10,000 Hours

There is a school of thought that all is required for exceptional performance is 10,000 hours of deliberate practice and there essentially is no such thing as talent. To test the 10,000 hour concept prospectively a guy named Dan McLaughlin comes to mind. Mr. McLaughlin has quit his day job as a commercial photographer to see just how good a golfer he can become with 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. After about 5,000 hours of practice he has a handicap of about plus 6 and his improvement seems to be stalling out. Top pros are routinely minus 4 or 5 on their home courses. At some level this little experiment shows us both the power and limits of deliberate practice. Dan McLaughlin is becoming a solid golfer and is now in the top 10 percent of people who actually post handicaps. However, to put it in perspective, about 15 percent of marathon finishers run under 3:30, so he is a long way from elite. Another example comes from Hayden Smith who is the cross country coach at Albion College. Smith was a good college sprinter who took up distance running in the 1970s, trained like a pro but “only” ran a 2:26 marathon after years of intense training. This is a 1/500 performance or better, but it is not a 1/50,000 performance like you see at the Olympics. The slippery slopes in the practice vs. talent discussion are what constitutes exceptional performance and perhaps a narrow definition of talent and how talent and practice interact.

2. Talent Identification Matters

For those who say talent matters perhaps the more important point is that talent identification matters. In this context, LoLo Jones is going to be all over the women’s bobsled coverage during the Winter Olympics. Jones is a superb hurdler who has transitioned to the role of bobsled pusher in the last couple of years to take advantage of her speed at the start of the race. This is nothing new and numerous track athletes have taken up bobsledding over the years. It is also another example of how talent matters and 10,000 hours of deliberate practice is not the only explanation for athletic greatness. A more systematic example of talent identification comes from Great British Rowing’s Start Programme which seeks to find tall people with a lot of aerobic power and turn them into rowers. This effort has been successful and resulted in a number of Olympic medals and World Champions for the Brits.

3. Opportunity Matters

During this Olympics you will not be seeing a bunch of Kenyans and Ethiopians dominating the cross-country skiing competitions. The obvious reason for this is that there is not a lot of snow in East Africa. The flip side of this is the role of roller-blades in expanding the talent pool for speed skating. So, the Winter Olympics is no longer dominated solely by people from cold climates as opportunities in traditionally cold weather sports globalize.

4. Who Specialized When?

In sports you find examples of early specialization and intensive practice, and there are also stories of people who sampled many sports early and specialized later. It is hard to generalize, but in some sports like women’s gymnastics there seems to be age related sweet spots for body size and strength to weight ratio that favor relatively young athletes, so early specialization is essential. In other sports there is evidence for later specialization in those who make it to the top and the evidence based recommendations are pretty clear:

“Some degree of sports specialization is necessary to develop elite-level skill development. However, for most sports, such intense training in a single sport to the exclusion of others should be delayed until late adolescence to optimize success while minimizing injury, psychological stress, and burnout.”

5. You Can’t Coach Desire

One thing that comes up time and time again in sports is the so-called “rage to master” concept. The idea is that very few people are both gifted in a given domain and also develop an interest in pursuing it like their hair is on fire. In some instances you hear about parents having to actually slow kids down and broaden their focus, and some coaches find the best way to instill discipline in their athletes is to paradoxically “kick them out of practice.” So, a lot of times it is the athlete who can’t get enough shaping his or her world vs. Helicopter parents burning their kids out.

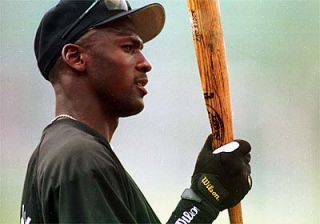

Most people can become very good at most things via focused practice. However like most complex human phenotypes elite athletic success is a combination of innate talent and environmental factors that include exposure, training, desire and culture. At age 30 Michael Jordan dabbled for a few years as a minor league baseball player. He was talented enough to be a really good baseball player but not close to the Big Leagues, and the summary statement by the scouts went something like this: “do I want MJ at age 30 – no, do I want him at age 17 – yes!”. In the final analysis, telling people it is all about practice or all about talent are both bad messages because both will only take you so far. Keep these things in mind as you watch the Winter Olympics.

Michael J. Joyner, M.D., is the Caywood Professor of Anesthesiology at Mayo Clinic where he was named Distinguished Investigator in 2010. His interests include: exercise physiology, cardiovascular regulation, autonomic regulation of metabolism, and the physiology of world records. His Human Limits blog can be found at http://www.drmichaeljoyner.com/.