Child Development

The Shadows of Our Mothers

My resemblance to my mother is more than skin deep.

Posted October 30, 2013

At a recent haircut appointment, I overheard an attractive teenage girl explain to her stylist, as she gazed at her reflection in the mirror, “I don’t want to look like my mom.”

She spoke in a flat, faintly annoyed tone, as if she were merely stating the obvious about the type of cut she wanted. But her remark produced in me an immediate, visceral tangle of emotions.

I sympathized with the girl’s mother, who was sitting just a few feet away and must have heard her daughter’s cold remark. I identified with the girl, who so emphatically wanted to distance herself from her mother. And I felt a stab of remorse for having had those same feelings at that girl’s age, and for many years thereafter. For decades, the last person I wanted to look like or be like was my mother.

When I was growing up, my mother terrified me much of the time. She often seemed angry and on edge. Tension appeared to emanate from her in nearly visible waves and, when the frequency was especially high, I learned to keep my distance. My father seemed the calmer, more rational parent. I thought he understood me and the workings of my mind in ways my mother never could. If someone had asked the teenage me which parent I preferred, I would have picked my father.

In high school, however, my priority was not analyzing my relationship with my parents. What I wanted was to put a sizable distance between me and the small town where I grew up. I escaped to college in a big city 100 miles away and, while I returned home often for visits, I vowed I would never live in the area again. Since neither of my parents had grown up there, or even in that region of the country, it never occurred to me that I might hurt their feelings. My perspective was that they had been stranded there by the unfortunate circumstance of my father’s job; I reasoned that, if they could, they would skip town, too.

On one of my visits home a few years after college, I said something, now forgotten, to my father that prompted him to respond in a tone of mild exasperation, “Oh Susan, you’re getting to be more like your mother every day!” He paused a moment before adding, “And she’s getting to be more like her mother!”

I remember being puzzled by his comment, but not puzzled enough to ask him about it. Perhaps I felt he was so far off base that to challenge him would be pointless. Still, I filed his observation away, in a mental folder I might have labeled, “Could this possibly be true?”

And then, while I was still in my 20s, my father died suddenly, felled by a massive stroke. Now I no longer had a choice between the parent I felt understood me best and the other parent. There was only one left, and it gradually dawned on me that perhaps I should find a way to understand her better.

Over time, I learned that my mother had been close to her father, a gentle man with a dry wit who owned a clothing store in her Vermont hometown and managed a theater that booked out-of-town talent such as John Philip Sousa. My mother’s mother had a sharp tongue and was sparing with praise. As my mother’s younger sister said to me recently, “Mother was more critical than she was kind.” In the classic Irish way, my grandmother’s favorite was her handsome first-born—her only son. In their mother’s eyes, the three beautiful daughters who followed—of whom my mother was the middle daughter—could never be the equals of their brother, either in childhood or as adults.

And yet, after she married and had children, my mother dutifully returned from Pennsylvania to Vermont each summer with her family to spend several days with her parents, and then, after her father’s death at 90, her widowed mother. Showing off the grandchildren (my brother and me) was the point of these visits; with our births, my mother’s stock rose somewhat in her mother’s eyes.

My father ran interference on the Vermont trips, breaking the ever-present mother-daughter tension with his own gentle wit. This in itself was a family miracle. My grandmother had so opposed my mother’s choice of a husband that she refused to attend their wedding, forcing my grandfather to take the train from Vermont to Philadelphia by himself for the ceremony, which was held at the home of my mother’s beloved older sister. But over time my father won over my grandmother; after she grudgingly accepted him, she came to adore him. Still, the tension between my mother and her mother never fully abated, and it remained unresolved at the time of my grandmother’s death at 91.

On one visit home years after both my grandmother and my father had died, I was standing beside my mother at her kitchen sink when she said something, then stopped herself quickly and exclaimed, in tones of horror, “Oh, I sound just like my mother!” In an exquisitely misguided attempt at sympathy, I replied swiftly and without thinking, “Don’t you hate that?” Luckily for me, my mother completely missed my inadvertent insult, so overwhelmed was she by hearing her mother’s tones coming out of her mouth.

True to my high school vow, after college I became something of a wanderer. I lived in Buffalo, Brooklyn, Manhattan, central New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and Honolulu, returning home for periodic visits and keeping in touch between visits with Sunday phone calls. Even my father’s death didn’t cause me to change my ways; I moved to Honolulu five years later. But my wandering came to an end when, four years after my mother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, she entered a nursing home. To help my brother take care of her, I packed up my things and returned from Honolulu to the area I had left behind so many years before.

Defying the odds and her doctor’s predictions, my mother lived for six and a half years in the nursing home. I visited nearly every weekend, often joined by my brother and his two boys. I talked to my mother by phone between visits, and I took care of her wardrobe so she could remain stylish even as her body failed her. I pushed her wheelchair on our "walks” down the sunlit corridors of the nursing home or—my fresh-air-loving mother’s preference—outside around the nursing home grounds or on the paths of the gracious municipal park next door.

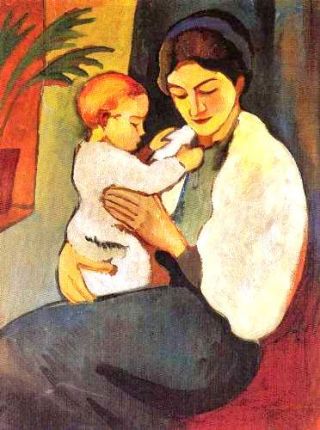

On our excursions, we would often encounter other daughters with their mothers. I could clearly see the mother-daughter resemblance in these pairs; it was as if the daughters were pushing the old, feeble version of themselves in some strange, stylized wheelchair ballet choreographed by Samuel Beckett. I realized with some surprise that I must look as much like my mother as these women looked like theirs, and that my mother and I were dancers in this poignant ballet, too.

In these last years together, my childhood fear of my mother dissolved, replaced by sympathy for the struggles she had had—as the daughter of a sharp-tongued, distant mother; as a wife and mother trying to negotiate the unfamiliar, often unforgiving landscape of post-World War II suburban America; and as a woman widowed suddenly at 63. As her Parkinson’s disease worsened, we became staunch allies in our fight against this implacable, relentless foe. Occasionally she would talk about her past, but much of our time together was spent simply negotiating the difficult present in which she existed.

It wasn’t until after my mother died, six days short of her 90th birthday, that I finally came to realize just how much like her I am. I put together her obituary for the local papers, following the single instruction she had given me a few years before: “When you write my obituary, don’t say that I just lived here.” At the same time, my brother made a touching video of her life that he showed at the lunch after her funeral.

In these tributes, the parallel lines of our lives became as clear as train tracks in the snow. My mother left home at age 21 with $100 in her pocket and a one-way train ticket to San Francisco, and she never returned to her hometown to live. She traveled extensively before she married; wanderlust was in her soul. She lived in Manhattan, Los Angeles and San Francisco, which became her favorite city. She joined the Red Cross during World War II and was posted to the wilds of western Canada. She loved music. She loved reading and writing. She loved being outside. The more similarities I saw, the more humbled I became.

Recently I joined Facebook and found a dear friend who had known my parents when I was young and whom I have not seen in years. After seeing my photo, he wrote to me, “You are looking more and more like your beautiful mother!”

He gives me far too much credit, but still I am grateful for his observation. Even now, four years after her passing, I miss my mother every day. But it comforts me to know that, in some ineffable way, she remains as close as my reflection in the mirror.

Oh, and the teenager in the salon? After her haircut, I happened to see the girl and her mother leave the salon and walk together to their car. Except for her slender teenage figure and her flawless teenage skin, that young woman was as close a copy of her mother as Nature can produce. If I ever see her again and have the chance to tell her that, I expect she might regard me with silent teenage contempt or, at the very least, indifference. I only hope she has enough time with her mother in the years to come to realize what a gift that resemblance can be.

Copyright © 2013 By Susan Hooper