The general meaning of relapse is a deterioration in health status after an improvement. In the realm of addiction, relapse has a more specific meaning—a return to substance use after a period of nonuse. Whether it lasts a week, a month, or years, relapse is common enough in addiction recovery that it is considered a natural part of the difficult process of change. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of individuals relapse within their first year of treatment, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Relapse in addiction is of particular concern because it poses the risk of overdose if someone uses as much of the substance as they did before quitting.

Contents

Research has found that getting help in the form of supportive therapy from qualified professionals, and social support from peers, can prevent or minimize relapse. In particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help people overcome the fears and negative thinking that can trigger relapse.

Experts in the recovery process believe that relapse is a process and that identifying its stages can help people take preventative action.

- Emotional Relapse. At this stage, a person might not even think about using substances, but their lack of attention to self-care, their isolation, or their inconsistent attendance at therapy sessions or group meetings sets them up for relapse. This is when an individual needs self-care, sleep, and healthy eating.

- Mental Relapse. This stage is characterized by a tug of war between past habits and the desire to change. Romanticizing past drug use, hanging out with old friends, lying, and thoughts about relapseare danger signs. Coping skills can keep thoughts from escalating into substance use.

- Physical Relapse. Once a person begins drinking or taking drugs, it’s hard to stop the process.

Read More

Relapse is not a sign of failed recovery. It’s an acknowledgement that recovery takes lots of learning, especially about oneself. Recovery from addiction requires significant changes in lifestyle and behavior, ranging from changing friend circles to developing new coping mechanisms. It involves discovering emotional vulnerabilities and addressing them. By definition, those who want to leave drug addiction behind must navigate new and unfamiliar paths and, often, burnish work and other life skills. Recovery also requires discovery or rediscovery and development of interests that have the power to drive pursuit and deliver rewards, not only spurring the addicted brain to rewire itself but giving life real meaning—the ultimate goal of every person.

The risk of relapse is greatest in the first 90 days of recovery, a period when, as a result of adjustments the body is making, sensitivity to stress is particularly acute while sensitivity to reward is low. The risk decreases after the first 90 days. It is important to know that relapse does not represent a moral weakness. It reflects the difficulty of resisting a return to substance use in response to what may be intense cravings but before new coping strategies have been learned and new routines have been established. For that reason, some experts prefer not to use the term “relapse” but to use more morally neutral terms such as “resumed” use or a “recurrence” of symptoms.

There is an important distinction to be made between a lapse, or slipup, and a relapse. The distinction is critical to make because it influences how people handle their behavior. A relapse is a sustained return to heavy and frequent substance use that existed prior to treatment or the commitment to change. A slipup is a short-lived lapse, often accidental, typically reflecting inadequacy of coping strategies in a high-risk situation.

No matter how much abstinence is the desired goal, viewing any substance use at all as a relapse can actually increase the likelihood of future substance use. It can engage what has been termed the Abstinence Violation Effect. It encourages people to see themselves as failures, attributing the cause of the lapse to enduring and uncontrollable internal factors, and feeling guilt and shame. Alternatively, seeing a binge or a slipup as a lapse encourages a person to minimize the size of the lapse, to quickly return to the recovery path, to direct attention to elements that can be controlled, which often means taking time to learn more about personal triggers, beefing up coping strategies, and bolstering a support network.

Just as becoming addicted is a process that involves learning mechanisms in the brain, so is addiction recovery a learning process, and like most learning and growth, it does not occur overnight or in a strictly linear manner. Relapse frequently occurs in response to a trigger. A person on the road to recovery encounters a person or a place associated with addiction or some other reminder of the addictive life and the extreme highs it brought (however destructive they became), and that sets off a longing for the substance.

In the absence of an emergency plan for just such situations, or a new life with routines to jump into, or a strong social network to call upon, or enhanced coping skills, use looms as attractive. Alternatively, a person might encounter some life difficulties that make memories of drug use particularly alluring.

The majority of people who decide to end addiction have at least one lapse or relapse during the recovery process. Studies show that those who detour back to substance use are responding to drug-related cues in their surroundings—perhaps seeing a hypodermic needle or a whiskey bottle or a person or a place where they once obtained or used drugs. Such triggers are especially potent in the first 90 days of recovery, when most relapse occurs, before the brain has had time to relearn to respond to other rewards and rewire itself to do so.

This is especially the case with relapse among addicted youth. They are particularly prone to relapse because they spent their formative years engaged with substances rather than developing a strong social support network, learning basic life skills, or gaining academic achievement—all positive predictors of success. Learning what one’s triggers are and acquiring an array of techniques for dealing with them should be essential components of any recovery program.

Relapse is most likely in the first 90 days after embarking on recovery, but in general it typically happens within the first year. Recovery is a developmental process and relapse is a risk before a person has acquired a suite of strategies for coping not just with cravings but life stresses and established new and rewarding daily routines.

Some evidence suggests that the risk for relapse is heightened just as people are leaving the full-time support of an inpatient treatment program—before they’ve had a chance to practice newly acquired skills and insights, set up their own social support system, or gained insight into their emotional vulnerabilities. They may not recognize that stopping use of a substance is only the first step in recovery—what must come after that is building or rebuilding a life, one that is not focused around use. They may falsely believe that their recovery is complete, or that cravings are a sign of failure, when in fact it takes time to rebuild a life and time for the brain to rewire itself and learn to respond to everyday pleasures. In general, the longer a person has not used a substance, the lower their desire to use.

Recovery is a process of growth and (re)establishing a sustainable life. Experts in addiction recovery believe that relapse is a process that occurs somewhat gradually; it can begin weeks or months before picking up a drink or a drug. Moreover, it occurs in identifiable stages, and identifying the stages can help people take action to prevent full-on relapse.

Emotional Relapse. At this stage, a person might not even think about using substances, but there is a lack of attention to self-care, the person is isolating from others, and they may be attending therapy sessions or group meetings only intermittently. Attention to sleep and healthy eating is minimal, as is attention to emotions and including fun in one’s life. Self-care helps minimize stress—important because the experience of stress often encourages those in recovery to glamorize past substance use and think about it longingly.

Mental Relapse. The longer someone neglects self-care, the more that inner tension builds to the point of discomfort and discontent. Cognitive resistance weakens and a source of escape takes on appeal. This stage is characterized by a tug of war between past habits and the desire to change. Thinking about and romanticizing past drug use, hanging out with old friends, lying, and thoughts about relapse are danger signs. Individuals may be bargaining with themselves about when to use, imagining that they can do so in a controlled way. Coping skills can keep thoughts from escalating into substance use.

Physical Relapse. Once a person begins drinking or taking drugs, it’s hard to stop the process. Good treatment programs recognize the relapse process and teach people workable exit strategies from such experiences.

Most people relapse in response to some internal or external trigger. Triggers can be negative—experiencing stress or uncomfortable feelings from which a person wants to escape—or positive, such as seeing a place associated with past addictive behavior, which can set off a chain of associations culminating in the urge to use. Common triggers include:

• The discomfort of withdrawal symptoms.

• Unpleasant feelings including hunger, anger, loneliness, and fatigue.

• Feeling isolated. Being alone with one’s thoughts for too long can lead to relapse.

• Seeing old friends who still use drugs.

• Finding oneself in places associated with past drug use.

• Over-confidence that everything is under control.

• Breakups.

Setbacks are an opportunity to learn—to learn more about triggers one is sensitive to, to understand what makes a situation high-risk for an individual, to learn when to ask for help, to gain more coping skills, Relapse is an indicator that more intensive support is needed, and it is especially critical in the first few months of recovery. At that time, there is typically a greater sensitivity to stress and lowered sensitivity to reward.

A lapse or relapse should be regarded as a signal to:

• Manage triggers.

• Build a support network of friends and family to call on when struggling and who are invested in recovery.

• Avoid situations where people are likely to use drugs or alcohol.

• Learn ways of managing stress.

• Address negative thinking patterns: “I’m a failure,” “I’ve let everyone down,” “I can’t handle life without using,” “Recovery takes too much work,” “I can’t resist the cravings,” all of which tend to reflect black-and-white catastrophizing and set the stage for relapse.

People can relapse when things are going well if they become overconfident in their ability to manage every kind of situation that can trigger even a momentary desire to use. Or they may be caught by surprise in a situation where others around them are using and not have immediate recourse to recovery support. Or they may believe that they can partake in a controlled way or somehow avoid the negative consequences. Sometimes people relapse because, in their eagerness to leave addiction behind, they cease engaging in measures that contribute to recovery. They may focus less on self-care.

There is considerable controversy in the field of addiction whether people are in constant danger of relapse. Many people subscribe to a disease model of addiction—they see addiction strictly as a medical condition, a chronic brain disease that endures forever. According to such a view, those who have been addicted exist in a fragile state of recovery for the rest of their lives, in constant danger of relapsing. Constant vigilance is required.

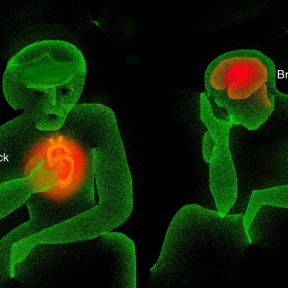

That view contrasts with the evidence that addiction itself changes the brain—and stopping use changes it back. Use of a substance delivers such an intense and pleasurable “high that it motivates people to repeat the behavior, and the repeated use rewires the brain circuitry in ways that make it difficult to stop. Evidence shows that eventually, in the months after stopping substance use, the brain rewires itself so that craving diminishes and the ability to control behavior increases. The brain is remarkably plastic—it shapes and reshapes itself, adapts itself in response to experience and environment.

The belief that addiction is a disease can make people feel hopeless about changing behavior and powerless to do so. It keeps people focused on the problem more than the solution. Seeing addiction instead as a deeply ingrained and self-perpetuating habit that was learned and can be unlearned doesn’t mean it is easy to recover from addiction—but that it is possible, and people do it every day. It is in accord with the evidence that the longer a person goes without using, the weaker the desire to use becomes.

Relapse is emotionally painful for those in recovery and their families. Nevertheless, the first and most important thing to know is that all hope is not lost. Relapse triggers a sense of failure, shame, and a slew of other negative feelings. It’s fine to acknowledge them, but not to dwell on them, because they could hinder the most important action to take immediately—seeking help. Taking quick action can ensure that relapse is a part of recovery, not a detour from it.

• Ask for help. Many people seeking to recover from addiction are eager to prove they have control of their life and set off on their own. Studies show that social support boosts the chances of success. Help can come in an array of forms—asking for more support from family members and friends, from peers or from others who are further along in the recovery process. It might mean entering, or returning to, a treatment program; starting, or upping the intensity of, individual or group therapy; and/or joining a peer support group.

Some people arrange a tight network of friends to call on in an emergency, such as when they are experiencing cravings. Since cravings do not last forever, engaging in conversation about the feelings as they occur with someone who understands their nature can help a person ride out the craving. Others take advantage of the many types of peer support groups that provide, in addition to useful information, the wisdom and coping strategies of others who have faced the same hurdles; it is the ethos of such groups that members support their peers through crises without judgment.

Mutual support groups are usually structured so that each member has at least one experienced person to call on in an emergency, someone who has also undergone a relapse and knows exactly how to help. What’s more, attending or resuming group meetings immediately after a lapse or relapse and discussing the circumstances can yield good advice on how to continue recovery without succumbing to the counterproductive feelings of shame and self-pity. It can be a make-or-break source of hope.

• Reflect on the triggers. Reflect on what triggered the relapse—the emotional, physical, situational, or relational experiences that immediately preceded the lapse. Inventory not only the feelings you had just before it occurred but examine the environment you were in when you decided to use again. Sometimes nothing was going on—boredom can be a significant trigger of relapse. Such reflection helps you understand your vulnerabilities—different for every person. Armed with such knowledge, you can develop a contingency plan to help you avoid or cope with such situations in the future.

• Boost self-care. Engaging in self-care may sound like an indulgence, but it is crucial to recovery. For one, it bolsters self-respect, which usually comes under siege after a relapse but helps motivate and sustain recovery and the belief that one is worthy of good things. Too, maintaining healthy practices, especially getting abundant sleep, fortifies the ability to ride out cravings and summon coping skills in crisis situations, when they are needed most.

• Continue changing your life. Not using substances is only one part of recovery. Creating a rewarding life that is built around personally meaningful goals and activities, and not around substance use, is essential. Recovery is an opportunity for creating a life that is more fulfilling than what came before. Attention should focus on renewing old interests or developing new interests, changing negative thinking patterns, and developing new routines and friendship groups that were not linked to substance use.

• Develop a relapse prevention plan. Recovery benefits from a detailed relapse prevention plan kept in a handy place—next to your phone charger, taped to the refrigerator door or the inside of a medicine cabinet—for immediate access when cravings hit. Such a plan helps minimize the likelihood of lapses in the future. A good relapse prevention plan specifies a person’s triggers for drug use, lists some coping skills to summon up and distractions to engage in, and lists people to call on for immediate support, along with their contact information.

• Forgive yourself. Changing bad habits of any kind takes time, and thinking about success and failure as all-or-nothing is counterproductive. Setbacks are a normal part of progress in any aspect of life. In the case of addiction, brains have been changed by behavior, and changing them back is not quick. Research shows that those who forgive themselves for backsliding into old behavior perform better in the future. Getting back on track quickly after a lapse is the real measure of success.

How individuals deal with setbacks plays a major role in recovery—and influences the very prospects for full recovery. Many who embark on addiction recovery see it in black-and-white, all-or-nothing terms. They see setbacks as failures because the accompanying disappointment sets off cascades of negative thinking and feeling, on top of the guilt and shame that most already feel about having succumbed to addiction.

Setbacks can set in motion a vicious cycle, in which individuals see setbacks as confirming their negative view of themselves and see themselves as incapable and/or unworthy of living a substance-free life. Such a negative mindset can not just usher in a return to using but compound a sense of failure, which makes the journey of recovery appear even more daunting

The healthy alternative to seeing relapse as personal defeat is to regard it as a steppingstone, a marker of progress—a chance to learn more about one’s individual susceptibilities, about the kinds of situations that are problematic, and about the most workable means of support in a crisis.

Regarding setbacks as a normal part of progress enables individuals to broaden their array of coping skills, to engage in planning for problematic situations, and to devise strategies in advance for dealing with predictable difficulties. Among the most important coping skills needed are strategies of distraction that can be quickly engaged when cravings occur. Mindfulness training, for example, can modify the neural mechanisms of craving and open pathways for executive control over them.

Also critical is building a support network that understands the importance of responsiveness. Not least is developing adaptive ways for dealing with negative feelings and uncertainty. Those ways are essential skills for everyone, whether recovering from addiction or not—it’s just that the stakes are usually more immediate for those in recovery. Many experts believe that people turn to substance use—then get trapped in addiction—in an attempt to escape from uncomfortable feelings.

The causes of substance dependence are rarely obvious to users themselves. Addiction recovery is most of all a process of learning about oneself. A better understanding of one’s motives, one’s vulnerabilities, and one’s strengths helps to overcome addiction.

Craving is an overwhelming desire to seek a substance, and cravings focus all one’s attention on that goal, shoving aside all reasoning ability. Perhaps the most important thing to know about cravings is that they do not last forever. It is also necessary to know that they are not a sign of failure; they are inevitable. But their lifespan can be measured in minutes—10 or 15—and that enables people to summon ways to resist them or ride them out. Moreover, their intensity lessens over time.

Cravings can be dealt with in a great variety of ways, and each person needs as array of coping strategies to discover which ones work best and under what circumstances. Distraction is one approach. Many people draw on mindfulness meditation. One strategy is to shift thinking immediately as a craving arises. Another is to carefully plan days so that they are filled with healthy, absorbing activities that give little time for rumination to run wild. Exercise, listening to music, getting sufficient rest—all can have a role in taking the focus off cravings. And all strategies boil down to getting comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Helpful techniques include:

• Accept. Recognize that cravings are inevitable and do not mean that a person is doing something wrong.

• Delay. Tough it out. It will pass.

• Distract. Go for a walk, take a shower, play music, play a video game, call someone in your support network.

• Escape. If you are at a gathering where provocation arises because alcohol or other substances are available, leave. Cravings can intensify in settings where the substance is available and use is possible.

• Go for a walk or run or other exercise. It’s not only works as a distraction but also bolsters the ability to summon the power of judgment and other regulatory functions.

• Engage in mindfulness meditation. Learning techniques of mindfulness allows you to distance yourself from the e craving and examine it rather than automatically accept its command.

Cravings occur because the human brain has remarkable powers of association. They are typically triggered by people, places, paraphernalia, and passing thoughts in some way related to previous drug use. In the absence of triggers, or cues, cravings are headed toward extinction soon after quitting. But sometimes triggers can’t be avoided—you accidentally encounter someone or pass a place where you once used. Moreover, the brain is capable of awakening memories of drug use on its own.

Sleep regulates and restores every function of the human body and mind. The power to resist cravings rests on the ability to summon and interpose judgment between a craving and its intense motivational command to seek the substance. Stress and sleeplessness weaken the prefrontal cortex, the executive control center of the brain. They rob people of the power to resist impulses.

Sleep deprivation undermines recovery in indirect ways as well. It weakens emotional control. It intensifies the effects of stress. It exacerbates depression and anxiety. And it robs people of the energy needed to rebuild their life.

Many factors play a role in a person’s decision to misuse legal or illegal psychoactive substances, and different schools of thinking assign different weight to the role each factor plays. Among the factors known to influence the development of addiction are feelings about oneself, emotional state, the quality of family relationships, social ties, community attributes, employment status, stress reactivity and coping skills, physical or emotional pain, personality traits, educational opportunities, life goals, and progress toward them.

Some models of addiction highlight the causative role of early life trauma and emotional pain from it. Some people contend that addiction is actually a misguided attempt to address emotional pain. However, it’s important to recognize that no one gets through life without emotional pain. And most people who experience trauma do not become addicted.

A great deal of research demonstrates that a pile-up of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as trauma, especially when combined with a chaotic childhood, raises the risk for a number of types of dysfunctional behavior later on, of which addiction is only one. The more ACEs children have, the greater the possibility of poor school performance, unemployment, and high-risk health behaviors including smoking and drug use.

Prolonged stress during childhood dysregulates the normal stress response and can lastingly impair emotion regulation and cognitive development. What is more, it can alter the sensitivity of the stress response system so that it overresponds to low levels of threat, making people feel easily overwhelmed by life’s normal difficulties. Research shows a strong link between ACEs and opioid drug abuse as well as alcoholism.

Helping people understand whether emotional pain or some other unacknowledged problem is the cause of addition is the province of psychotherapy and a primary reason why it is considered so important in recovery. Therapy not only gives people insight into their vulnerabilities but teaches them healthy tools for handling emotional distress.

Whether or not emotional pain causes addition, every person who has ever experienced an addiction, as well as every friend and family member, knows that addiction creates a great deal of emotional pain. Therapy for those in recovery and their family is often essential for healing those wounds.

Typically, those recovering from addiction are filled with feelings of guilt and shame, two powerful negative emotions. Guilt reflects feelings of responsibility or remorse for actions that negatively affect others; shame reflects deeply painful feelings of self-unworthiness, arising from the belief that one is inherently flawed in some way. As a result, those recovering from addiction can be harsh inner critics of themselves and believe they do not deserve to be healthy or happy.

Such feelings sabotage recovery in other ways as well—negative feelings are disquieting and are often what drive people to seek relief or escape in substances to begin with. In addition, feelings of guilt and shame are isolating and discourage people from getting the support that that could be of critical help.

What is more, negative feelings can create a negative mindset that erodes resolve and motivation for change and casts the challenge of recovery as overwhelming, inducing hopelessness. A relapse or even a lapse might be interpreted as proof that a person doesn’t have what it takes to leave addiction behind.

Therapy is extremely helpful; CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) is very specifically designed to uncover and challenge the kinds of negative feelings and beliefs that can undermine recovery. By providing the company of others and flesh-and-blood examples of those who have recovered despite relapsing, support groups also help diminish negative self-feelings, which tend to fester in isolation.

It is possible to overcome shame—by releasing it. Shame diminishes as recovery proceeds. Neuroscientist Adi Jaffe, who himself overcame severe addiction, identifies five steps for doing so:

1. Identify important past events that gave rise to negative beliefs about yourself.

2. Inventory personal strengths as well as weaknesses.

3. Identify features in your life—relationships, work—that can help take the focus off addictive behaviors.

4. Shift perspective to see relapse and other “failures” as opportunities to learn.

5. Choose to get help, even though shame often deters people from doing so.

Experts agree that the best way of maintaining recovery is to engage all the positive recovery practices—seeking the input of others, reflecting on triggers of desire to use, acquiring skills to tolerate discomfort, hewing to a program of self-care, building new interests, finding new sources of meaning in life, polishing a relapse prevention plan—and to avoid overconfidence about one’s ability to withstand high-risk situations. It’s also necessary to schedule regular opportunities for fun.

Equally important is to learn to identify situations that carry high risk of relapse and to develop very specific strategies for dealing with each of them. High-risk situations include both internal experiences—positive memories of using or negative thoughts about the difficulty of resisting impulses—and situational cues. And the approaches can encompass both behavioral strategies—it is sometimes wisest to just walk away from a challenging situation or to call on one’s support network—and cognitive ones, such as distancing oneself from one’s thoughts unil h dure to use dissipates.

Some situations are predictably problematic.

The following situations are among the most common causes of relapse:

• exposure to environmental cue related to drug use

• stress

• interpersonal difficulties

• lack of social support

• pain due to injuries or medical problems

• lack of a sense of self-efficacy

But not all situations linked to relapse are negative. Positive moods can create the danger of relapse, especially among youth. Research identifying relapse patterns in adolescents recovering from addiction shows they are especially vulnerable in social settings when they trying to enhance a positive emotional state. Negative emotions play a larger role in relapse among adults.

Avoidance is an excellent coping strategy if you know that you are likely to run into danger. Of course, that requires understanding what your triggers are. But life is often unpredictable and it’s not always possible to avoid difficulty.

One way of ensuring recovery from addiction is to remember the acronym DEADS, shorthand for an array of skills to deploy when faced with a difficult situation—delay, escape, avoid, distract, and substitute.

• Delay. In the face of a craving, it is possible to outsmart it by negotiating with yourself a delay in use. It hinges on the fact that most cravings are short-lived—10 to 15 minutes—and it’s possible to ride them out rather than capitulate.

• Escape. Getting out of a high-risk situation is sometimes necessary for preserving recovery. It’s possible to predict that some events—parties, other social events—may be problematic. It’s wise to create in advance a plan that can be enacted on the spot—for example, pre-arranging for a friend or family member to pick you up if you text or call.

• Avoid. Some events or experiences can be avoided with a polite excuse.

• Distraction. Distraction is a time-honored way of interrupting unpleasant thoughts of any kind, and particularly valuable for derailing thoughts of using before they reach maximum intensity. One cognitive strategy is to recite a mantra selected and rehearsed in advance. A behavioral strategy is to call and engage in conversation with a friend or other member of your support network.

• Substitute. When an urge to use hits, it can be helpful to engage the brain’s reward pathway in an alternative direction by quickly substituting a thought or activity that’s more beneficial or fun— taking a walk, listening to a favorite piece of music. Possible substitutes can be designated in advance, made readily available, listed in a relapse prevention plan, and swiftly summoned when the need arises.

Attending or resuming attending meetings of some form of mutual support group can be extremely valuable immediately after a lapse or relapse. Discussing the relapse can yield valuable advice on how to continue recovery without succumbing to the counterproductive feelings of shame or self-pity.