Happiness

How Can a 16-Hour Day Be Optimized For Maximum Happiness?

Analyzing the hell out of awesome data to uncover the perfect day

Posted June 30, 2014

One of the hot trends in psychology is to capture daily life as it is directly perceived from one moment to the next, allowing insights into the links between the content of people's minds and what they are doing in the external world. Instead of asking someone how they tend to behave or feel across time and space (which is typical with a global survey), experience sampling researchers collect information in real-life situations over time. From this rich data, we can reconstruct what contributes to suffering and what contributes to well-being. In 2004, nobel-prize winner Daniel Kahneman and his impressive colleagues, examined a single day in the life of 909 women employed in Texas.

The methodology is worth detailing as it offers opportunities that global questionnaires or behavioral observations in a laboratory simply cannot offer. In their Day Reconstruction Method, Kahneman asked people to write a short diary about the previous day by (1) listing 4 to 5 episodes or scenes that captured the crux of their day, (2) documentating how long each episode lasted and (3) answer questions about each episode starting with the earliest. These questions included checking off boxes about what they did (playing the didgeridoo? eating a fried oreo at a carnival?), who they were with (step-mother's boyfriend's brother?), and how they felt (bored? confused?). From these juicy details, we learn about which activities are linked to the most positive emotions, the least negative emotions, feelings of competence, and how much time is spent doing things that bring the greatest net happiness (positive emotions - negative emotions). More about this initial study can be found here.

This morning I read about two economists who returned to this 10 year old dataset. They wanted to uncover the best way to create the perfect day–optimizing 16 waking hours for the greatest well-being. They used sophisticated logarithmic, inverse-quadratic, and hedonic utility functions that I will not detail here but you can find in the original article. What is important is that they considered two psychological factors that influence our ability to exploit potentially rewarding opportunities.

First of all, even the most pleasurable activity has a decreasing marginal utility. That is to say that the joy we get out of the first hour of shopping is likely to be greater than during the fifth or sixth hour. Second, an inverse effect closely linked to the first problem is that certain activities are attractive because we do them so rarely. Scarcity can therefore be expected to be a central feature of why we enjoy intimate relations more than work. (p.211, Kroll & Pokutta, 2013).

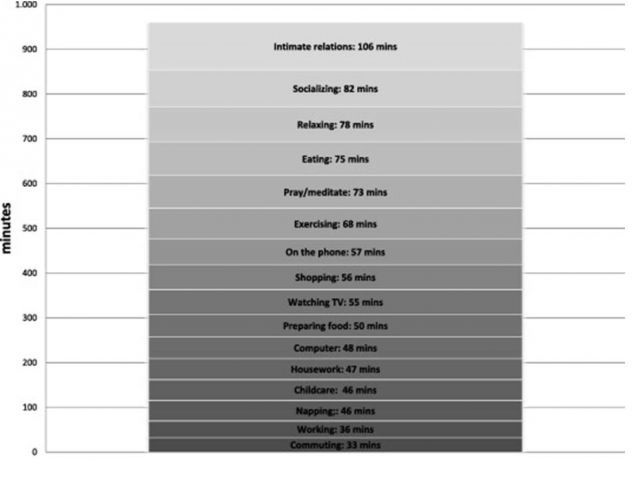

When the consumption of another tablespoon of lobster bisque or an additional minute of baby tickling has no change on our well-being, this is the saturation point or the point when the usefulness of an activity has reached its maximum. If the goal is to optimize a given day, then it is at these critical junctures that we must abort and move on to something else. Using mathematical formulas, we can account for the economic law of diminishing marginal utility and construct the "perfect day". That is exactly what these economists did with the data from 909 employed women from Texas. Here is a 16 hour day schedule perfectly optimized for maximium happiness with each activity listed in minutes:

And there you have it.

A lot of sexual activity. Much more than mere mortals such as myself can handle. A lot of time where we chill out and appreciate ourselves and the world around us, often with a killer book in hand. A lot of time in quiet contemplation, regardless of the belief system that guides you. One really good phone conversation. One well-selected television show. A nice siesta at 2:13pm in the afternoon. And minimal formal work with a small commute to get there and back.

Keep in mind, this so-called "perfect day" is based on data from 909 women working in a textile factory in Texas. This may explain the small marginal utility of happiness derived from work (as this job does not encapsulate the american dream of fulfillment). Also note that the goal of this study was to figure out how to construct a perfect day without consideration of aspirations that last longer than a day, week, or even years.

Despite these caveats, you can use these findings as a benchmark. If you closely examined how your time is allocated in a given day, what would it show? How much of time is generating happiness? meaning in life? personal growth opportunities? positive relationships with others? autonomy? generativity? If not, perhaps its time to become more consciously aware of how you spend your time and energy, the most valuable of currencies. Perhaps its time to ensure your needs get met instead of merely making it through one day to the next.

Start taking action. Don't dismiss the importance of your own unfulfilled needs. You don't have to choose between a selfish and unselfish life. Live in a way where your needs and the needs of loved ones co-exist peacefully.

Dr. Todd B. Kashdan is a public speaker, psychologist, and professor of psychology and senior scientist at the Center for the Advancement of Well-Being at George Mason University. His new book, The upside of your dark side: Why being your whole self - not just your “good” self - drives success and fulfillment is available from Amazon , Barnes & Noble , Booksamillion , Powell's or Indie Bound. If you're interested in speaking engagements or workshops, go to: toddkashdan.com