Health

What Op Art Can Tell Us About Reading.

Subtle fixational eye movements may make reading uncomfortable.

Posted September 6, 2014

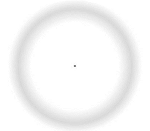

To look at something seems a simple act - just hold your eyes steadily on the target. This is called fixation. Although we spend about 80 % of our time in fixation, less is known about this important skill than different types of eye movements. Fixation presents a paradox. If you look at something without ever moving your eyes and retina, the target fades away. You can see this with Troxler’s effect. Make sure the circle in the figure below is 4 inches or more in diameter. Then, stare steadily at the center dot and, with time, the peripheral gray circle should fade away, then return, only to fade again.

Our visual system, indeed our sensory systems in general, do not like sameness. They respond only when something changes - so, as you stare at the central dot without intentionally moving your eyes, the large circle fails to keep activating your low resolution peripheral visual system. The circle disappears, but you see it again when you make a subtle eye movement, thus changing the visual stimuli that move across your retinal cells.

So, even when you are gazing steadily at something, your eyes are always moving. These movements are subtle, small jerks (microsaccades) that cover less than 2 degrees of visual space, slow drifts, and high frequency tremor. Microsaccades brought the gray circle back after it disappeared in Troxler’s illusion. Op art pieces, like Enigma by Isia Leviant or The Fall by Bridget Riley may have their bizarre effects in large part because of these subtle fixational eye movements.

When you look at Enigma for several seconds to a minute, you may start to see a streaming movement in the colored circles.

Enigma

A relatively recent study has shown that this effect is a result of your own microsaccades!

Fixational eye movements may also be involved in the undulations and shimmering you see in The Fall.

The Fall

The repetitive nature of the lines in the painting may create, via subtle eye movements, illusions of motion. These illusions excite the motion sensitive areas of your brain which may, in turn, stimulate even more eye movements so that the illusions build over time.

Strikingly, the illusions created by Riley’s The Fall resemble the illusions that many see in the simple image of black and white stripes that I discussed in the last post.

People who experience eyestrain when reading experience more of these illusions than people who read comfortably. This makes me wonder if excessive fixational eye movements may be partly responsible for reading discomfort. I bet people who experience a lot of illusions with the simple striped figure may find the op art pieces very uncomfortable to look at.

When tired or after looking at a computer for a while, I often experience a vibration, pulsing, shimmering, or jittering of letters while reading a book or computer screen. Looking at The Fall can really set off my visual system, creating wild line oscillations and undulations. All this may be due to my own eye movements during fixation especially because my fixational eye movements are not normal. I developed crossed eyes in very early infancy (infantile esotropia), and this disorder resulted in subtle, involuntary horizontal and rotary movements of my eyes called Fusion Maldevelopment Nystagmus (also known as latent nystagmus and manifest latent nystagmus). This nystagmus may have contributed to my problems as a child learning to read in school. When, at age 48, I learned to coordinate my eyes, fuse images, and see in 3D, thanks to optometric vision therapy, my nystagmus decreased. Edges and borders of objects appeared sharper and more well-defined, and I could read and do computer work for longer periods.

So, I wonder how many children or adults, even those without an obvious vision disorder, avoid reading because of overactive fixational eye movements. If they’ve always seen this way, they won’t know that their vision is unstable. Fixational eye movements are so subtle, they may go unnoticed by the eye doctor and may not significantly affect the ability to read the eye chart, but they certainly affect a child who hates to read.