Ethics and Morality

Milgram Revisited: Craig Zobel's "Compliance"

Sometimes it's important to watch uncomfortable films

Posted August 16, 2012

By Jonah Comstock

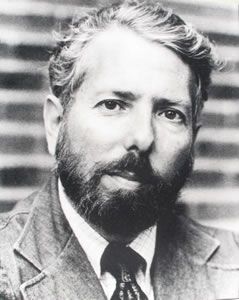

Stanley Milgram

In 1961 at Yale, Stanley Milgram completed a series of experiments that would become among the most famous in the history of psychology. Studying obedience to authority, Milgram staged scenes where subjects were instructed to deliver what they believed to be painful electric shocks to strangers. Milgram found that 65 percent of subjects were willing to let obedience to the lab-coat-wearing authority trump their innate morality—though some begged and pleaded to be allowed to stop, they never refused to comply and they all administered the highest shock the machine gave out—450 volts.

I've known about the Milgram experiments for many years, but, as chilling as they are, I've never lost any sleep over them. This was just an experiment in a lab, I told myself, not the real world. In real life, surely fewer people would succumb to the pressure. Psychology Today recently co-hosted a screening of Craig Zobel's acclaimed film Compliance. The film is an examination of a real-world Milgram experiment, conducted not in the name of science but as part of a sick criminal act.

In the film, a man calls a fast food restaurant in a rural town and, pretending to be a police officer, tells Sandra, the manager, that young, female employee Becky has stolen money from a customer. In an escalating series of lies and instructions, Sandra is convinced first to take Becky's clothes, and then to call her fiance, Van, and leave him alone in the room with Becky and the phone. The caller convinces Van to rape and assault Becky before a daytime employee finally puts a stop to the madness. The filmmaking is close and raw, the performances jarring and real.

The film is incredibly disturbing to watch, and at the screening it elicited a certain amount of incredulity— not only “nobody would do that” but also “nobody would believe that.” But at the Q&A it became clear that a certain amount of that resistance is wishful thinking—it's much preferable to believe the film was badly made than to believe the truth. This could happen. This did happen. The events of the film are directly based on a 2004 crime at a McDonalds in Montana. Prior to that incident, which eventually ended in an arrest (although, appallingly, not a conviction), over 70 similar phone calls were reported that led to some kind of humiliation and/or assault of an employee or customer.

Ann Dowd as Sandra

After the film, Psychology Today Editor-at-large Hara Estroff Marano moderated a panel with Zobel, actress Ann Dowd, and two psychologists and Psychology Today bloggers: Stanton Peele and Nando Pelusi. The discussion was short, but it was heated and emotional. Dr. Peele asked the audience to raise their hands if they thought they would have succumbed—and nobody did. But Marano pointed out that prior to the Milgram experiment, 100 psychology students and faculty at Yale said the same thing: they predicted hardly anyone would go along with it. The only characters in the film who really stood up were the screw-ups, the ones who never had much respect for authority at all. And even they only went as far as refusing to participate.

Dr. Peele pressed even harder, asking why, if we all found the movie so disturbing, we didn't just get up out of our seats—whether maybe some sense of what we were supposed to do overrode what we individually might have wanted to do, just as a sense of “supposed to” overrode the morality of the film's characters. It's a weak parallel in some ways—watching a movie doesn't hurt another person —but it captured the brilliance of the film: it made us uncomfortable because it put us into the character's situation.

It's not a fun movie to watch, but it does something that art should—it makes us think about a part of our history and a part of ourselves that we would much rather avoid. And forcing ourselves to think about this disturbing aspect of human nature could be very, very important.

Dreama Walker as Becky

Milgram took a lot of heat for his experiment on the grounds that the emotional trauma he put his subjects through was unethical. But his subjects themselves responded to a survey, and over 90 percent said they were glad to have participated. One subject wrote Milgram to tell him that experience had given him the strength to be a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War—that is, to stand up for his own morals in the face of the authority of the whole United States of America.

That's what we can hope to gain by making ourselves sit through this uncomfortable film; by putting ourselves in the shoes of Sandra and Becky. We each hope we're in the minority that would stand up for what's right, and we each hope we'll never have to find out if we are. But perhaps by confronting the dark conformity of human nature through art, we can be more prepared if we ever meet it in life.

Jonah Comstock is a summer intern at Psychology Today. A version of this post appears today at The Analytical Couch Potato.