Psychology

How High Is Your Horizon?

Landscape drawings reflect cultural habits of thought.

Posted October 17, 2014

Note: This post was written by Steven Jackson.

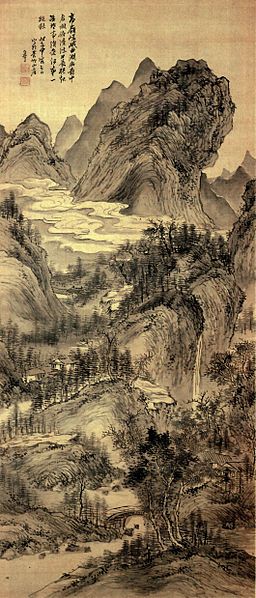

“Autumn Landscape” by Kinoshita Itsuun

Not long ago, on an ordinary school day in Japan, a team of researchers crammed themselves into a first-grade classroom. They passed out art supplies to the students, along with some simple instructions: Draw a landscape, including at least a house, a tree, a person, and a horizon. The children had 30 minutes to complete their drawings.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the same scene played out in a Canadian classroom. The teacher halted the lesson and the children dutifully set to work on their landscapes. Exactly 30 minutes later, the researchers gathered the artwork and left. After the classroom visit, they analyzed the drawings with an eye for one detail: Where was the horizon line? They repeated the artwork assignment for students in grades 2 through 6, always carefully measuring the placement of the horizon on the page.

These scientists were not the first to be fascinated by horizon lines. Several years ago, a team of cross-cultural psychologists, led by Takahiko Masuda, analyzed hundreds of paintings from East Asian and Western cultures between 1500 and 1900. They found that, in landscape art, East Asian paintings consistently had higher horizons.[1]

Why do psychologists care about horizon lines in art? To answer that question, we need some context.

Research over the last two decades has revealed systematic cultural differences in cognitive processes across cultures—and some of the most striking differences are between adults from Western and East Asian cultures. Westerners tend to think more analytically, while East Asians think more holistically. Analytic thinking is marked by logical reasoning, a belief that individuals and their attributes are the primary cause of events in the world, and a focus on objects in the foreground of a visual scene. Holistic thinking, on the other hand, is characterized by dialectical reasoning, a belief that events are caused by external forces beyond the control of individuals, and a focus on the background elements of a visual scene.

This is where art comes in. The placement of the horizon in a piece of art tells us a lot about the culture in which that art was made. If the horizon is high on the page, the field of information is deep, and there’s ample room for contextual details in the frame. This kind of visual layout reflects a holistic cognitive style, which is more common in East Asian cultures. If the horizon is low on the page, there’s less background space in the frame, and more of the page is taken up by one or two objects in the foreground. This kind of visual layout reflects the analytic style that is more common among Westerners.

“The Golden Gate Looking West” by John Ross Key

When the same researchers who analyzed all those classic paintings asked adults to draw landscapes, they found that East Asians tended to draw their horizon lines higher than Westerners—about 19% higher, to be precise.

But there’s a problem here: Most of the cross-cultural research on cognitive style has used young adults as subjects. As a result, we don’t really know how early in the lifespan these differences emerge. That’s why the researchers were collecting art from grade-schoolers in Japan and Canada. They wanted to know if these cognitive styles are learned later in life, or if they are present from a very young age.

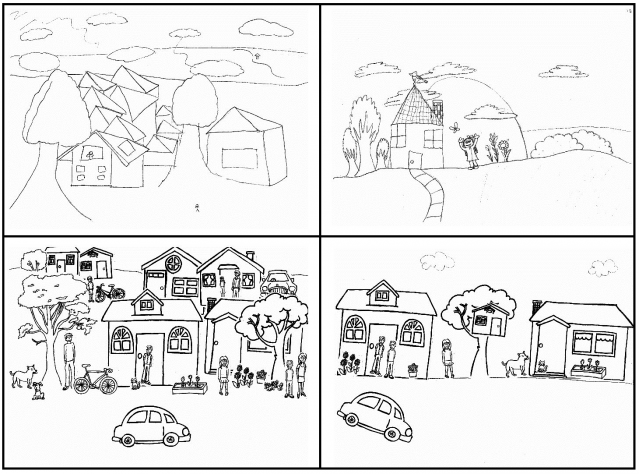

When they analyzed the children’s artwork, they got their answer. Starting in the second grade, Canadian children drew their horizon lines significantly lower than Japanese children did. (First-graders in both countries didn’t understand the concept of the horizon at all; their lines were all over the place.) To ensure that drawing ability did not influence the results, the researchers conducted a second study in which the kids used pre-made collage items to create a landscape.

Top: Drawings by Japanese (left) & Canadian (right) children. Bottom: Collages by Japanese (L) & Canadian (R) children.

In both the drawing and the collage tasks, the results were the same. Once children understand what a horizon is and how it relates to perspective, they begin to make art that is consistent with their culture: Japanese kids make art that is more context-rich, while Canadian kids make art that is more focused on singular objects in the foreground.

These studies remind us that works of art are more than just pretty pictures. They’re cultural products that reveal diverse ways of thinking and moving through the world.

Sources:

Masuda, T., Gonzales, R., Kwan, L., & Nisbett, R.E. (2008). Culture and aesthetic preference: Comparing the attention to context of East Asians and Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1260-1275.

Senzaki, S., Masuda, T., & Nand, K. (2014). Holistic versus analytic expressions in artworks: Cross-cultural differences and similarities in drawings and collages by Canadian and Japanese school-age children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(8), 1297-1316.

[1] By “East Asian,” cross-cultural psychologists usually mean Japan, China, and Korea. “Western” usually means the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.