Freudian Psychology

How to Tell Your Story or Write Up Someone Else's

The use of the narrator in Freud's five case histories.

Posted May 25, 2014

Reading Freud’s five case histories I could not help but recall the advice that John Coetzee, my fellow countryman and Nobel prize winner, once gave me when I told him I was writing an historical novel: Don’t stay too close to the truth he said looking severely at me. I promised to do my best.

It was, indeed, good advice. For the historical novel to work it needs the writer to select, to condense, and to reorganize the known facts. At the same time the writer’s imagination must embroider on them, filling in the spaces, finding what is unknown within the known, which is exactly what Freud seems to do by using the limited third person narrator. As Felix von Hardenberg has said, “It is in the failure of history that the novel is born.”

Freud, when not using the first person in his case histories, uses the limited third person which is convenient for him as a screen to hide the author, as in a modern novel, to make us think we are in the mind of the character or here the patient.

Freud takes a subtle approach. He chests his cards, so that we are never quite certain what lies in his own mind and what is in the patient’s. We are in a sort of middle distance, a no man’s land between the analyst and the analysand, an almost identical place taken by authors since Flaubert wrote “Madame Bovary” or H. James “What Maisie knew.” It is the ideal territory for the historical novel.

Freud works up to his revelations carefully. He uses the third person to delay, and to lead us to his conclusions, particularly in the later cases. He hides most skillfully behind the limited third person narrator, conjuring up the resistant minds of his patients with remarkable empathy and verisimilitude not unlike the great novelists. It creates the mystery and suspense which keeps us reading and which we find at the heart of each of these case histories.

Why is Dora so sick? Why is little Hans afraid of horses? Why is the Ratman obsessed with the story of torture a Captain in the army has told him? Why does the President Schreber think he can save the world if he changes his sex?

We read these texts as though immersed in a mystery story by Conan Doyle : Sherlock and his Watson, perhaps, though it is often the reader himself who plays the role of Watson, questioning at the right moment, showing skepticism. Freud himself compared his case histories to a short story rather than a scientific work. Indeed many have been used in novels, songs, and even made into films. Freud has provided us with the necessary inspiration: these stories with sufficient drama, high stakes, and convincing characters who draw the readers in through identification.

We can never be quite sure if we are being told the whole truth, or even if such a thing is important. Freud, here, might be likened to an unreliable narrator in his own text constructing someone else’s story, someone whom we see through the lens of the doctor’s desire to prove his new and startling ideas.

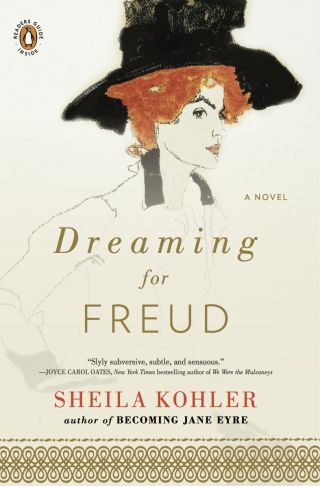

Sheila Kohler is the author of many books including the recent Dreaming for Freud.