Trauma

Drawing Alone: Making Art in Solitary Confinement

How drawing helped a female inmate survive solitary confinement

Posted June 10, 2014

Since I began this blog last year, one of my Graduate Assistants, Jaimie Burkewitz, has been invaluable in helping me develop its focus and provided much needed feedback for each post through her fresh pair of eyes. She will be graduating this August from Florida State University with her MS in Art Therapy. Because of her interest in art therapy and forensics, her third and final practicum internship placement was a privately owned, state contracted, women’s prison. She proved to be a compassionate and effective clinician, and had many notable and valuable experiences providing art therapy sessions for the women. One involved providing services to two separate inmates who had been previously placed in solitary confinement. One had an opportunity to draw while in there—one did not.

Ms. Burkewitz was asked to write about this experience as a guest blogger for this site.

Drawing Alone: Making Art in Solitary Confinement

By Jaimie Burkewitz

"Monsters, this is what they created here, monsters. And then they drop you in society and tell you 'go ahead be a good boy.' You can't conduct yourself like a human being, when they treat you like an animal." -Inmate in solitary in a Maine state prison (PBS Video, The sounds of solitary. Aired 4/22/14)

* * *

Solitary confinement (aka segregation, administration segregation [Ad Seg] or “the hole”) began in the early 1900's as a means of rehabilitation. However, it has shown to have had the opposite effect--leaving inmates devoid of human contact and stimulation, and causing many to become "mentally disturbed." The mission statement of most correctional institutions underscores an intention to rehabilitate their wards into contributing members of society upon their release. Yet, it seems antithetical to strip away everything that makes someone human for extended periods of time through such confinement.

This post introduces a distinctive perspective on confinement by comparing the different experiences of two female inmates. One was in a maximum-security institution; one was in a low security correctional facility. Upon return to general population, one tried to commit suicide, the other claimed it "worked for her." What was different? One contributing factor may have been that one was given a 3-inch long pen and a few sheets of paper.

* * *

Six months ago, for my third and final art therapy practicum training I expected to be placed in ‘a prison’. Instead, I found myself a privately owned correctional facility housing female inmates with an emphasis on rehabilitation.

The site was within the prison’s department of mental health; I received supervision from the institution's head psychologist and the art therapy faculty from the FSU art therapy program. I saw many women, in groups and in individual sessions.

About mid-way through the semester, something interesting happened that compelled me to delve into the world of solitary confinement.

My supervisor referred a client to me who she felt could benefit from individual attention with an art therapist. Normally I would have hesitated working with someone new with only a month remaining in my practicum. However, this particular woman had an extremely complex history of trauma, an affinity for and desire to create art, and had recently transferred from a maximum-security institution where she was looking at a life sentence. I agreed to see her, believing that an art therapist could offerthe inmate unique strategies to cope with such a huge transition. We began meeting twice weekly.

Her once dismal sentence reduced, she spent many episodes over the past 13 years in solitary confinement for various aggressive acts before being transferred to my correctional facility. Her main concern was the anxiety she felt in being exposed to such an overwhelming influx of stimuli - including 1,500 other women living in open dormitory style buildings. During our sessions, more deeply rooted issues rose to the surface and became the primary focus of our discussions and her art. Detailed visions and descriptions of her experiences growing up in an extremely abusive family, how she killed her grandmother, what it was like to spend so much time in solitary confinement and her effort to end her life by hanging were relayed most effectively through her newfound desire to paint (she had only used pencils before).

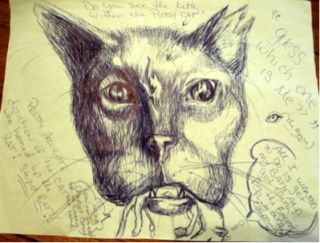

figure 1: Painting symbolic of solitary confinement created years later

While she was encouraged to paint intuitively while talking about her experience, she painted this image [see figure 1] literally carved out of layers of thick paint laid down in broad strokes with the paintbrush’s handle. This was done in a small, cinderblock room not unlike a prison cell with relaxing music playing. She claimed that it was only in this environment that she felt the most comfortable expressing herself. It was as if she and I entered her manifestation of life in confinement and then emerged suddenly as she claimed to have done. Although I believe she purposefully added prison bars as the final touch, it was fascinating that neither of us recognized the curving line in the center as a figure until we stepped away.

While painting, the client spoke about what she felt while in confinement. She said after about 60 days she began hearing and seeing things. She began losing her ability to communicate and experienced "disconnected feeling and words." She felt her "sanity slipping" and "could no longer differentiate between reality and illusion." After about 90 days she claimed to completely lose hope, feeling she had "nothing to live for," that no one could or would understand that she was alone. This is when she tried to hang herself in her cell.

When I asked her why she thought painting about what it was like to be in solitary seemed to make her feel better even though it was some time ago, she responded, "it releases a lot of inner conflict when you can't verbally communicate." This image clearly seems to reflect this conflict and seclusion.

* * *

Coincidentally, at the same time, another client who had been in one of my groups was transferred from her dorm and sent into confinement for "disrespecting staff." After she was released she and I began meeting.

I found her experience to be quite different.

She said she kept telling herself, "This is how it could be,” making her appreciate the facility more. She explained:"I was getting too complacent.... Some of us will see that we got caught and think, 'how can I not get caught next time?'...others think, 'how can I fix the real problem--what made me do this in the first place?' and find the tools that can help them."

For some reason, she was allowed to have a small prison pen and a few sheets of paper. According to her, these became her tools for survival.

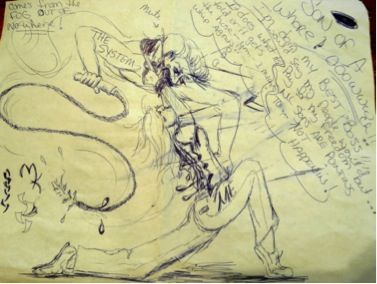

figure 2: Drawn in confinement- how she used to be a correctional officer and now she is the prisoner (the rat).

When commenting on her ability to draw while in confinement the client said, "it comes to a point where you have to make a decision; are you going to be controlled or are you going to take control? I survived by focusing on the here and now instead of the long-term things I couldn't control. I'm glad I had paper and a pen-- I was able to lash out...it gave me release, and it gave me a sense of control."

figure 3: drawn in confinement- "When I was really angry"

She even kept the pens after as a reminder because as she says, "others look at me like I'm crazy or 'better' because I want to better myself...This is how I keep my sanity." She completed the next three figures while in solitary. The captions for each image indicate what she said about each piece. Expressive, and in some ways aggressive, they provided her a means to immediately address the seclusion and lack of stimulation, allowing her to find a much needed outlet that would ease her transition into general population upon release.

figure 4: drawn in confinement: "This I did when I wasn't mad anymore"

* * *

Two women sent to confinement, yet two entirely different outcomes. Which would you rather have released into society- a woman who lost her sense of and hope for humanity, or a woman who through self-expression was able to gain perspective and release her anger in a healthier more meaningful way?