Humor

Writing a Life with MS

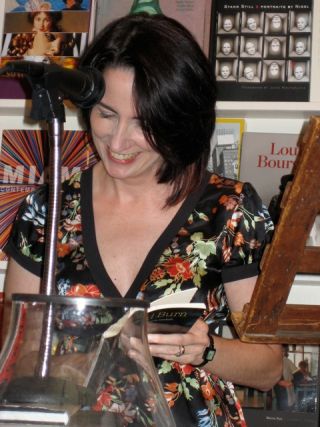

Soaring words help poet with MS adapt to her reality.

Posted January 10, 2013

Laurie Clements Lambeth is a successful poet. She turned to poetry when she was diagnosed with of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis at the early age of 17, and much of her output has focused on that particular challenge. Is she ever "grateful" for having MS? Not exactly -- but keep reading to the end.

Now 44, Lambeth earned an MFA and PhD in creative writing at the University of Houston, where she was awarded the Michener Fellowship and Inprint Fellowship, and where she teaches as an adjunct. Her work has appeared in many journals.Veil and Burn, her first book of poems, interspersed with prose fragments, was chosen by Maxine Kumin for the 2006 National Poetry Series.Veil and Burn was published later by University of Illinois Press.

Her resilience, her ability to adapt to a multitude of challenges, and her very articulateness, make for fascinating reading in her published work as well as in the interview below.

Q&A with Laurie Clements Lambeth:

Q: Laurie, isn't 17 early to get such a devastating diagnosis? How do you feel this affected your psychological development? It doesn't seem as though it slowed you down much achievement- or education-wise.

It was indeed an early diagnosis, but not so devastating. Today it would be classified as pediatric MS, which has gained recognition in recent years. Because I was a minor, the diagnosing neurologist invited my mother into his office while I waited in the hall. Then they brought me in. It was strange to have my mother know the name of my illness before I did.

To be honest, it was a relief to put a name to my symptoms. For me, 17 was the perfect age to be diagnosed. I hadn’t taken school very seriously up until then, didn’t understand the concept of homework, and figured I would be an artist, illustrator, or horse trainer anyway. In essence, since so many decisions are being made at that critical juncture between childhood and adulthood, I was able to restructure my expectations of myself and my future, and reconceptualize how I fit in the world. While it wasn’t mortality I was facing (I was assured by the diagnosing neurologist that MS is not fatal), I began to appreciate my life more. I knew there may be times when I might not be able to rely on my body, so I threw myself into studying during my senior year of high school and in college. The plan was to develop the mind. I didn’t know—or it wasn’t widely known or talked about then—that MS also can affect cognition, which has become a bit of an issue in my adult life.

I have met, heard of, or read about people who were diagnosed in their 30s, and it seems to have been a much larger adjustment for them. At 17 I was still forming an identity, and I settled into MS because I knew it would be my future, so I’d better get used to it.

MS actually did slow me down, but slowness is just time, isn’t it? MS—disability itself—is, to me, all about adaptation and adjustment. Rolling with the punches.There were indeed delays because in college and graduate school I took a reduced course load. In graduate school I often took incompletes in literature courses, and used summers to really dive into long papers.

As I began my last semester of coursework for the Ph.D, I developed optic neuritis, the one MS symptom I had feared the most, in my dominant eye. Searing pain accompanied every eye movement. Bright light burned. When I tried to read, letters would swim outside of themselves and blur.

I was lucky to be taking a creative nonfiction workshop with Mark Doty at the time, and a Romanticism class with another wonderful professor. They were kind and understanding. The creative nonfiction class gave me an outlet to explore in prose what I was currently going through, and in the Romanticism class I found a kindred spirit in Coleridge, whose work I read on giant, highly enlarged photocopies. People drove me to class. Friends read to me and sent me tapes. My husband read to me.

Q: Could you share a few words about the course of relapsing-remitting MS?

It’s strange. Every time, even when familiar symptoms occur, my body has remembered but was also surprised, as though hearing an echo from a great distance. I’m usually more curious than I am distressed about the flare-ups. There is, of course, a distressing moment now and again, but then I start thinking about it, and I become fascinated by how foreign my body is to others, and even to myself. MS has been part of my life so long that I have just sort of built around it, so to me it’s just life as an adult, as opposed to life in a 16-year-old body, which no adult really can claim anyway.

In my first eight years with MS there were no flare-ups, only fatigue and occasional numbness. Soon after, I would have an exacerbation every year or two. Back then, when a flare-up would subside after maybe 10 weeks, it would kind of feel like a miracle, because all of a sudden I could walk normally. Another reminder of how precious mobility can be. Nowadays, it’s harder to go into remission, something I sometimes have to seek help for. Physical and Occupational Therapy have retrained my brain a number of times, and strengthened my muscles and coordination.

Q: If you could change one (or two) things about the public's perceptions of those facing challenges analogous to yours, what would you choose?

MS varies widely from person to person. We don’t all “end up in wheelchairs,” but even so, wheelchairs are not necessarily devices people are “bound” to. The charts by which disability is measured usually track decline with a cane, then a walker/rollator, then a wheelchair, as though these symbols are things to be avoided, worst case scenarios. But mobility aids help us go further, walk more smoothly, balance, or just get across campus or around the grocery store.

Similarly, if a person with a chronic, disabling illness is not using a mobility device, it doesn’t automatically mean that he or she is without symptoms. “But you look so good!” is such a common phrase that the National MS Society has a pamphlet with that very title. Looks can be deceiving.

Q: With any chronic disease, there are emotionally down days. How do you handle yours?

I talk it out with my husband or mother or best friend. At some points I have cried. Sometimes I write, although the writing usually comes after turning the experience around in my mind a while. I look for meaning in it, what it might suggest about something larger than myself. I analyze. I hug my dog. And I get on with things.

Q: Would you share a little with us about your creative process?

I don’t write very regularly, or as often as I’d like. When I’m teaching my mind is in another zone, but vacations and lucky days when a sentence enters my mind and I just can’t stop myself from writing, I am lucky and I write. I’ve given into the impulse to write more recently. Physically, it has also proven difficult: in December 2010 I lost the use of my left hand for typing, which lasted through the following summer. Then I realized I could just write by hand in notebooks (I am right-handed), and we bought an iPad for writing when my hand is weak, because less strength is required to type at the speed of thought. And I must go that quickly because with my cognitive difficulties I may forget where things are going. I am considering trying dictation software.

Aside from the physical limitations, I think writing differs for me depending upon whether I am writing poetry or prose. With poetry I am always entering that timeless flow, where the hours spent on one poem feel like a very short time, and I am surprised to notice the sun going down.That can occur with prose, too, but it takes much longer, so there are naturally interruptions.

Writing allows me to adopt any kind of voice and step into a refraction, or set of refractions, of my self, and create something separate, outside the body but of the body, that answers questions I have about experience, or about physicality. Writing leads me into uncharted territory, where I may learn something about myself I had not previously understood.

Q: When my husband and I visited an old friend of his who lives in Chico, this fellow took us to see some of his friends. The wives of two out of the three were in wheelchairs, one due to MS. I found the visits a little destabilizing. I joked later about the "wheelchair wives of Chico," joking because it was too easy to fear becoming one of them. Do you have any thoughts about cartoonists who derive humor from their own disabilities? (I'm thinking of John Callahan, now deceased, but there are others.)

I wasn’t previously aware of Callahan, no. And I do think there is a lot of humor to disability, or any medical situation. There has to be. But more importantly, I think, is the way that we are groomed to fear and feel destabilized by disability or illness as the worst-case scenario, as devastating, as not living. People imagine disability as being bound to something, as I mentioned earlier, and also as incredibly traumatic. I wonder how much humor, at the expense of people with disabilities, by people without them, is simply a response to this deep seated and reinforced fear. Sometimes it’s well-done, and sometimes not so much. Nancy Mairs, a marvelous writer with MS, laughs at herself in her writing but also shows pride. Sometimes people with chronic illness or disability will attempt to comfort non-disabled people by making fun of themselves, too, and I am guilty as charged, but it also makes me feel a little dirty.

Q: Has the Internet influenced your life with MS?

I have used the internet as a research tool. For instance, when my eye pain first began, I found that pain with eye movement was indeed a symptom of optic neuritis, and I should get it checked out. Before going on Tysabri, after having difficulty with every other medication available, I looked long and hard at what Tysabri users were reporting as side effects, because of my track record with the interferons and Copaxone.

But I would also caution the newly diagnosed against message boards and suggest instead that they first visit more reputable sites like the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. There is a lot of misinformation out there, and often newly-diagnosed people are desperate for any kind of treatment, some of which can be harmful or inspire false hope.

Q: You've said that you don't believe that your MS was any kind of gift to be thankful for. However, if you had to choose never being allowed to write another word in order to be cured, would you do it?

I imagine your question is in response to something paraphrased by Alice Walton on her profile of me: that I am not “universally thankful.” Her next paragraph speaks of what I am grateful for with MS and the perspective it gave me.

It would be naïve to claim that MS is all sunshine, rainbows, glitter and unicorns, unless the unicorns are particularly ornery and randomly poke their MS-addled companions with their horns, bite us, and kick us. There is of course limitation, difficulty, pain, and an awareness of one’s faculties diminishing. However, I have actually written quite a lot about how MS is the gift that brought me to poetry, especially in my essay “Reshaping the Outline” in the anthology that came out last year, Beauty Is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability.

I do not see MS as something separate from me but intricately woven into every pattern of my life, every thought, every choice. Even what I teach in the Honors College at UH—Literature and Medicine, Film and Medicine, Readings in Medicine and Society—is shaped by my observations from a life as a professional patient. I don’t know how my life would be without it, and I wonder if there were indeed a cure, would it just arrest the progression, or would it bring me back to “normal”? What state would that be?

Given the sort of binary set-up in your hypothetical situation—MS remaining with the ability to write versus a cure with no possibility of writing again, I would easily choose MS. How would I ever be brought back to normal, since MS has shaped what normal is? It’s not the greatest, but it’s my life and I wouldn’t trade it in.

• Some of Laurie Clements Lambeth's poetry and essays can be read at her site.

• Read her poem "Symptoms" in Disability Studies Quarterly (it's in Veil and Burn also).

• Read this enlightening interview in which we learn that Lambeth has a lovely sense of humor: "If metaphor can be felt, physically felt, and even more so when tied to cadence, then poetry must have the power to cultivate empathy, which could indeed change the world. This is a theory still in development (language is slippery and hard to place into vials), and we are currently conducting double-blind studies in our imaginary poetry laboratories."

• Hear Lambeth read (at about 48 minutes in).

• Lambeth has new poems appearing in Zone 3, including “Upon Reading the Radiologist’s Report.”

• Check out Lambeth's candid and informative blog for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Copyright (2012) by Susan K. Perry