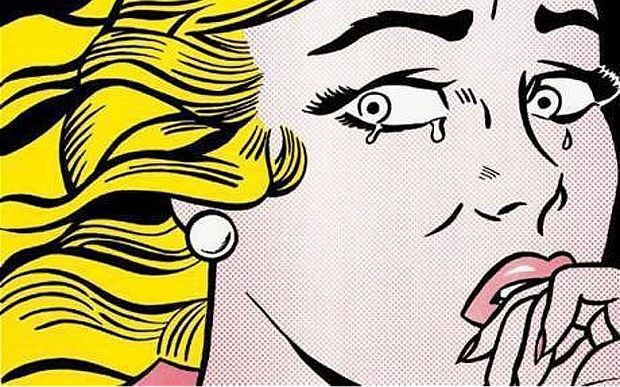

Anger

The Biggest Myths About Emotions & How to Weaken Their Grip

Where do emotions live? The answer may surprise you.

Posted September 12, 2013

With all the chatter about emotions and the brain, you might think that neuroscience is the only exciting frontier in the study of human emotionality. You’d be wrong, though.

Just as busy are the social psychologists, the relational therapists, and the postmodern and the CHAT (cultural-historical activity theory) theorists. As one of them, I can share some of the latest thinking about our emotional lives. A lot of it goes against the dominant view and while I won’t shatter the major myths about emotion that run rampant, I might at least weaken them a bit.

Emotions are an activity, a form of life. If they’re “located” anywhere, they’re in the world, not in our heads.

Emotions are culturally and socially produced and created. Their meaning is in how they’re being responded to by others and by ourselves—both in the moment and in the ongoing cultural and social history of emotions.

The expression “form of life” comes from the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was countering the “obsession” philosophers and scientists have for consistency, for having things fit together, correspond to one another, and be causally connected—leading them down the dark hole of reductionism from which there was no escape. Here’s an excerpt from Wittgenstein’s writings I especially like. It’s not about emotions per se, but it makes his point rather well and shows his unique style of writing in numbered paragraphs. (I think every therapist should try reading Wittgenstein.)

I saw this man years ago: now I have seen him again, I recognize him, I remember his name. And why does there have to be a cause of this remembering in my nervous system? Why must something or other, whatever it may be, be stored-up there in any form? Why must a trace have been left behind? Why should there not be a psychological regularity to which no physiological regularity corresponds? If this upsets our concepts of causality then it is high time they were upset. (from Wittgenstein’s Zelig, paragraph 905)

There are neurological and cognitive processes going on whenever we do anything, so of course they’re going on whenever we recognize, remember and are emotional. But it doesn’t follow that these processes are causally connected to or correspond to what we’re recognizing, remembering or being emotional about, or to human activity of recognizing, remembering or being emotional.

Emotions aren’t things we have or possess. They’re things we do. Some of us cultural and postmodern oriented psychologists make emotions actions. We see and study how people “perform emotions” and “create emotional scenarios.” We prefer these active, theatrical terms to the usual static noun that abandons emotionality’s socialness and relationality and, with it, its meaning.

We can—and do—create new emotional forms of life. We don’t have a fixed or finite number of emotions.

Many experts believe that emotions they should and can be defined and classified. They come up with the “basic” emotions (usually 6 or 8, including fear, happiness, anger, joy, etc.) and then create lists of dozens of combinations of these basic ones. They hold to an “essentialist” view that emotions are, well, emotions—no matter when and where you live or who you are. But for those of us who disagree, that makes no sense. If everything about our lives is different today from a hundred years ago, our emotional lives are different. If my life is nothing life a twelve year-old Syrian boy’s life, how can our anger be the same? What goes on in our brains might be the same but in no way does that mean our anger is the same.

Whatever you think of emoticons, the hundreds available—with more appearing every week—suggests that people (at least those who use social media) aren’t limiting themselves to the “6 (or 8) human emotions,” but are playing with ways to share their rich emotional forms of life in entirely new ways. Who knows, maybe this kind of play is enriching their emotional lives.