Cognition

Gandhian Economics, Universal Well-Being, and Human Needs

For Gandhi's birthday: Some thoughts on the current relevance of his economics

Posted October 2, 2013

As this entry is being posted, it's Gandhi's birthday. Given how much I have been influenced, even transformed, by learning from Gandhi about nonviolence, I wanted to write something to honor his legacy. Because I've recently started a mini-series on money, I decided to focus on a lesser known aspect of Gandhi's work: his views about economics.

At first sight, many of Gandhi's basic economic thoughts seem entirely irrelevant to our very different time, culture, and context from the one in which he operated and wrote. For example, the idea of village cottage industry, which might have been feasible in early 20th century India, is very hard to imagine now as a primary way forward for industrialized economies. Delving into it a bit deeper, I see a number of convergences between his ideas and the direction that many are advocating today, such as simplicity, localism, and decentralization. Rather than an exhaustive introduction to Gandhian economics, which can be found through a search on the web, I chose, instead, to look more deeply at two core principles that resonate deeply with me and the path I am on with regards to thinking about money and the economy. This week, I am looking at the question of what constitutes universal well-being and how we approach the conundrum of attending to human needs. Next week I plan to look at Gandhi's notion of trusteeship and connect it with current unfolding thoughts about the Commons.

Needs and Wants

The fundamental basis of Gandhian economics is a commitment to universal well-being. Like so many who are interested in universal well-being, Gandhi was led, inexorably, to looking at the difficult question of need satisfaction, since physical finitude makes it clearly impossible for everyone to have everything they want all the time. Like many others, he attempted to address this challenge by supporting a shift from the multiplication of wants to the fulfillment of needs.

If only it were so simple. As Kate Soper, an academic researcher in the field of human needs observes in On Human Needs: "we hear and read repeatedly of 'basic' 'needs, 'true' needs, 'false' needs, 'spiritual' needs, 'material' needs, unconscious needs, of 'needs' as opposed to 'wants' or 'desires', of 'needs' as opposed to 'luxuries', of 'actual' as opposed to 'potential' needs." This is a category fraught with difficulties on a variety of levels. It includes questions of what's true of reality, how we know and identify it, and what we do about it. For those who have studied philosophy, we have epistemological, ontological, and moral dimensions to the complexity. No wonder we haven't figured this one out completely. This means we are challenged to identify what a need is and distinguish it from other forms of wanting, wishing, or desiring. This difficulty is not idle or purely theoretical, because the deeper question of whether or not needs can be met is completely tied up with what we mean by a need, and both are intertwined with whether or not we decide, collectively, to put efforts into trying to meet them, along with figuring out the even more perplexing question of who decides what counts as a need when it comes time for resource allocation.

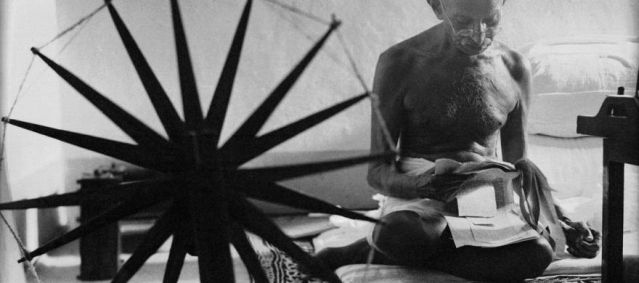

From GandhianEconomics.com

From this perspective, I can see so clearly the appeal of modern capitalism. Rather than attempting to address the question any which way, the lure of capitalism is the promise of a certain kind of freedom: you will be accountable to no one for as long as you can amass enough money to buy everything you want, regardless of whether you need it or not. The translation of needs into market demand appears implicitly to preserve human dignity: no one can decide for anyone what their needs are. Only an impersonal and optimal force will determine which needs will actually get met. The actual question of human needs gets swept under the rug.

The other modern challenge to the possibility of need satisfaction is the Freudian theory of human nature, in which everything we want is reduced to two insatiable and asocial drives. If our inner drives are insatiable, there is no point in attempting to satisfy our needs, because the project is impossible.

Although Gandhi may have not been aware of Freud, he was very aware of the abundance that mass production creates (abundance I believe to be imaginary, because of invisible costs - to nature, to other people, to social ties, to the future). His project, as I understand it, was more on the moral and spiritual plane than the actual economic and practical plane. He issues an invitation, to all of us, to become ever more aware of the proliferation of options that don't add to real choice, and to choose to go against that current by coming closer and closer to our essential needs.

Reaching clarity about what our needs really are and how they differ from the almost infinite array of strategies we have for attempting to meet them is one of the core practices of the work I've been studying and teaching for years: Nonviolent Communication. This practice delineates clear guidelines for deciding (see The What and the Why in Human Needs), and yet leaves the final decision for each person to figure out for themselves. This process sidesteps the oppressive path of someone from the outside deciding for us what constitutes a need, while at the same time achieving the beneficial results that come from moving closer to the core as proposed by Gandhi.

Unfortunately, the lure of capitalism has only grown since Gandhi's day, making it that much more difficult to tease apart needs in the arena of material satisfaction, especially when it comes to money itself, the universal translator of needs in our world. We all have many physical, relational, and emotional needs bound up with money and material possessions. I know of no effective way to be able to get to true clarity amidst the emotionally overwhelming bombardment of our senses and minds by injunctions to consume. That said, the trend of embracing some degree of voluntary simplicity appears to be growing in the last few decades, as more and more people recognize the costs of a high-consumption lifestyle.

All of this leaves unaddressed, still, the question of how we make the shift from wants to needs. One core insight that I find profoundly liberating and core to the possibility of need satisfaction is the realization that although most of what we want, moment by moment, is not in itself a need, it is also not separate from what we need, and there is always some underlying need which informs and motivates every action we take and every wish we harbor. In contrast to Freud and other human nature pessimists, I have embraced the faith that there is no inherent insatiability to our core human needs. Put differently, I believe that we are capable of satisfaction, and that we can experience it much more often, reliably, and deeply, if we create, collectively and globally, conditions that support human flourishing. Although my language is different from Gandhi's, I believe that this framework, and the practice that emerges from it, are consistent with Gandhi's vision of an economy that is geared towards the general well being of all humanity.

Click here to read the Questions about this post, and to join us to discuss them on a conference call next Tuesday, October 8, 5:30-7 pm Pacific time. This is a way that you can connect with me and others who read this blog.We are asking for $30 to join the call, on a gift economy basis: so pay more or less (or nothing) as you are able and willing.