Bias

What Color Is Racism?

On the crossroads of race, sex, and skin tone: Black women and colorism

Posted November 22, 2012

What is Colorism?

Although most of us have a general understanding of racism, few consider the impact of skin color apart from race. Colorism is a very specific form of discrimination based on the shade or tone of one’s skin. People may be discriminated against because of their perceived membership in a particular ethnoracial group (racism), because the shade of their skin (colorism), or both.

Origins of Colorism in America

In the United States, discrimination based on skin tone dates back to the chattel system of slavery, where skin color was often used as the basis for the division of labor (Hunter, 2002). Darker-skinned slaves were typically given work in the fields and had more physically demanding jobs, whereas lighter-skinned slaves were given more desirable positions, such as cooks or maids. The lighter-skinned slaves were usually a result of racial mixing, as it was common for slave owners to sexually abuse their slaves. These divisions promoted the notion that darker-skinned Blacks were inferior, evidenced by the fact that lighter Blacks were considered more attractive, intelligent, and trustworthy by their White masters.

Although slavery ended over 150 years ago, the effects of this mentality remain today. Research shows that darker-skinned African Americans are disproportionately disadvantaged in many areas. For example, one study found a hiring advantage for lighter-skinned African Americans, even when the resumes of dark versus light skinned applicants were identical (Harrison & Thomas, 2009).

Colorism and Beauty

These biases are particularly salient for African American women, as the American ideal of beauty is primarily Eurocentric. Women who have lighter skin, straighter hair, and more European facial features are preferred over those features considered more historically African. Thus, many Black women wrestle with their physical appearance and whether they meet the dominant culture’s female ideal. They may straighten and lighten their hair to be closer to the Eurocentric standard. Black women put more time and energy into their physical appearance, which may be in part to compensate for being considered less attractive than White women.

Example of Colorism and Stereotypes in the Media

Angela Bassett is considered one of the most talented African American actresses of all time, having received multiple NAACP Image Awards and several nominations for Emmy Awards. However, she has yet to receive an Academy Award, despite her electrifying performance in What’s Love Got to Do With It, where she portrayed recording artist Tina Turner (although it did garner her a Golden Globe). In 2000, Bassett turned down the lead female role in Monster's Ball, because of the script's sexual content, where she would have played a poor, abusive, single Black mother, who engages in a highly sexualized relationship with her deceased husband’s executioner.

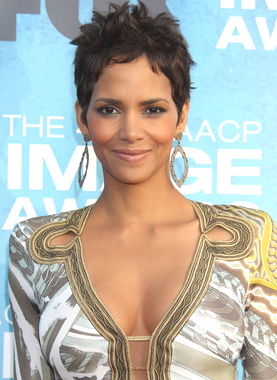

I have nothing but respect for Bassett’s decision to reject this unsavory Black female stereotype, despite the fact that the role earned the fair-skinned Halle Berry the Academy Award. This is a good illustration of how our society rewards both lighter-skin and conformity to stereotypes. Honoring Berry for this role sends the unspoken message that lighter-skinned Black women are more talented and beautiful, despite that Berry is an arguably inferior performer to Bassett who, in my opinion, remains underappreciated.

Black women with light skin, therefore, can have a resume that depicts a lower degree of competence than that of a darker-skinned Black female, because their light skin grants them a level of competency that is not similarly awarded to a darker female. Thus, it is unsurprising that lighter-skinned Black women have higher salaries than equally qualified Black women with darker skin (Hunter, 2002).

Colorism Affects Everyone

Because colorism is widely pervasive in our society, people of all ethnoracial groups are vulnerable to these beliefs, and may, in turn, perpetuate colorism upon others. One study found that Black women were rated as more attractive by other African Americans if they had lighter skin – and the lighter the better. However, the same effect was not evident for Black men (Hill, 2002).

Although darker-skinned women receive the brunt of colorism, lighter-skinned Black women are sometimes victims of reverse color bias, particularly from other African Americans who may be resentful of the unfair advantages accorded to their fairer sisters.

For African American women to be psychologically healthy, they must recognize the reality of both racism and sexism in their lives, and the associated stereotypes – including the expectation to placate and serve others, inferiority status, and sexual promiscuity. Additionally, they must be aware of the social systems of rewards and punishments associated with skin tone. Lighter skin continues to be associated with attractiveness, intelligence, competency, and likability, whereas those with darker skin may be frowned upon by Blacks and Whites alike. Darker women may therefore experience lower self-esteem, greater frustration, and may be at higher risk of negative psychological outcomes.

Challenge Yourself

It’s important that we continually challenge and illuminate these harmful social biases. The more attention we can bring to invisible systems of prejudice, the greater our chances of repairing America’s racial problems and promoting a society that can appreciate the beauty and ability of all women.

References

Harrison, M. S., & Thomas, K. M. (2009). The Hidden Prejudice in Selection: A Research Investigation on Skin Color Bias. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 1, 134-168.

Hill, M.E. (2002). Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference? Social Psychology Quarterly, 65(1), 77-91.

Hunter, M. (1998). Colorstruck: Skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Sociological Inquiry, 68, 517-535.

Hunter, M. (2002). “If you’re light you’re alright”: Light skin color as social capital for women of color. Gender and Society, 16(2), 175-193.

Thomas, A. J., Hacker, J. D., & Hoxha, D. (2011). Gendered Racial Identity of Black Young Women. Sex Roles, 64, 530-542.