Personality

Selfless Service, Part II: Different Types of Seva

Selfless service can be more than just feeding the hungry and nursing the sick.

Posted June 19, 2013

In my previous blog post I examined the Indian concept seva, often translated as "selfless service." I spent much of that post exploring whether it is actually possible to do service (or do anything for that matter) completely selflessly—that is, without expecting some kind of personal benefit, even if the benefit is just feeling good about yourself. I concluded that people may in fact help others without consciously thinking much about the benefits they might receive in return, but that those who help others must in fact benefit in some way. As I put it, "Someone who only gives and never receives from others will soon be used up and die."

Indeed, research indicates numerous benefits to those who engage in selfless service, including reduction of emotional disturbance, greater longevity, stress reduction, improved morale, increased self-confidence and self-esteem, better health and pain reduction, and greater overall happiness. According to Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, the joy of giving is far more exhilarating than the joy of getting, and can be likened to a thrill or high. But there is sort of a paradox noted by the authors of research on volunteering, "It is reasonable for people to volunteer in part because of benefits to the self, however, our research implies that, ironically, should these benefits to the self become the main motive for volunteering they may not see those benefits." In this particular study, those who volunteered for personal gain or self-growth suffered the same mortality rates as those who did not volunteer at all.

So, if you expect to obtain better physical and psychological health from engaging in volunteer work, forget it. That's the wrong motive. You must be motivated by selfless compassion, not the desire for self-improvement, in order to experience health benefits.

After I accepted that engaging in service selflessly—that is, helping someone else out of compassion, without a conscious thought of personal benefit—is not only possible, but necessary for increasing your own health, I found myself pondering another question: "Is selflessness something I can acquire through certain practices, or is one's degree of selflessness a relatively stable aspect of one's personality?" As a personality psychologist, my automatic hunch was the latter. In fact, when I thought about traditional examples of seva ("Feed the hungry, nurse the sick, comfort the afflicted, and lighten the sorrow of the sorrowful. God will bless you. Clothe the naked. Educate the illiterate. Feed the poor. Raise the down-trodden"), I immediately thought of the Social personality type described by the greatest vocational psychologist of all time, Johns Hopkins professor John L. Holland. The following is a description of the Social type from the Johns Hopkins Career Management Program:

Social individuals are humanistic, idealistic, responsible and concerned with the welfare of others. They enjoy participating in group activities and helping, training, healing, counseling or developing others. They are generally focused on human relationships and enjoy social activities and solving interpersonal problems. Social types seek opportunities to work as part of a team, solve problems through discussions and utilize interpersonal skills but may avoid activities that involve systematic use of equipment or machines. Because they genuinely enjoy working with people, they communicate in a warm and tactful manner and can be persuasive. They view themselves as understanding, helpful, cheerful and skilled in teaching but lacking in mechanical ability. The preferred work environment of the social type encourages teamwork and allows for significant interaction with others. Typical social careers include teacher, counselor and social worker.

Clearly, someone who is a Holland Social type has exactly the right constellation of personality traits that would incline him or her toward selflessly serving others. Social types are warm, friendly extraverts who are naturally concerned with the welfare of others and who genuinely enjoy helping people. They find feeding the hungry, nursing the sick, comforting the afflicted, etc. intrinsically rewarding. They often enter careers in human services, not for the money (salaries in the human services are much lower than salaries in business, computers, engineering, finance, and science), but because they simply enjoy helping people.

Try as I might, I could not help feeling a little envious of Social types. True, they will rarely be rich, but they are likely to be healthy and happy, and isn't that more important than having a lot of money? Furthermore, they get along well with other people, they are praised by society for their selfless service, and, if the gurus, swamis, and avatars are correct, they are most likely to achieve enlightenment and salvation. How does someone who is not a Social type receive these blessings?

I actually asked Google this question by typing "How do I become selfless?" into a search box. The first item that turned up was a wiki with a five-step plan for becoming selfless. Follow the link if you are curious. I also found someone who, like I, wondered if it isn't selfish to want to be selfless. Through further searching, I found that those who advocate seva do not recommend trying to become selfless by grudgingly volunteering for service. You must be in a selfless frame of mind before engaging in service, or your efforts may backfire.

Sathya Sai Baba lists as prerequisites for seva the following qualities: a pure heart, charity, love, selflessness, and a fervent attitude. Sai Baba devotee Phyllis Krystal writes in Taming Our Monkey Mind, "Service, whether to family members or others, should be undertaken for the right reasons and not with any ulterior motives in mind, for that would curtail its effectiveness. To be free from ego it should flow out of deep compassion for the pain, hunger, feelings of rejection, loss, or any other problem from which either an individual or a group is suffering. Only then will it benefit the one who serves as well as those receiving the services. Therefore, Care needs to be taken against deciding to engage in a particular service in order to feel important or worthwhile, to gain recognition, gratitude, or any other reward from the beneficiaries, or for spiritual or personal gain of any kind" (p. 39).

Social types already have the right attitudes for practicing seva. But what about the other five Holland types who lack the deep humanitarian concern of the Social type. Is there any way for them to practice seva?

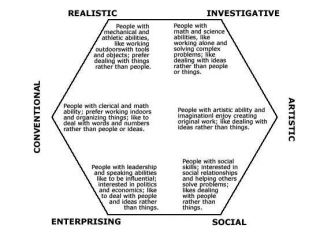

Before delving into this question, I need to share some information about the Holland personality types. First, here is a thumbnail description of the other five types: Realistic (asocial, mechanically inclined individuals who like to work with their hands); Investigative (intellectual puzzle-solvers who enjoy scientific research); Artistic (creative, sensitive individuals who like to express themselves through writing, drama, music, or visual arts); Enterprising (assertive, dynamic leaders who enjoy directing and managing other people), and Conventional (meticulous, methodical people who find satisfaction in following routines and maintaining order). If you would like to assess your own vocational-personality interest type, there is a free inventory on pages 9-10 of the Pennsylvania Career Guide.

As you might guess, only rarely can people be described in terms of one pure Holland type. More often a person will resemble one of the types most strongly but will also possess some traits of a second and even a third type. Holland therefore described people and work environments in terms of a primary, secondary and tertiary type. For example, a combination of the Investigative and Artistic types describes intellectuals in general. People who also have a Social component to their personality (IAS, AIS, ASI, ISA, etc.) are often drawn to the social sciences or humanities. I chose this example because my own type is IAS/R (predominantly I, secondarily A, with S and R tied for third.) Many university career and advising centers (for example, the University of North Florida) provide charts that link Holland codes with fields of study to help people choose careers compatible with their personality type.

While mowing grass at a summer job in my college days, I had a supervisor who was fond of saying, "It takes a lot of different kinds of people to have a world, and we sure got 'em!" John Holland always stressed equal value of all six personality types, a point with which I heartily agree. In his theory, our diverse interests, values, talents, and abilities draw us toward specialized vocational roles, all of which are equally necessary for a viable society. The equal importance of all six vocational-personality types is nicely captured in the famous Holland hexagonal arrangement of the types.

The hexagon, which is essentially a circular shape, does not rank any of the types as higher or more important in any sense. All have an equal place at the circular table. The hexagonal structure represents similarities and differences among the types; types that are immediately adjacent to each other share some traits while types on opposite sides of the hexagon are psychological opposites. For example, the Enterprising and Social types describe extraverted individuals who like to work with people. On the opposite side of the hexagon are the more introverted Realistic and Investigative types who prefer working with things and ideas, respectively, more than people. The Conventional and Artistic types define opposing but equally important roles in society: the conservative maintenance of order versus innovative exploration and creativity.

Every successful human society needs all six kinds of individuals. The extraverted Enterprising and Social types specialize in problems of human relations: leading and helping. The introverted Realistic and Investigative types specialize in the development and use of the group's technologies. The Conventional and Artistic types provide for both stability and creativity within the group. I believe that the six types have been equally important throughout the entire evolutionary history of human social organization, dating back to hunting-gathering times. As I once wrote: "Although Holland's model was designed to describe modern occupations, it can also describe social roles probably present near the beginning of our species' evolutionary history: hunters (Realistic), shamans (Investigative), artisans (Artistic), healers (Social), leaders (Enterprising), and lorekeepers (Conventional)."

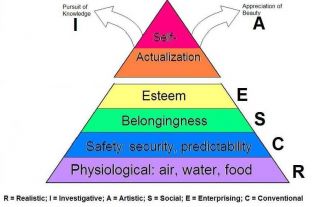

My commitment to the idea that all six Holland types are equally important is not shared by everyone. I once pointed out that Maslow's famous hierarchy of needs or values mirrors the Holland types in the sense that each Maslow need/value is of unique, central concern to each Holland type.

Realistic types work the physical environment with their hands to put food on the table; for them, Maslow's basic physiological needs are their primary concern. Conventional types crave the security and predictability and therefore organize their lives around safety needs. Social types thrive on friendly, helpful relationships and therefore care most about what Maslow called belongingness. By esteem, Maslow was referring to a need for respect, a need for others to look up to them. This is what Enterprising types hope to satisfy by the acquisition of power and resources. And, finally, Maslow's "higher" self-actualization needs such as the search for truth and beauty are the central concerns of the Investigative and Artistic types.

The pyramid-shaped hierarchy of needs implies a much different view of the relative importance of the six Holland types, even though he was writing before Holland proposed his hexagonal model of types. In Maslow's theories, there are "lower" or deficiency needs and "higher" becoming values. The lower needs are more basic and must be satisfied to some degree before a person can work on higher order concerns. Only a rare few individuals are self-actualizing because they are mired in more basic concerns. Although he did not brag about being self-actualizing himself, he was a self-admitted intellectual elitist, and his model clearly glorifies his own Investigative-Artistic intellectual personality.

But let's return to the Social type, who is most drawn toward selfless service. In Maslow's model, the ordinary Social type is nothing special, being situated only half-way up the pyramid. Maslow has written that his highest sort of person, the self-actualizing individual, cares about humanity, but only in a rather abstract way. His description of the self-actualizing person is one of a person (like himself) who is not particularly socially adroit and who does not enjoy getting down in the trenches, engaging in face-to-face assistance to the sick, poor, ignorant, and needy populace. As an intellectual, he would prefer to forward theories and ideas that might be helpful to humanity as a whole, while leaving to others the knitty-gritty helping.

The Holland hexagon, once again, does not place the Social type in a privileged position above the other five types. Social types play an invaluable role in caring for those who need help. But the other types also play invaluable, albeit different roles in society.

So, how is it that religious and spiritual traditions extol the virtues of selfless service over anything else a person might do in this lifetime? In what sense does volunteering to comfort a few sick individuals buy more spiritual currency than any other Holland-type activity? Realistic types build hospitals and medical equipment that serve thousands of individuals. Investigative types discover cures for diseases that reduce the suffering of millions of people. Artists write stories, perform music, and produce movies that bring joy to countless people who might otherwise be living drab, depressing lives. Enterprising types provide the leadership that directs the activities of all the other types. And the Conventional types are unsung heroes, gladly engaging in routines and repetitive activities that non-Conventionals might find boring, but are absolutely necessary to maintain everyday life. They are the custodians who take care of us all.

I first thought that religious people who say that selfless service is more spiritual, more important than any other activity, are simply myopically asserting that what they like to do is more important than what others like to do. As Social types, they glorify the value of selfless service, just as the intellectual Abraham Maslow glorified the value of truth and beauty. Then again, maybe I was just being defensive and envious.

What I finally decided that the work of any of the six Holland types can be seva, as long as the work is offered with intent of improving the human condition, without expectation of any kind of compensation or remuneration. Interestingly, as I was putting the finishing touches on this post, I ran across an article with exactly the same message, Anyone Can Do Seva! A Hindu American High Schooler's Serendipity Moment. The article provides many enlightening observations about seva, not the least of which is the following: " Seva is not a singular, but rather a multifaceted, concept. Many people think of Seva in a trite manner, believing it is simply the act of giving food or money to those less fortunate, or educating those who cannot afford an education. Of course, these are highly important aspects of Seva, but service can be done in many other ways." Each Holland type has gifts, strengths, talents, and abilities that can be offered as seva if employed selflessly.

Before signing off, I wanted to note that some, but not all, advocates of seva believe that you should serve according to the natural talents, interests, and inclinations embodied within your personality type. An example of a program that does assign seva based on unique abilities and interests is the Skanda Vale Seva Programme, which explicitly asks applicants to note special skills such as carpentry and plumbing so they can be matched to special seva assignments. But others believe that seva should involve activities outside the tendencies of your personality. In An Approach to Seva Yoga, Sannyasi Ratnashakti writes, "This artificial construct called personality is the illusion that the practice of seva yoga begins to dissemble and purify. Many times during the practice of seva yoga we are asked to do tasks that are not in accordance with our way of thinking or behaving. This creates an internal friction, as the limiting and illusory aspects of the personality are challenged and it is precisely at this point that the practice really begins." Similarly, in What is Seva, Savitri Louise Harkema writes, "I asked for a seva duty. I did not ask for a specific duty in an area where I may have an expertise or a duty that I would like to do. I was willing to accept whatever seva she asked me to do. I am open to a task or tasks without a personal preference or personal gain attached to it."

Yet another approach to seva is to find a population that suffers from a problem similar to one of your own, but to a greater degree. In Puja versus Seva, Barbara Pijan Lama Jyotisha writes, "One will see oneself reflected in their mirror rather quickly. . . . Only Seva can expose the blind spot. Works like a charm to solve one's own problem and helps others in the process."

Is selfless service (seva) possible? Yes, I think so. One thing is clear, though, "Seva is not a singular, but rather a multifaceted, concept." There are many kinds of seva, surely enough for the many different kinds of people it takes to have a world.